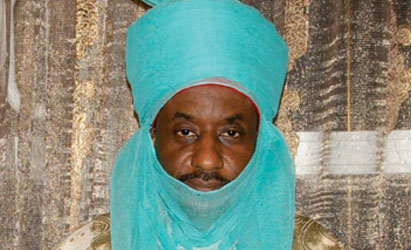

Although so much has been said and written about the dethronement of the controversial erstwhile Emir of Kano, Muhammed Sanusi II, the simmering aftershocks of that deposition are instructive in understanding the tension between traditional institutions and the political dynamics of modernity. Besides, the unfortunate event is laden with invaluable lessons for constructive leadership.

Indeed the gravity of Nigeria’s political space was jolted by the dethronement and subsequent banishment of Emir Sanusi II. The human rights community was awakened from its somnolent state. Legal experts have spewed various interpretations of the constitutions. And it seemed like Kano and Abuja would erupt. Reputed for capitalising on media attention to express his frank opinions, Sanusi was criticised by the establishment for reckless management of emirate funds and disobedience to constituted authorities. For royal blood, an erudite economist and Islamic scholar who also had loosely frolicked in the cosmopolitan ambience of western culture, such accusations would lead to costly crisis. And before long they would bring about his royal end. Neither Kano nor Abuja erupted, and rest is history.

Notwithstanding, there are matters arising from what may be called the Kano Royal crisis. Beyond the media feast on the dethronement and its aftermath, what lessons can Nigerians learn? As has been observed in recent political history, the Kano Royal crisis expresses the apparent polarities between traditional institutions and the modern society within the context of social change. By virtue of their structure, administration and protocol for human relations, traditional institutions are often viewed as normatively conservative, static, and authoritarian. On the other hand, the modern social system bequeathed to Nigeria by colonial administration privileges a civil society built upon the supreme political power of the modern state, which oversees traditional institutions. Meaning that at any given time the state enjoys the monopoly of power over the traditional institution.

As it applies to the deposed Sanusi or any other traditional ruler, no royal father can assume political authority over the organ of state that provided the platform for the exercise of such authority. As a matter of fact, the constitution states that the traditional ruler is an official of the local government. The law says the local government must be able to account for the traditional ruler. The lesson here is this: once a person accepts the post or takes on the responsibilities of a traditional chieftain, however, urbane or aristocratic he or she is, such a person must comply with the constitutional provisions and responsibility of that position.

Second, the crisis has also demonstrated that a traditional ruler or royal father may not be an activist or an opposition demagogue in a most grandiloquent fashion. One of the transcendental attributes of existence is change. Everything in existence undergoes change. Societies and institutions change. And this change often times comes through powerful, charismatic personalities. The charismatic Sanusi, under the garb of royalty, was convinced he could change the society. To effect this change, which he was sure must come from within, Sanusi took and the Fulani aristocracy of which he is part, and lampooned cultural practices that he believed were inimical to progress. He drummed home this point by descending on the Abdullahi Ganduje-led Kano State government, under whose administration his royal stool as Emir stood, and attacked the state policies. He often castigated the federal government and its economic policies.

However, that decision to continuously upset the status quo, through the periodic display of demagoguery, was an imprudent expedition given his royal status. Forces that change the status quo are usually from outside. If they are from within they make themselves renegades of sort. One cannot effectively bring about change and still retain the structure he sought to initially topple. This calls to question the enigmatic, if not inconsistent personality of the dethroned Emir.

It is undeniable that Sanusi Lamido Sanusi courts controversy. Events have shown that his sophistic erudition and cosmopolitan verve are expressly ignited in the public space. Immersed in the euphoria of that space, Sanusi, like the Sophists of Ancient Greece, takes on his adversaries and, by sheer articulation and rhetorical powers, exposes the obnoxious nature of lopsided state policies.

Another lesson from the crisis is that, when the message is separated from the messenger, the prophetic voice of Sanusi has some inescapably bitter truths for the polity. Yet despite the seeming inconsistency between the effervescent personality of Sanusi and the incontrovertible truth of his social crusading, his regular pelting of the establishment and northern political elite has positively affected the Kano citizenry. Without hesitation, one of the targets of his criticisms, Governor Ganduje has banned street-trading and outlawed the notorious Al Majiri system of Islamic and Quranic education. Also in the works are moves to revisit the age-long practice of child-marriage prevalent in the north. This is praiseworthy for the very educated governor.

The message here is that any influential, powerful and privileged activist who is desirous of effecting change, must do so on the altar of self-denial, sacrifice and humiliation. When everyone thought Kano would boil at the dethronement and banishment of Sanusi, Kano kept going on as rustic and traditional as always. Like the local popular Algeria resistant army leader, who was forsaken by the same people he sacrificed his life for, the king who wants to continue his reactionary social crusading must like Sanusi be ready to face the indifference and even criticism of those on whose behalf he fights.

These lessons are relevant for constructive leadership in a modern democracy. Traditional institutions and the actors of the modern state need not play out the polarities pundits have identified. Through some dialectical process of engagement, both can turn polarities into avenues for the reconstruction of the African state. With development and progress in mind, traditional institutions could support genuine social change by constructively presenting history, culture and social context as resources for interrogation. In this way, both provide a platform for an all-inclusive political participation system and process that draw together social forces as bedrocks of the democratization process.

END

Be the first to comment