Across the economy, ripe, low-hanging fruits like these abound. Our task is to find a government that can spot them, and knows what to do with them. In a sense, this may be the only question that the electorate may have to answer in 2019!

There is scant doubt that in the two years that it has been in office, the Buhari administration has struggled to make sense of its mandate. Well, that’s putting the problem mildly. By failing to stop rising unemployment and falling domestic output, it is fair to describe the government as having dropped the main balls in its mandate. Against the backdrop of rising domestic debt, one can only charge it further with building up huge vulnerabilities for tomorrow’s managers of the economy, without putting much in place with which the future may deal with these additional problems.

And basic problems there are aplenty. Even with the best policy mix in place, the loss of domestic capacity to the 2016 recession will require the expenditure of considerable resources to recover from. Failure to support investment in physical infrastructure will mean rising domestic costs into the medium-term; at a time when all efforts should be focused on improving domestic competitiveness. Far costlier, in the long-run, would be the toll that abysmal healthcare and education systems would take on labour productivity. This would be felt both in the inability of successive generations to hold unit labour costs down, and the difficulty the economy would experience making the transition through to digitisation. Of course, the way in which these economic challenges will be lent social expressions will be no less crucial. And it is fair to argue that the process of sublimation is unlikely to be pleasant. Nor the outcome positive for our social fabric.

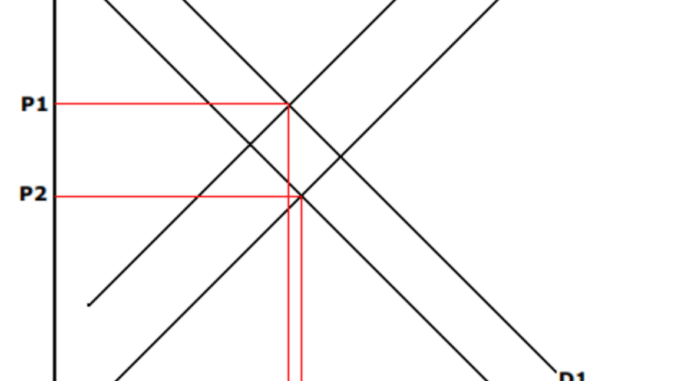

How did we reach this pass? There are as many answers to this question as there are Nigerians with an opinion. Usefully, just about every Nigerian you talk to on this question has a sense of what has to be done to shift the country’s supply curve to the right — for that is what we must do, if we are to fix the myriad woes of this economy. Build better roads. Improve the railway network, so more communities are covered, and the trains run at a faster clip. Improve electricity supply across the country. Improve policing and the speed and fairness with which the courts deal with litigations. Improve school curricula, and the number of years the average Nigerian spends in education and training. Improve healthcare delivery, with focus on tertiary and primary healthcare.

This list could go on. But the basic point in this reform portmanteau is to push domestic cost of doing business down, so that more goods and services can be produced at lower prices.

Unfortunately, a dearth of data on the economy makes this challenge that much worse. What are the school age populations — primary, secondary, and tertiary? What’s the gender distribution of these populations? What is the labour dependency ratio, i.e. how many elderly persons out of work does each worker support? What is the average family size? And how much must each such family earn to be categorised as “poor”, “middle class” or “rich”? How are these numbers distributed across our sub-national spaces? And what is the population balance in these buckets across “urban” and “rural” communities?

…thankfully, for any government that is minded to apply itself seriously to these and allied matters, there are walk-arounds. From the banks, through the telecommunications companies, to the Federal Road Safety Commission (FRSC), biometric and demographic data for just about every 18-year old Nigerian is available…

In the absence of clear answers to these and related questions, the policy formulation process will be a chancy affair. Ultimately, bridges and roads will be built to nowhere, at great expense to the exchequer. Schools will be built in communities where rural-urban migratory practices have denudated the school age population. Etc.

While the data challenge may be important, the process of getting past it is far from onerous. A slew of technological innovations has made it a lot easier to aggregate the required numbers. Our problem is the quality of our response functions. Take national identity management, for example. We have been at this task for decades. India, on the other hand, has built the infrastructure around its 12-digit unique-identity number (Aadhaar) over the last eight years.

Yet for us, thankfully, for any government that is minded to apply itself seriously to these and allied matters, there are walk-arounds. From the banks, through the telecommunications companies, to the Federal Road Safety Commission (FRSC), biometric and demographic data for just about every 18-year old Nigerian is available in some database somewhere in the country.

Privacy and data protection concerns, notwithstanding, I do believe that the algorithms to make these diverse databases interoperable cannot be that difficult to write. Who should pay for connecting the data spots and ensuring that they are searchable? Government, of course. Imagine how much police work could be improved, for instance, if an intelligent police system with the necessary forensic competence had access to the database of fingerprints for Nigerians, 18-years old and above? The ability to match persons to crime locations will obviate the current need for punitive information-extraction procedures.

Across the economy, ripe, low-hanging fruits like these abound. Our task is to find a government that can spot them, and knows what to do with them. In a sense, this may be the only question that the electorate may have to answer in 2019!

Uddin Ifeanyi, journalist manqué and retired civil servant, can be reached @IfeanyiUddin.

END

Be the first to comment