…questions about an individual’s knowledge on economic policies should play crucial roles in peoples’ choices. Voters and viewers should be able to fact-check claims and be given a window to what the “leader” can do to help navigate the economy in the right direction and create more opportunities for growth amongst other pressing issues.

Monday’s 90-minute, one-on-one record breaking debate between Democrat Hillary Clinton and Republican Donald Trump has, in a fundamental sense, provided a sense of direction to the pile of undecided voters in America. They went to bed knowing who they may likely vote for as president come Tuesday November 8, 2016. What we witnessed on stage that night at Hofstra University in New York was not just a debate between two presidential candidates. It was a modern day American political battle between “The Party of liberals” and “The Party of family values” for perennial advantages in the struggle for the Oval office.

As nothing is perfect in human affairs, the American system is not without its flaws. I believe their democracy is more functional than perfect. But it takes one thing serious: holds its leaders and pubic office holders accountable.

In their campaigns, contestants have to strongly establish that they would be a responsible arbitrating buffer between the citizens and the state. Pundits who endorsed poorly performing office holders who are seeking reelection are called to answer why they surrendered their integrity and fooled people with their partisan appraisals.

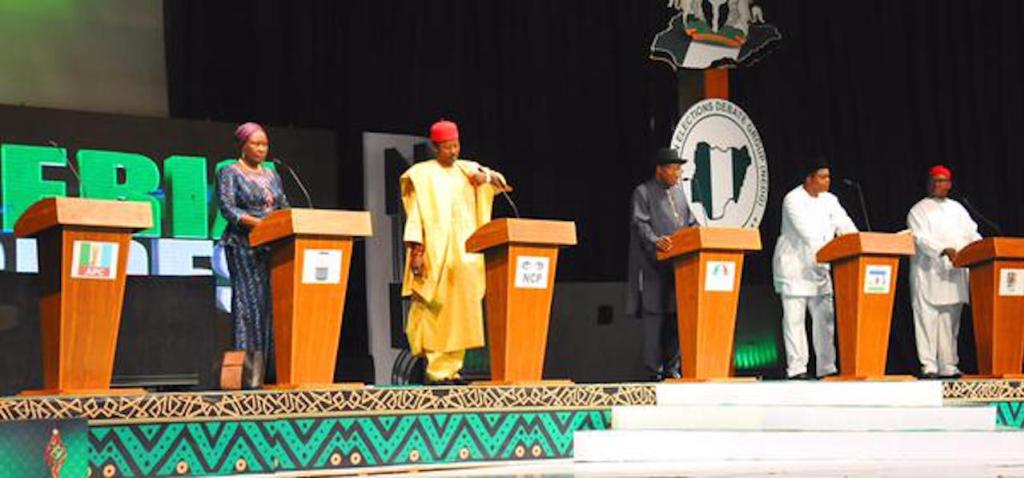

On another note, the debate is a reminder of the interesting social and political culture in Nigeria.

We, Nigerians, created our constitution and laws, and established rules and regulations guiding its operational processes, and its relationships to citizens and institutions. But then, our democratic process, since independence, has not engaged this operational processes effectually. Instead it has, over the years, been plagued by an abysmal level of egoism in an eristic game of perversion.

Truth is our democratic process is, without doubt, a mirror of our culture and a product of our institutions. It is as a system that has become unresponsive to the cry of the citizens, while catering for the ruling class of the country.

For instance, employment is based on who you know rather than what you know. Political positions are largely occupied and controlled by the ruling class with money bags and what Fela, the late Afrobeat king, calls “arrangee masters”. In electioneering times, citizens are manipulated instead of won over in interactive forums such as debates and Town Hall meetings. Young people confusedly join braying campaign crowds into acting out scripts handed out to them by their sponsors in a ricochet manner, as against being more idealistic in their choices and less loyal to acrimonious traditions like their co-equals in the politics of active citizenry in established democracies.

With such emphasis on money and power, it is of no surprise that politics, in Nigeria, is seen by a considerable size of the population as ‘the’ trajectory that shortens the road to wealth.

In any case, it is important to realise that if power becomes institutionalised or routinised by a few in a democratic society, the sinews of citizenship participation either gradually diminishes, simply exists in theory or basically becomes extinct.

Making promises is, generally, an established hallmark in politics. But as repeatedly noted, politicians in Nigeria perceptively over-promise but completely under-deliver because there is no immediate penalty for doing so. Debates are a good place for the public to hear from such public servants about why they failed. Yet many never take the stage.

In the first place, it is unfair for any public office seeking person to ignore an organised debate or town hall meeting. In the words of Pope Francis, “Every man, every woman who has to take up the service of government, must ask themselves two questions: ‘Do I love my people in order to serve them better? Am I humble and do I listen to everybody, to diverse opinions in order to choose the best path?’ If you don’t ask those questions, your governance will not be good.” Debates are organised, so candidates can reveal to the public what they stand for through what they say and how they say it.

Huge campaign rallies, posters, expensive advertising and social media strategies are okay. Nevertheless, they should not be enough reasons to vote for an office seeker. In fact, questions about an individual’s knowledge on economic policies should play crucial roles in peoples’ choices. Voters and viewers should be able to fact-check claims and be given a window to what the “leader” can do to help navigate the economy in the right direction and create more opportunities for growth amongst other pressing issues.

However, some Nigerians care less who gets elected while others would rather see the economy crumble and the country thrown into turmoil under an unqualified candidate, rather than take the chance that it may succeed under a more qualified person simply because of differences in ethnicity or religion.

As we struggle with the thorny challenge of restructuring our economy, we may not bother now about elections. But we should reflect on the repeated abuse of our democratic institutions by a privileged few, especially as it concerns the future of our democracy.

In conclusion, I encourage ethical Nigerians not to give up on building common ground in the pursuit of a generation with political clairvoyance needed to engender a people-based and people-focused system free from vestiges of a shoddy political venture, from which we have had to vote out.

David Dimas, a author, blogger and inspirational speaker, writes from Laurel, Maryland, U.S.A. Email: ddimas01@yahoo.com; Twitter: @dimas4real.

END

Be the first to comment