As the Egyptian plane descended on the tarmac of Beirut Airport on 1 September, 2018, many thoughts filled my heart, how was Lebanon? What manner of country was it? Are the people friendly? The only thing that overwhelmed me back in Nigeria was that the country was home to the dreaded Hezbollah that held the small nation in the jugular some few years back and a deadly civil war. These thoughts and many more clouded my being. I was rudely shaken out of my vanity when the plane hit and taxied on the tarmac. We are in Lebanon!

A group of 10 lucky Nigerians comprising journalists, administrators, student, lecturer and the rest had been selected to embark on a 12-day trip in Lebanon under the Study Abroad in Lebanon, SAIL project. The SAIL Project is a programme of the Notre Dame University, NDU’s Benedict XVI Endowed Chair of Religious, Cultural, and Philosophical Studies in collaboration with the Cedars Institute and the Wole Soyinka Foundation in Nigeria. This course is co-taught by 3–6 faculties with different specializations: Philosophy, Theology, World and Ottoman History, and Art and Architectural History. It is an intensive ten-day course with over eight hours of daily contact and interaction with the faculty, guest lecturers, and officially certified tourist guides.

The distinguishing feature of this course was that it combined and fused rigorous academic knowledge with first-hand experience of historical sites of global and regional significance. It focused on the historical foundation of Lebanon as a geopolitical strategic region that set the stage for the rise of Phoenician Civilization and examined its emergence as a hub of international trade of global significance. The course also showed how Lebanon became a centre of trans-national culture and learning, a refuge for religious minorities, as well as a major region of religious pilgrimage, among others.

The course was structured to enable participants assess and evaluate historical and philosophical concepts both methodically and critically; reflect, think critically about their own experiences confronting new cultural contexts, as well as give participants ample opportunities to engage the faculty in critical discussions of all aspects of the course, and several others.

Participants of SAIL project in Lebanon

While we were yet to settle down at NDU campus, Prof. Edward Alam, a Professor of History at NDU knocked at our doors, saying it was time for business. We had thought we would have a day off, but how wrong were we. Introducing himself warmly, we got down to business. Alam introduced his research assistance, Honoree Claris Eid to us; from then, we knew we were in for a rigorous, but exciting days in Lebanon. The agenda was set, no much time for chatting, browsing and feasting ourselves on the allures of life in Lebanon.

Tony Nasrallah, Assistant Professor of Philosophy, NDU set the stage with his introductory lecture: “Regional History in the Context of World History: The Stellae of Nahr el Kalb.” The stellae were a group of over 20 inscriptions carved into the limestone rocks around the estuary of the Nahr el Kalb (Dog River) in Lebanon, just north of Beirut. The Nahr el Kalb stellae included three Egyptian hieroglyphic stellae from Pharaohs, including Ramesses II, six Cuneiform inscriptions from Neo Assyrian and Neo Babylonian kings, including Esarhadon and Nebuchadnezzar, Roman and Greek inscriptions; Arabic inscriptions from the Mamluk Sultan Barquq and the Druze prince Fakhr el Din II, a memorial to Napoleon III’s 1860 intervention in Lebanon and a dedication to the 1943 independence of Lebanon from France. There were also the stellae of Marcus Aurelius, Proclus, the crusades, among others.

A major wonder in Lebanon was the Jeita Grotto. The grotto represented the pearl of nature in Lebanon. This jewel of tourism was located in the valley of Nahr el Kalb at 18km North of Beirut. The Jeita Grotto was a system of two separate, but interconnected, karstic limestone caves spanning an overall length of nearly 9km. A ride on Cable Car took us to the upper part of the grotto. Historically, the grotto was inhabited in prehistoric times; the lower cave was not rediscovered until 1836 by Reverend William Thomson; it could only be visited by boat since it channelled an underground river that provided fresh drinking water to more than a million Lebanese.

In 1958, Lebanese speleologists discovered the upper galleries 60 metres (200 ft) above the lower cave which had been accommodated with an access tunnel and a series of walkways to enable tourists safe access without disturbing the natural landscape. The upper galleries housed the world’s largest known stalactite. The galleries were composed of a series of chambers, the largest of which peaked at a height of 12 metres (39 ft). Aside from being a Lebanese national symbol and a top tourist destination, the Jeita Grotto played an important social, economic and cultural role in the country. It was one of top 14 finalists in the New 7 Wonders of Nature competition.

At Byblos, A UNESCO World Heritage Site, Dr. Joseph Rahme, Associate Professor, NDU and President of the Cedars Institute, took charge of a lecture: “What is the ‘Lebanon’? What is the ‘Middle East’? Why is it Important? What Role Did Geography play in the rise of Phoenician Civilization? What Kind of continuity exists between the Phoenician past and Contemporary Lebanon? The Phoenician Template: Political Decentralization, Commercial Competition, Social and Religious Diversity.”

In the words of Rahme, the name ‘Lebanon’ was derived from three things-whiteness (snow), mountain and Cedar trees. Lebanon is a sovereign state in Western Asia. It is bordered by Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus is west across the Mediterranean Sea. The earliest evidence of civilization in Lebanon dated back more than seven thousand years, predating recorded history. Lebanon was the home of the Canaanites/Phoenicians and their kingdoms, a maritime culture that flourished for over a thousand years (1550–539 BC). In 64 BC, the region came under the rule of the Roman Empire, and eventually became one of the Empire’s leading centres of Christianity.

In the Mount Lebanon ranged a monastic tradition known as the Maronite Church was established. As the Arab Muslims conquered the region, the Maronites held onto their religion and identity. However, a new religious group, the Druze, established themselves in Mount Lebanon as well, generating a religious divide that had lasted for centuries. During the Crusades, the Maronites re-established contact with the Roman Catholic Church and asserted their communion with Rome. The ties they established with the Latins had influenced the region into the modern era. The region eventually was ruled by the Ottoman Empire from 1516 to 1918. Following the collapse of the empire after World War I, the five provinces that constituted modern Lebanon came under the French Mandate of Lebanon.

One of the stellaes in Lebanon

The French expanded the borders of the Mount Lebanon Governorate, which was mostly populated by Maronites and Druze, to include more Muslims. Lebanon gained independence in 1943, establishing confessionalism, a unique, Consociationalism-type of political system with a power-sharing mechanism based on religious communities. Foreign troops withdrew completely from Lebanon on 31 December 1946.

In Rahme’s view, certain factors gave rise to civilization, which included economic surplus, trading; developing a medium for preservation, accumulation and dissemination of knowledge; development of cities and development of complex, social, economic and political organisation. He explained that the Cedar tree was a symbol of civilization for the Phoenicians which King Solomon used in building the temple in Jerusalem. The Phoenicians were also known for inventing their own alphabetical system which aided the dissemination of information. They established trading outpost through the Mediterranean where they were able to disseminate knowledge in West Mediterranean. In Rahme’ assertion, we didn’t come to Lebanon to know about its history, but discuss world history in Lebanon’s point of view, a replica of what Samuel P. Huntington called ‘Clash of Civilisation.” Lebanon had been a melting point of cultures and civilization, being used and dumped by several foreign invaders, leaving their footprints in the sand of time.

A walking tour of the old city of Byblos, led by historian, Hyame El-khoury revealed it ruins. The castle was built by the Crusaders in the 12th century from indigenous limestone and the remains of Roman structures. The finished structure was surrounded by a moat. It belonged to the Genoese Embriaco family, whose members were the Lords of Gibelet.

Byblos Castle in Lebanon

Saladin captured the town and castle in 1188 and partially dismantled the walls in 1190. Later, the Crusaders recaptured Byblos and rebuilt the fortifications of the castle in 1197. In 1369, the castle had to fend off an attack from Cypriot vessels from Famagusta. The Byblos Castle had distinguished historical buildings for neighbours. Nearby stand a few Egyptian temples, the Phoenician royal necropolis and the Roman amphitheatre. The fortress of the Byblos Castle was later built by the French crusaders spanning 900 years.

Up the Cedars

The pride of Lebanon had always been its Cedar trees dating back to thousands of years. The Cedar is a national symbol in the ancient city. With deforestation and other man-made intrusion, the Cedar of Lebanon is gradually going into extinction, but a portion of the trees have been preserved for tourism purposes. The Cedar of Lebanon is a species of cedar native to the mountains of the Eastern Mediterranean basin. It is an evergreen conifer that can reach 40 m (130 ft) in height. It is the national emblem of Lebanon and is widely used as an ornamental tree in parks and gardens.

The Lebanon cedar once thrived across Mount Lebanon in ancient times. Their timber was exploited by the Phoenicians, Israelites, Egyptians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Romans, and Turks. The wood was prized by Egyptians for shipbuilding; the Ottoman Empire used the cedars in railway construction, among others.

Parking our loads, we left the NDU campus where we were camped and up we go to the Cedars in the mountains of Lebanon. The drive to the Cedars took about two hours. We were to spend three days on altitude where the temperature hovers between 10 and 15 degrees at night. The beauty of Lebanon is revealed by its landscape. Deep valleys and rocky terrains adorn the ambience. In the valleys and mountains, disperse settlements abut the terrains. Shortly after we lodged at the Cedar Institute, off we go to the Cedars. Rahme led the excited Nigerian adventurers to see the Cedars. The Cedar trees are named according to their sizes and circumference. Thus we have biggest Cedar tree named ‘Pope,’ next in hierarchy is the ‘Patriarch,’ followed by the ‘Priest,’ ‘Deacon’ and ‘lay people.’

Rahme listed seven notable things to remember about the Cedars. The first thing was that Queen Victoria built a wall around the Cedars for protection; the trees influenced the nation’s flag, currency and postal stamp; ranking of the trees according to their size; the sculpture of Rudy Rahme depicting the passion of Christ; two helmets in the Cedars; Church of the Cedar Growth built in the 19 century and the ‘Pope,’ which is the biggest tree.

According to Rahme, by the time the Romans intruded the Cedar, there was little Cedar trees left because of deforestation. “The Phoenicians had to rely on triangular trade. The Lebanese are excellent traders. Selling second hand cars is key here,” Rahme said.

A Cedar tree in Lebanon

Clash of interest in Lebanon has made it impossible to conduct a national census, with the last census dating back to 1932. Lebanon has been described as a nation of refuge. Diversity has been the characteristics of Lebanon, with electricity a major challenge like Nigeria.

A tour of the Baalbec, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, reveals the ruin of the temples at Baalbec. A tourist guard said 60,000 slaves worked to build the temples tt Baalbec, which were later destroyed. One of the temples still standing in Baalbec was Bacchus Temple, known as the god of pleasure. The tourist guard said about 100 men and women simultaneously, in nudity feast on the vanity and thrills of life culminating in orgasm. It was a temple of unabated pleasure and defilement.

Visited in the mountains is the Monastery of Saint Antony where Prof. Alam delivered a lecture on “The Global Significance of Christian Monasticism” at the Valley of Qadisha (Holy Valley). Alam delved into what gave birth to Monasticism and its rise. Saint Antony the Great from Egypt is credited as the founder of Monasticism.

Rahme led the tour on the Monastery, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The first printing press in the Arab World dating back to 1610 is at the Monastery Museum. A grotto hewn in the rock at the Monastery serves as refuge abode from invaders. In the cave were artifacts representing faith, refuge and healing. A staff dating back to 13 Century is preserved at the museum, among several others. A tour to the Gilbran Khalil Museum reveals lots of his paintings depicting nudity, but representing the beauty and originally of nature. Khalil was a Lebanese-American writer, poet, visual artist and Syrian nationalist. As a young man Gibran emigrated with his family to the United States, where he studied art and began his literary career, writing in both English and Arabic. In the Arab world, Gibran is regarded as a literary and political rebel. His romantic style was at the heart of a renaissance in modern Arabic literature, especially prose poetry, breaking away from the classical school. In Lebanon, he is still celebrated as a literary hero. His publications were also on display at the museum, the most popular of them being “The Prophet,” one of the bestselling books in the world in the last century.

Ruins of he temples at Baalbec

At the Gilbran Museum, Alam delivered a lecture on the Crusades and how Constantinople was conquered by the Turks. The capture of the city marked the end of the Byzantine Empire, a continuation of the Roman Empire, an imperial state dating to 27 BC, which had lasted for nearly 1,500 years. The conquest of Constantinople in 1453 also dealt a massive blow to Christendom, as the Muslim Ottoman armies thereafter were left unchecked to advance into Europe without an adversary to their rear. The Ottomans ultimately prevailed due to the use of gunpowder (which powered formidable cannons).

Down the Cedars

After three days in the mountains, we were back to the lowland again. The first place of call was Mizyara Village. The village is a display of Lebanese-Nigerian cultural relations. Mizyara is home to many Lebanese who have made their fortune in Nigeria. Example of such is Gilbert Ramez Chagoury, a Nigerian billionaire businessman. Most of the Lebanese in Nigeria erected mansions and develop the village, but do not live in the mansions. They come once in a while. A mansion, with the shape of a plane is built at Mizyara. At Mizyara, there is Abuja Street, Nigeria road, Lagos Street and the rest. The houses in the town bare resemblance of the mansions in Banana Island, Lekki Phase I and the rest. Mizyara is the wealthiest village in Lebanon.

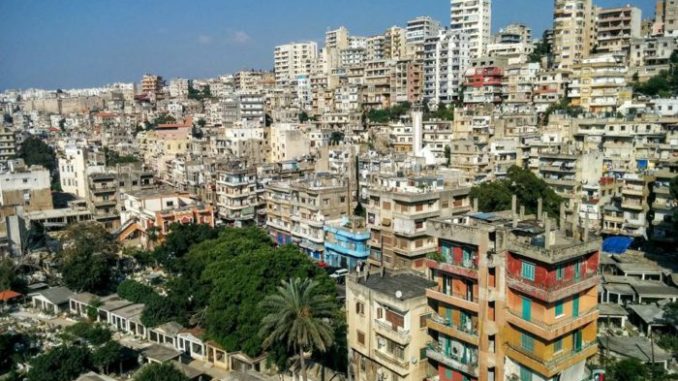

Next point of call was Tripoli (not the Libyan capital). In Tripoli is the ancient Citadel. History has it that in 1102, Raymond VI of Saint Gilles, Count of Toulouse, one of the first knights who set out on the First Crusade in 1096, turned his attention to the conquest of Tripoli, the most important emirate on the coast. Raymond wished to establish a principality that would command both the coast road and the Orontes. In 1103 Saint-Gilles who had camped on the outskirts of the city, ordered the construction of a fortress which to this day is still known by his name. This fortress was the first ever of its kind. No caravan could reach or leave Tripoli without being intercepted by Saint-Gilles’s men.

During the Crusade period, Tripoli witnessed the growth of the inland settlement surrounding the “Pilgrim’s Mountain” (the citadel) into a built-up suburb including the main religious monuments of the city such as: The “Church of the Holy Sepulchre of Pilgrim’s Mountain”, the Church of Saint Mary’s of the Tower, and the Carmelite Church. The state was a major base of operations for the military order of the Knights Hospitaller, who occupied the famous castle Krak Des Chevaliers.

In 1289, when the Mamluk occupied the city, the Mont Pèlerin quarter was set ablaze, the castle of Saint-Gilles suffered from the holocaust and stood abandoned on the hilltop for the next eighteen years. But, in 1308, The Mamluk Governor Essendemir Kurgi, decided to restore and rebuild StGilles Castle on the hill, so he incorporated what he could in his citadel, and made use of Roman column shafts and other building material he found nearby.

The City of Tyre, popularly mentioned in the Bible, is an ancient city inhabited by the Phoenicians. It was this city that we visited in Lebanon. The ruins of the old city left behind a sour taste of its conquest by Alexander the Great. In Dr. Rahme’s historical perspective, the siege of Tyre was orchestrated by Alexander the Great in 332 BC during his campaigns against the Persians. The Macedonian army was unable to capture the city, which was a strategic coastal base on the Mediterranean Sea, through conventional means because it was on an island and had walls right up to the sea. Alexander responded to this problem by first blockading and besieging Tyre for seven months, and then by building a causeway that allowed him to breach the fortifications.

The ruins of Baalbec Castle

It is said that Alexander was so enraged at the Tyrians’ defence of their city and the loss of his men that he destroyed half the city. 8,000 Tyrian civilians were said to have been massacred after the city fell. 30,000 residents and foreigners, mainly women and children, were sold into slavery.

A tour of the ruins of the city reveals several graves. The hippodrome in the city is still standing and in Rahme’s view, it can take 30,000 spectators during horse racing in those days.

The ruins of Tyre after Alexander the Great destroyed the city

Garden of Forgiveness

The garden of Forgiveness lies close to Martyrs’ Square and the wartime Green Line (1975-1990). It is surrounded by places of worship belonging to different denominations in Beirut and reveals many layers of Beirut’s past. According to Chady Rahme, Assistant Professor, NDU, who lectured on the garden, the place is central in the history of Lebanon and symbolizes unity as the different faith in the country after the end of the civil war in 1990 came together as one in the garden to pray.

The Garden of Forgiveness is an exemplary space since it touches the back walls of three churches and three mosques, making it a backyard to them all. It is a special place for inter-religious dialogue.

The brain behind the Garden of Forgiveness is Alexandra Asseily. Alexandra, an 81-year old and founder of the Silk Museum in Lebanon, told her story how the Garden of Forgiveness came into being.

As witness of the pain of the civil war in Lebanon (1975-199o), Alexandra decided to explore her own responsibility for war and peace and became a psychotherapist. In 1997, Alexandra had a life changing experience that inspired her to begin the Garden of Forgiveness (Hadiquat as Samah) in Beirut, a project to create a garden in the heart of the City to facilitate forgiveness.

Garden of Forgiveness

She is presently keeping the essence of the Garden of Forgiveness alive by a central project, entitled “Healing the Wounds of History: addressing the Roots of Violence”. The theory is that the cycles of violence between generations are healed by forgiveness and compassion. In the “Healing the Wounds of History” project people are taught to become aware and sensitive to the depth of their own and other’s traumatic memory and pain, which they may have experienced or unconsciously inherited. The release of this pain in traumatic memory, past or present, also releases the impulse to repeat the violence, inwardly or outwardly.

National Museum of Beirut

Other places of interest visited are the National Museum of Beirut. At the museum were preservations and artifacts dating back to prehistoric period. The museum, built in the Pharaonic style of the Egyptian Revival, from the nineteen-thirties, was ravaged. The museum had relics from the bronze and iron ages, as well as the Phoenician, Persian, Greek, Roman, Byzantine, Arab conquest, and Ottoman periods. There are also relics of the sarcophagus of Ahiram, the king of Byblos, dates to the tenth century B.C.; it features one of the earliest examples of the Phoenician alphabet. At the museum, is an enormous painted tomb, which was discovered in the Tyre region in the far south of Lebanon in 1937, spanning the second century AD, among several collections.

Human skeleton at the Museum of Beirut

Soyinka in Lebanon

Three days to our departure from Lebanon, Nobel laureate, Prof. Wole Soyinka and his wife, Folake were in Beirut. The Wole Soyinka Foundation is sponsoring the programme in Lebanon in conjunction with NDU and the Cedar Institute. Soyinka was first at the American University of Beirut, AUB to deliver a lecture, titled: “Oh-oh, Fables Sweeter than Facts: History, Culture and Revisionism.” The lecture was part of the NDU Louaize-organized SAIL/WSF–Nigeria programme. According to Soyinka, “we cannot be in denial to others’ cultures and world heritage: music, dance etc. Facts are the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.” AUD students had a staged reading from “Death and the King’s Horsemen,” a book published by Soyinka in 1974.

At the Garden of Forgiveness, Soyinka met with us in the presence of the exceptional woman who initiated the idea of this Garden, Alexandra. Soyinka also spoke about the untold story of the Asaba massacre during the Nigeria-Biafra War, and how General Yakubu Gowon (Rtd) begged for forgiveness over the massacre, while Alexandra shed light on the Lebanese civil war highlighting special cases of forgiveness in both.

L-R: Prof. Soyinka; Alexandra Asseily and Folu Soyinka at the Garden of Forgiveness

A dinner party at the Kalani Halat, organized by Dr. Habib Jafar, chief donor and promoter of the SAIL/WSF Nigeria project ended our adventurous stay in Lebanon. A special rendition on the Epic of Gilgamesh was rendered by participants of the 2018 SAIL project. It was championed by Lanre Fakeye, accompanied with guitar music by Osamudiamen Ivbanikaro-Isaac, popularly known as ‘Osas.’ Hundreds of audience at the event were thrilled to a scintillating performance.

END

Be the first to comment