While the UK and much of the world struggles with overcrowded prisons, the Netherlands has the opposite problem. It is actually short of people to lock up. In the past few years 19 prisons have closed down and more are slated for closure next year. How has this happened – and why do some people think it’s a problem?

The smell of fried onions wafts up the metal staircase, past the cell doors and along the wing. Down in the kitchen inmates are preparing their evening meal. One man, gripping a long serrated blade, is expertly chopping vegetables.

“I’ve had six years to practice so I am getting better!” he says.

It is noisy work because the knife is on a long steel chain attached to the worktop.

“They can’t take that knife with them,” says Jan Roelof van der Spoel, deputy governor of Norgerhaven, a high-security prison in the north-east of the Netherlands. “But they can borrow small kitchen knives if they hand in their passes so we know exactly who has what.”

Some of these men are inside for violent offences and the thought of them walking around with knives might seem alarming. But learning to cook is just one of the ways the prison helps offenders to get back on track after their release.

“If somebody has a drug problem we treat their addiction, if they are aggressive we provide anger management, if they have got money problems we give them debt counselling. So we try to remove whatever it was that caused the crime. The inmate himself or herself must be willing to change but our method has been very effective. Over the last 10 years, our work has improved more and more.”

He adds that some persistent offenders – known in the trade as “revolving-door criminals” – are eventually given two-year sentences and tailor-made rehabilitation programmes. Fewer than 10% then return to prison after their release. In England and Wales, and in the United States, roughly half of those serving short sentences reoffend within two years, and the figure is often higher for young adults.

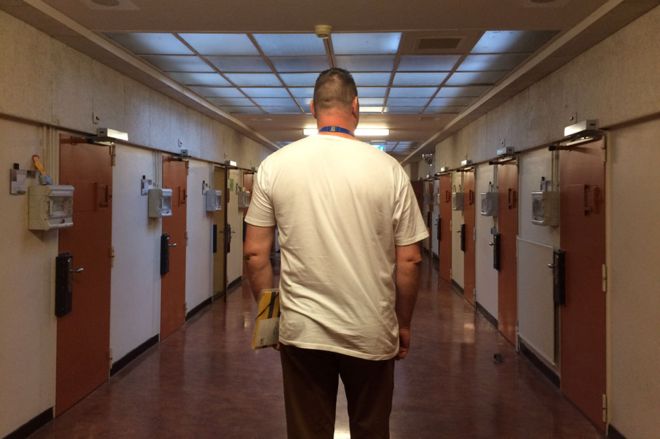

Norgerhaven, along with Esserheem – another almost identical prison in the same village, Veenhuizen – have plenty of open space. Exercise yards the size of four football pitches feature oak trees, picnic tables and volleyball nets. Van der Spoel says the fresh air reduces stress levels for both inmates and staff. Detainees are allowed to walk unaccompanied to the library, to the clinic or to the canteen and this autonomy helps them to adapt to normal life after their sentence.

A decade ago the Netherlands had one of the highest incarceration rates in Europe, but it now claims one of the lowest – 57 people per 100,000 of the population, compared with 148 in England and Wales.

But better rehabilitation is not the only reason for the sharp decline in the Dutch prison population – from 14,468 in 2005 to 8,245 last year – a drop of 43%.

The peak in 2005 was partly due to improved screening at Amsterdam’s Schiphol airport, which resulted in an explosion in the numbers of drug mules caught carrying cocaine.

Today the police have new priorities, according to Pauline Schuyt, a criminal law professor from the southern city of Leiden. “They have shifted their focus away from drugs and now concentrate on fighting human trafficking and terrorism,” she says.

In addition, Dutch judges often use alternatives to prison such as community service orders, fines and electronic tagging of offenders.

Angeline van Dijk, director of the prison service in the Netherlands, says jail is increasingly used for those who are too dangerous to release, or for vulnerable offenders who need the help available inside.

“Sometimes it is better for people to stay in their jobs, stay with their families and do the punishment in another way,” she says from her brightly lit office at the top of a tower block in The Hague.

“We have shorter prison sentences and a decreasing crime rate here in the Netherlands so that is leading to empty cells.”

But while recorded crime has shrunk by 25% over the past eight years, some argue that this results from the closure of police stations, as a result of budget cuts, which makes crime harder to report.

Other critics, such as Madeleine Van Toorenburg – a former prison governor and now the opposition Christian Democratic Appeal party’s spokeswoman on criminal justice – blame the shortage of prisoners on low detection rates.

“The police are overwhelmed and can’t handle their work load,” she says. “And what is the government’s response? Closing prisons. We find that surprising.”

What is clear is that many of Angeline van Dijk’s staff are not happy about the lack of people to lock up.

Frans Carbo, the prison guards’ representative from the FNV union, says his members are “angry and a little bit depressed”.

Young people don’t want to join the prison service he adds “because there is no future in it any more – you never know when your prison will be closed”.

One empty prison was turned into a fancy hotel south of Amsterdam, its four most expensive suites named the The Lawyer, The Judge, The Governor and The Jailer.

But others, converted into asylum reception centres, have provided work for some former prison guards.

The desire to protect prison service jobs has sparked another surprising solution – the import of foreign inmates from Norway and Belgium.

“At one point our state secretary met the Norwegian minister of justice and said I have some cells to spare – you can rent one of our prisons,” says Jan Roelof van der Spoel.

So last September Norway began sending some of its convicts south to serve their sentences at Van der Spoel’s prison, Norgerhaven.

The governor of the prison is now a Norwegian, Karl Hillesland, but the prison guards keeping an eye on the 242 men locked up here are Dutch.

A mild-mannered former bookseller with a bushy moustache, Hillesland strikes me as an unlikely jailer. His green uniform with epaulettes looks extremely formal, and is nothing like the relaxed clothing of his Dutch colleague, but in fact Norway has a more liberal prison regime than the Netherlands, he says. Norwegian inmates are allowed, for example, to give media interviews and watch DVDs of their choice because the underlying principle is one of “normalisation”, meaning that life in prison should replicate life on the outside as closely as possible to help ex-offenders reintegrate into society.

“There are some differences in the way we do things,” says Van der Spoel. “We discipline a prisoner for breaking the rules straight away whereas the Norwegians do an investigation and wait a while before imposing the punishment. For our guards that style of working was a bit tough to begin with.”

“But on the whole”, says Hillesland, “we share the same basic values about how to run a prison.”

He adds that a few prisoners were forced to come here from Norway but most volunteered, partly because groceries and tobacco are cheaper in Holland.

A recently installed Skype room is another big attraction at Norgerhaven. Relatives who want to visit have to pay their own travel costs, and a round trip costs at least 500 euros with an overnight in a hotel. But many of the long-term prisoners are foreign nationals who very rarely saw their families anyway when they were behind bars in Norway.

Michael’s immaculately tidy cell is decorated with pictures of his football team and his four small children. A welder from northern Poland he was convicted in Norway but didn’t have access to Skype in prison there.

“My wife is busy looking after four kids and trying to hold down a job and anyway she doesn’t have the money to come and see me”, he says. “So I opted for this prison so I could see my family and not just hear their voices on the phone.”

He stares at the floor for a moment or two. “After the Skype call it’s very hard – especially at Christmas and Easter but it is better than nothing.”

As I leave through security doors and clanging gates I wonder what will happen to Norgerhaven once the Norwegians have gone in a few years’ time.

The guards know that one of the Veenhuizen jails – Norgerhaven or Esserheem – will be listed for closure next year. But could the numbers of prisoners in the Netherlands ever rise again?

A walk through the village is a reminder that, in the distant past, the Netherlands locked up large numbers of citizens.

It’s located in the remote, sparsely populated Drenthe province – a land of peat bog, fens and heather known as the “Dutch Siberia”, and a place where beggars, tramps, penniless orphans and other “undesirables” were exiled from the cities in the 19th Century.

An army general founded a reform colony in Veenhuizen, which he believed could eradicate poverty. Over time the institution morphed into a penal colony which was closed to outsiders until the 1980s.

According to a demographer, one million of Holland’s 17m citizens alive today are descendants of people exiled to Veenhuizen.

“That’s a huge chunk of the population,” says Amsterdam-based author Suzanna Jansen, whose grandfather was sent there for begging.

“And being raised in poverty, in a difficult environment is something that could happen to any one of us, so I think we should remember that when we think about those behind bars today.”

END

Be the first to comment