So much has been said and written about the Russian invasion of neighbouring Ukraine on 24th February 2022. But unfortunately, the narratives have been largely monolithic and unbalanced, lacking in editorial rigour, investigative journalism and critical interrogation by the mass media on both sides of the conflict.

The world has unashamedly been treated to a cocktail of lies, fake news, propaganda and unethical reportage by Russia’s mainly state-controlled media and a disappointing so-called liberal Western media.

Reputable journalism schools teach and place a high premium on professional code of ethics, including the responsibility by professionals to expose government interference, censorship and how safeguard objectivity principles. Objectivity itself can be tricky, possibly resulting in being “subjectively objective.” Even so, it remains an ideal and a goal worth pursuing.

The mainstream media have conveniently christened the Russia-Ukraine conflict as a “war,” but most known theories and concepts of media professional ethics on war/conflict reporting have either redefined or jettisoned. As happened with the COVID-19 pandemic, where politics has hijacked science and scientists’ narratives, politicians have seized the initiative and controlled the media over what is being dished out as news on the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

The invasion of a sovereign nation by another is not only against international laws and instrumentality but is always condemnable. So, Russia is wrong to have invaded Ukraine as it was in annexing the Crimean Peninsula from Ukraine in 2014.

But that is only part of the story. The Russian Federation and Ukraine both belonged to the former Soviet Union, which was dissolved in 1991. Russians and Ukrainians are cousins, with families on both sides. There are two pro-Russia Donnas and Donetsk regions in Ukraine and some 17.3% are Russian-speaking Ukrainians.

However, while most of the former Soviet Union States have joined Western Europe, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), Russia stands alone, operating a hybrid governance system of communism and capitalism.

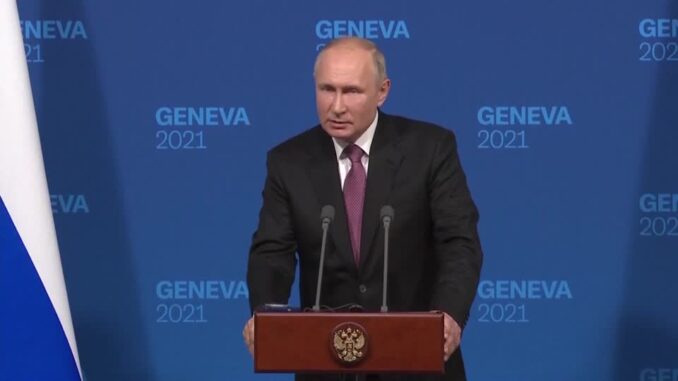

Since assuming the leadership of Russia, Vladimir Putin, a former KGB foreign intelligence officer, has made no secret of his agenda to retain the former Soviet hegemony.

Having served briefly as Director of the Federal Security Service (FSB) and later Secretary of the Security Council, Putin was appointed as Prime Minister in 1999 under former President Boris Yeltsin. Following Yeltsin’s resignation, Putin became acting president, and less than four months later, he was elected to his first term as President. He was re-elected in 2004 for the second term limit but came back as Prime Minister from 2008 to 2012 under President Dmitry Medvedev.

Putin returned to the presidency in 2012 and was re-elected again in 2018. In 2021, he signed into law constitutional amendments following a referendum, including one that would allow him to run for re-election twice more, potentially extending his presidency to 2036.

These were all within Putin’s rights under his country’s constitution, but in international geopolitics and under the ruthless economic rivalry among the superpowers, there has been no love lost between Putin’s Russia and Western Europe even after the Cold War.

As a nuclear power, Russia retains its veto power status at the United Nations Security Council and remains opposed to NATO presence near its doorsteps (in Ukraine), just like America, the unelected leader and defender of the liberal capitalist world cannot allow any rival power around its neighbourhood or sphere of influence.

Despite signing a European Union-Ukraine Association Agreement, Ukraine’s 5th President, Petro Poroshenko, an Oligarch with several business interests, did little to stop the Russian annexation of Crimea. He served for only one term and lost the presidency in 2019 to incumbent President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, 44, a lawyer-cum actor, comedian and then a largely unknown political figure.

Putin, by invading Ukraine, might have played into the hands of his American and European “enemies.” On the other hand, showman Zelensky, in trying to make political capital out of the invasion, has plunged his country into a dangerous war. While troops are fighting and dying on the battlefield, he has continued his tour of world capitals to drum up military and economic support against Russia.

The February 24 incident is not the first invasion in modern history. The U.S. has invaded Iraq and Afghanistan and joined NATO to invade Libya, resulting in regime changes, war crimes, humanitarian disasters, deaths of thousands of people, displacement of millions of others, and destruction of properties worth billions of dollars.

At issue in the Russia-Ukraine conflict is Ukraine’s plan since 2019 to join NATO to boost its military capability in the face of Russian aggression. As expected, Moscow is vehemently opposed to this plan and continues to deny Western allegations that Russia wants to influence Ukraine, insisting that its main desire is for Ukraine to be neutral, a buffer State, and out of NATO.

More than one month into the invasion, Ukraine is no longer insisting on NATO membership and has not ruled out talks about the country’s possible neutrality in negotiations with Russia. Under international law, neutrality refers to the obligation by a State, through a unilateral declaration or coercion, not to interfere in military conflicts of third States. Examples are Switzerland, Ireland, Sweden, Finland and Austria, with the last four still members of the European Union.

But what has been the role of the mass media as the Fourth Estate of the Realm, the guardian of the people’s rights, liberty and freedom and the public watchdog on the Russia-Ukraine conflict? The Fourth Estate concept, made famous by British Statesman Edmund Burke in the 18th century and echoed by 19th Century historian, Thomas ‘Chuckles’ Carlyle, has been embraced by contemporary scholars who ascribe to journalists, the “fourth power” to check and counterbalance the three State “powers” – executive, legislature and judiciary.

To be continued tomorrow

Ejime is a global affairs analyst, a former war correspondent and an independent consultant on Corporate Strategic Communications, Peace & Security and Elections.

END

Be the first to comment