What the stories of the Chibok girls and that of the converted suicide bomber point to is the certain defeat of Boko Haram insurgency and the waning resonance of its underpinning ideology. While we had to put troops on the ground to liberate occupied territories and free captive people in the North-East, we would have to continue the battle for the minds of the radicalised many…

In the last seven years, North-Eastern Nigeria has been ravaged by the violent Islamist jihadi group nicknamed Boko Haram. [The name originated from a decree issued by its leader earlier Mohammed Yusuf, that Western education, government schools, (Boko) and working for the Nigerian government are forbidden (Haram)].

It’s real name “Ahl al-Sunna li’l-Da’wa wa’l-J’had’ala Minhaj Al-Salaf” (Association of the people of the Sunna for the missionary call and the armed struggle according to the method of the Salaf), speaks more directly to its ideological provenance. The group broke away from the Ahlus Sunna, a Nigerian group established by graduates of the Islamic University of Medina, who propagated the Wahhabi da’wa (missionary call) against the mainstream scholars and the Sufi orders. [Note that the call of the Ahlus Sunna did not include an armed struggle (Jihad)].

The group operated mainly in and out of Maiduguri, Borno State. Its founder Mohammed Yusuf, who had been a foremost member of Ahlus Sunna in Maiduguri and a preacher of Wahhabi da’wa clearly indicated in the new name of his faction that this was Ahlus Sunna for the missionary call and the armed struggle.

Boko Haram, like other Salafi sects, sees itself as the custodian and successor to the “pious predecessors”, authentic Muslims, who regard foundational Islamic scripture as rigidly applicable today. In keeping with classic Salafi-jihadi tradition, Boko Haram regards most mainstream Muslims and even Sunni leaders as apostates, rejecting the authority of states on the grounds that believers should not be subject to infidel systems.

Boko Haram ideology rests on two constructs.

First, an absolutist theology that rejects every other, including rival Islamic iterations, and the socio-political and value systems that are ostensibly based on them. Thus democracy, the rule of law, constitutionalism, and western education are rejected largely on account of their judeo-Christian origins.

“Democracy”, said Yusuf, “is the school of infidels, following it, having dealings with it or using its system is unbelief.” [quoted in Alex Thurston’s The Disease Is Unbelief: Boko Haram’s Religious and Political Worldview).

Second, a strong notion of victimhood that asserts that true Muslims are and will always be subjected to persecution by the state and its law enforcement apparatus. Both Yusuf and his successor Abubakar Shekau often cite well-known Christian/Muslim riots in Nigeria, and somehow conclude that these evidenced state aggression. Connivance between Christians and the state to oppress Muslims was also alleged and used to justify the bombing of churches, especially in the North-West and North-Central States of Nigeria.

foraminifera

There appears to be scholarly consensus that the militant violent radicalisation of the BH originated from its bloody and often fatal encounters with Nigerian law enforcement at various times. As far back as 2002, a group of youth, associated with the Alhaji Ndimi mosque, the religious centre of Ahlus Sunna in Maiduguri, had established a salafist purist self-governing commune outside the city.

Over the years, it clashed frequently with the police who apparently became aware that the group was amassing arms. The final and fatal clash was in 2004, with the police killing almost all members of the group, including its leader. It would appear that Mohammed Yusuf and other members of the Ahlus Sunna though, not members of this Salafist-jihadist splinter group, embraced its members after the fatal encounter with the police. Yusuf and his group were later to suffer the same fate.

Yusuf had initially collaborated with the government of the North-Eastern state of Borno in its Sharia implementation programme. He later repudiated the programme, arguing that the Sharia could never be faithfully implemented by a non-Islamic government structure. In 2009, after several clashes with the police and the Borno State government, he launched an uprising which spread to four other Northern Nigerian states. Over 1000 people died. Mohammed Yusuf was arrested and killed while in police custody. His extra-judicial killing and the law enforcement brutality which pervaded the handling of the uprising and its aftermath is frequently cited as a milestone in the ultra-violent radicalisation of Boko Haram.

Abubakar Shekau cited the incident as evidence of state brutality: “everyone knows the way in which our leader was killed. Everyone knows the kind of evil assault that was brought against our community. Beyond us, everyone knows the kind of evil that has been brought against the Muslim Community of this country periodically…”

In the aftermath of this uprising, leadership of the BH fell on the hands of Abubakar Shekau who was a long-standing preaching compatriot of Yusuf. It is to Shekau’s leadership that the egregious violence for which BH is notorious is attributed. From 2009, Boko Haram undertook a campaign of brutality. Most of its objectives seemed short term, vengeful, and a reaction to real or perceived hostility, but was in almost every case egregiously brutal.

In 2011, its activities mainly revolved around hunting down Borno State politicians who were perceived as complicit in Governor Modu Sheriff’s alleged betrayal of the sect. Mid-year, it extended its reach to the capital, Abuja, bombing the Nigeria Police Headquarters and the United Nations Headquarters, killing and maiming scores of people in the process.

In the same period, it simultaneously bombed seven police stations and the immigration headquarters in the North-West state of Kano.

On Christmas Day 2011, a coordinated bombing of churches resulted in 41 fatalities. In January 2012, another three churches were attacked on the same day in Kaduna State. 2015 was probably Boko Haram’s year of most brazen infamy. The group, using female suicide bombers, many who were mere children, attacked 28 different religious events, mostly mosques and Islamic gatherings. It was obvious even then that Boko Haram had lost the capacity to sustain military attacks in the way it had previously done. Perhaps to shore up its image it declared its allegiance to ISIS.

Governance

Although former President Goodluck Jonathan’s government escalated its crackdown on Boko Haram from 2011 onwards and declared a State of emergency in the North-East, it neither seemed determined nor focused on routing Boko Haram. Several factors may explain the government’s attitude.

First, a politically convenient narrative of the ruling party was that Boko Haram was actually sponsored by a Northern Muslim political elite determined to discredit the government led by a Christian, and which had its main support base in the predominantly Christian South-South and South-East. When the opposition parties finally came together to form the current ruling party, the APC, the then ruling party’s publicity organ was quick to describe the party as the “janjaweed” party, and worked hard to paint it as the political wing of the Boko Haram.

Indeed it was not until President Muhammadu Buhari, then the presumptive leader of the opposition, was nearly killed in a deadly Boko Haram attack on his car in Kaduna, that the false narrative began to lose credibility.

Second, the ruling party also somewhat cynically seemed to have considered that since BH attacks were actually in the heartland of the opposition, it was not necessarily an unwelcome development as it could only weaken the opposition.

Third, extensive corruption in arms procurement, estimated at about USD15 billion, ensured that the military remained poorly equipped and demoralised. A number of well-publicised mutinies occurred and troops involved were taken through widely unpopular court-martials.

As the government dithered and equivocated, Boko Haram proceeded to realise its objective of occupying territory and establishing Islamist states in Nigeria and in the Lake Chad basin. In Borno State alone it occupied and hoisted its flag in 20 of the 27 local governments that constituted the state. In Adamawa, Boko Haram took Mubi, and also villages in Yobe State.

It was probably not until the abduction of more than 200 secondary school girls from their dormitories in the sleepy, largely Christian town of Chibok that public outrage against the government’s inept handling of the the insurgency reached a crescendo, even on a global scale.

The government of the day then incurred widespread anger when it denied that an abduction had taken place and suggested that the opposition had simply invented the story. As the heart-rending stories of the girls’ parents emerged, the credibility and sincerity of the government became severely questionable.

Boko Haram continued to occupy most of the territories it had seized until two weeks to the general election, when the Federal Government, in a move widely perceived as designed to gain some time within which it may be able to turn the tide in its favour, postponed the elections for six weeks, ostensibly to flush out Boko Haram from the North East.

Although it recorded some successes, Boko Haram’s hold remained largely intact. It’s suicide bombing campaign was stepped up and in the first quarter of 2015 alone, there were several cases of suicide bombings resulting in deaths and maimings.

Enter President Buhari’s Administration

Clearly one of the strongest reasons for President Buhari’s victory in the March 2015 Presidential election was the expectation that going by his reputation as a no-nonsense soldier he would defeat Boko Haram and restore peace to the North-East. He moved quickly to realise this objective, announcing a relocation of the Command and Control Headquarters of the army to Maiduguri, right in the heart of the insurgency. He changed all the military service chiefs, some of who were indicted in the arms procurement scandal.

With more effective leadership, command and control, improved logistics and intelligence, better equipment and motivation of the troops, the tide soon turned. The quick procurement of critical equipment and platforms, prompt payment of allowances and effective welfare greatly improved troop morale. In the fortnight after he was sworn in, he visited the Heads of States of the Lake Chad Basin countries and Benin Republic, all crucial allies in the defeat of Boko Haram. The active cooperation of these countries and the collaboration of several G7 nations, especially in intelligence, significantly impacted the effort.

Within six months, Boko Haram had been effectively dislodged from all the local governments they once held and had retreated into Sambisa Forest and the Northern border towns and villages. Their military capacity had been severely degraded, their supply lines effectively blocked. However, by the very nature of asymmetric warfare, Boko Haram was still able to do some damage and gain some attention by its suicide bombings of markets, mosques, churches and commercial bus parks. It’s ability to find willing suicide bombers remained a mystery, although some of the bombers were mere children who would have had no idea what would happen when they pulled the detonator of the baggage they carried. In the past several months, there has hardly been a single case of suicide bombing.

Costs of the Insurgency and the Humanitarian Crisis

The years of the Boko Haram insurgency have been costly for Nigeria and our neighbours in the Lake Chad basin. Well over 20,000 people have died. There are over 50,000 orphans in Borno State alone. There are close to two million internally displaced persons, some in IDP camps but most in host communities. With the freeing of starved Boko Haram captives in the forests and border villages, fresh problems of severe manultrition in children have emerged.

That most of these agrarian States of the North-East have not been able to farm for years has meant food shortages and deepening poverty on account of joblessness. Many farmlands have been mined by the terrorists. Roads, bridges, power assets, schools, hospitals and other infrastructure have been severely damaged. The challenge today is how to turn this monumentally tragic story around.

First is dealing with the surviving human casualties of the insurgency. Providing adequate food, shelter and medical care for IDPs, educating thousands of out of school children and young people; dealing with radicalised men, women and sometimes children; caring for sexually assaulted women and girls [some of whom have reportedly been abused in IDP camps].

Second is trying to understand the scourge of violent Islamist extremism better, in order to equip ourselves for the future.

The Federal Government and State governments in the North-East, as well as local and foreign development partners have worked extremely hard to handle the huge humanitarian situation in the area. Expectedly, coordination of the numerous efforts has been a problem given the sheer number of humanitarian actors.

Just before I left Nigeria, President Buhari inaugurated the Presidential Committee on North-East Initiatives (PCNI), to coordinate all humanitarian and development interventions in the region. The committee is also meant to coordinate the Buhari Plan.

The Plan is an integrated blueprint that harmonises the various initiatives of the region’s major stakeholders, which include the following:

• The state governments of the North-East, who developed a common framework and strategy to address the crisis – the North East States Transformation Strategy (NESTS);

• The previous administration’s Presidential Initiative for the North East (PINE), which developed the Emergency Assistance, Social Stabilisation, Economic Reconstruction and Redevelopment (EA-ES and ERR) plans to address the humanitarian crisis and reconstruct the region;

• The North East Recovery and Peace Building Assessment (RPBA), which provides collective strategy for peace building and recovery, as well as a framework for coordinated support to the victims of the insurgency in the region. The assessment, which was concluded in March 2016, was led by the Office of the Vice President with the active participation of the six affected states and supported by the World Bank, United Nations and European Union;

• Other assessments and humanitarian response plans by local and international NGOs and donor partners, including the Victims Support Fund (VSF);

The overall objective of the Buhari Plan is to develop a structure and process capable of providing leadership, co-ordination and synergy in achieving its targeted goals, which are to:

• Restore peace, stability and civil authority in the North-East region;

• Co-ordinate the mobilisation of targeted resources to respond to the humanitarian crisis and jumpstart the region’s economies, while strategically repositioning the region for long-term prosperity;

• Provide equal access to basic services and infrastructure;

• Promote a civic culture that integrates zero tolerance to sexual and gender based violence, with peaceful co-existence as the success indicator;

• Accelerate equal access to quality education for girls, as well as boys, and building social cohesion;

• Target social and economic development and capacity building that reduces the inequalities affecting the poor, particularly women and youth;

• Address environmental degradation through sustainable measures to halt desertification and protect the Lake Chad resources;

• Physical reconstruction of infrastructure, especially schools, hospitals and dwellings in areas considered safe for residents to return.

Regarding the treatment of abused women and girls, although the scale of interventions that needs to be made to make a significant impact can sometimes be daunting, the government, in collaboration with local and foreign partners, is establishing special programmes and shelters for abused women and girls. Ultimately we realise that the most important long term therapy is the assurance that the state has the capacity and will to protect the most vulnerable.

Poverty, Governance Failure and Terrorism

In understanding the etiology of Boko Haram and other strains of such violent extreme (Islamist) terrorism, it will be important to interrogate the theory that poverty and governance failures were responsible for the emergence of Boko Haram. There is no question that extreme poverty and illiteracy easily provide a pool of recruitable youth, especially if the pay is attractive. Here, ideological indoctrination may not always be at play. However, while the argument that poverty and governance failures spawned Boko Haram is attractive, it is inadequate.

First, although it is true that prevalence of poverty is much higher in Northern Nigeria than the South, with the North-East faring worse than all other zones, yet Borno State where Boko Haram has its most prominent footprints is one of the more affluent States in the North and places a respectable 19 of 36 states in GDP ranking. The poorest states – Sokoto and Kebbi – both in the North-West and predominantly Muslim North have been free of violent extremist groups.

As for governance issues, there is no question about the correlation. The impunity of the extra-judicial killings of Boko Haram leaders and members, especially between 2004 and 2009, demonstrated grave institutional weakness.

The mind-boggling corruption in arms procurement towards the war against Boko Haram terrorism which inexorably impaired the FGNs ability to bring the insurgency to an end earlier, clearly demonstrates the impact of these failures of governance. But governance failures affected every part of the country and many more than even the North-East without resulting in the birth of a deadly terrorist group.

Since 2013, the Federal Government has been developing a comprehensive strategy to counter violent extremism, coordinated by the Counter Terrorism Centre. The programme has three core streams: the Counter-radicalisation and De-radicalisation programmes, and the Strategic Communication programme.

The De-radicalisation programme is essentially custody-based, catering for convicted terrorists, suspects waiting trial, and aftercare for convicts upon release. The strategic communication platform is designed, inter-alia, to mobilise our history and culture and reaffirmatory narratives to address the identity/intellectual deficit that may in some ways account for the radicalisation of young people.

The notion that Boko Haram ideologues would one day see the light, renounce their ideology and follow the path of peace is unlikely. Rather it is our view that a more realistic objective will be to diminish its attractiveness to potential recruits by presenting counter-narratives that delegitimise violence against Muslims or people of other faiths in order to gain the ascendancy of one set of ideas. So also is the support for and promotion of the ideas and teachings of mainstream Islamic thought leaders, not as apologists for western thought but as forceful advocates of authentic Islamic teachings.

There is no question at all that greater official attention must be paid to human rights observance. The use of excessive force or extra-judicial or unlawful force, fatal or non-fatal, has been the subject of considerable attention by the Buhari government. The correlation between law enforcement brutality and violence by its targets and others under its care is too stark to be ignored. Part of the reason for respect for law enforcement is that they are fair and even-handed keepers of the peace. Crossing the line would almost always lead to a loss of confidence.

The argument is sometimes made that asymetric warfare of the sort deployed by terrorists must be met with lower standards of human rights observance or at worst much more nuanced rules of engagement. The problem, of course, is that any discretionary observance of human rights is a slippery slope that is probably best not undertaken.

The commitment that the Federal Government has made is to be consistent and there is no distrust for the political leadership in Nigeria today, and for good reason, this has promoted the easy embrace of dissenters of all shades by the people. Nigeria has a great opportunity to change the perception of leadership as being corrupt and unreliable, with President Buhari, who is widely acknowledged as being forthright and honest, Mai gaskiya (the truthful one, as he is known in the North).

Transparency in government, social investments, provision of education and healthcare could improve the government’s image as being responsive.

I like to end with two stories: the one courageous, the other joyful, and both hopeful.

You may have heard the story of a teenage girl, Aishat Ali Kaka, in Borno State, Nigeria. About 18 years old, she was recruited alongside other young women to wear a bomb around her waist, and detonate it at an IDP camp in the town of Dikwa. The mission was set for February 9, 2016. She decided that not only would she not carry out the evil assignment, knowing that many including her own father could be killed, but that she would even try to convince the other two potential suicide bombers to abandon the mission. But they refused.

So she decided that she would put her own life on the line, by going to the targeted camp early on the day before the planned bombing, to sound an alarm before the bombers arrived. But by the time she got there, the terrible deed had been done.

The second story. Earlier this month, on Thursday October 13, 2016, my wife, Dolapo and I received and welcomed back to freedom in Abuja, twenty-one (21) of the schoolgirls kidnapped by the Boko Haram insurgents from Chibok over two years ago.

After the trauma and deprivations of captivity, on the day of their release they looked frightened, malnourished and unkempt. But such is the power of freedom that a few days after the release, the girls were seen dancing and rejoicing heartily at a thanksgiving service where their parents reunited with them for the first time in over two years!

What the stories of the Chibok girls and that of the converted suicide bomber point to is the certain defeat of Boko Haram insurgency and the waning resonance of its underpinning ideology. While we had to put troops on the ground to liberate occupied territories and free captive people in the North-East, we would have to continue the battle for the minds of the radicalised many, so that we can have more Aminas of Dikwa saying no to terrorist propositions of death, despair and destruction.

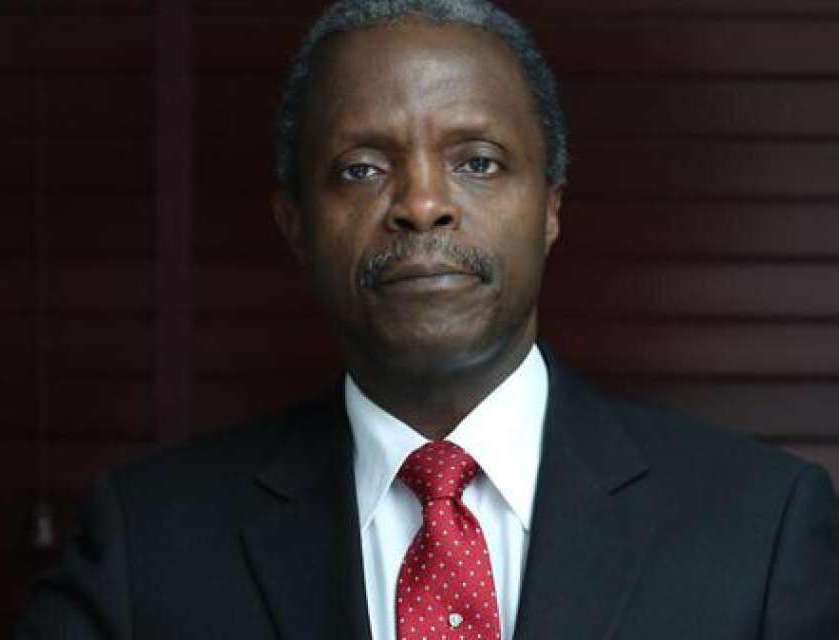

Yemi Osinbajo (GCON), a professor of law and Senior Advocate of Nigeria, is vice president of the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

This is the text of a public lecture delivered at Harvard University’s Weatherhead Center for International Affairs on October 27, 2016.

PremiumTimes

END

Be the first to comment