When Ohio fell on election night 2008, the President’s Lounge, a bar on the overwhelmingly black south side of Chicago, erupted in jubilation. Corks popped, strangers hugged, police patrolling the streets yelled the freshly elected president’s name from their loudhailers: “Obama!”

When Ohio fell on election night 2008, the President’s Lounge, a bar on the overwhelmingly black south side of Chicago, erupted in jubilation. Corks popped, strangers hugged, police patrolling the streets yelled the freshly elected president’s name from their loudhailers: “Obama!”

As I scanned the faces at the bar, one woman looked at me, beaming, raised her margarita and shouted: “My man’s in Afghanistan. He’s coming home!” Barack Obama had never said anything about ending the war in Afghanistan. Indeed, he had pledged to ramp up the US military effort there. But she had not misunderstood him; she had simply projected her hopes on to him and mistaken them for fact.

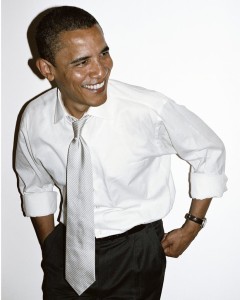

Obama had that kind of effect on people, back then. Often they weren’t listening too closely to what he was saying, because they loved the way he was saying it. Measured, eloquent, informed; here was a politician who used full sentences with verbs. He was not just standing to be the successor to George W Bush. He was the anti-Bush.

And they loved the way Obama looked when he said it: tall, handsome, black – an understated, stylish presence from an underrepresented, marginalised demographic. The notion that this man might lead the country, just three years after Hurricane Katrina, left many staring in awe when they might have been listening with intent. Details be damned: this man could be president.

Earlier on election day, I saw a grown man cry as he came out of the polling station. “We’ve had attempts at black presidents before,” Howard Davis, an African American, told me, “but they’ve never got this far. Deep in my heart, it’s an emotional thing. I’m really excited about it.” His voice cracked, and he excused himself to dry his eyes.

I first heard about Barack Obama from my late mother-in-law, Janet Mack, who lived in Chicago and joined his campaign for the Senate in 2003. That was the year I moved to the US as a correspondent for the Guardian, first in New York and later in Chicago, before moving back to London last August.

Janet had seen Obama on local television a few times and thought he spoke a lot of sense. She attended the demonstration where he spoke, as a state senator, against the invasion of Iraq. When he first ran, she feared he would be assassinated, but became accustomed to him as a primetime fixture. “It’s like living in California and the earthquakes,” she told me. “You just can’t worry about them all the time.”

We went to the south side of Chicago together to hear Obama’s nomination speech in 2008, watching with a couple of hundred others on a big screen at the Regal Theatre. People wept and punched the air. On the way home, Janet, a black woman raised in the Jim Crow south, punched my arm and laughed. Usually, she chatted a lot. But for most of the 30-minute ride she kept saying, to nobody in particular, “I just can’t believe it.”

In many ways Obama’s campaign for the presidency was unremarkable. He had voted with Hillary Clinton in the Senate 90% of the time. He stood on a centrist-Democratic platform, promising healthcare reform and moderate wealth redistribution – effectively the same programme that mainstream Democrats had stood on for a generation. But his rise was meteoric. His story was so compelling, his rhetoric so soaring, his base so passionate – and his victory, when it came, so improbable – that reality was always going to be a buzz kill.

Obama had long been aware that voters saw what they wanted in him. “I serve as a blank screen on which people of vastly different political stripes project their own views,” he wrote in The Audacity Of Hope in 2006. “As such, I am bound to disappoint some, if not all, of them.” But he was hardly blameless. He claimed to stand in the tradition of the suffragettes, the civil rights movement and the union organisers, evoking their speeches and positioning himself as a transformational figure. On the final primary night in June 2008, he literally promised the Earth to a crowd in St Paul, Minnesota: “We will be able to look back and tell our children that this was the moment… when the rise of the oceans began to slow and our planet began to heal.”

There was a lot of healing to do. When Obama came to power, the US had lost one war in the Gulf and was losing another in Afghanistan. In a poll of 19 countries, two thirds had a negative view of America. Americans didn’t have a much better view of themselves. The banking crisis had just sent the economy into freefall. Poverty was rising, share prices were nosediving, and just 13% of the population thought the country was moving in the right direction.

This was the America Obama inherited when he strolled, victorious, on to the stage in Chicago’s Grant Park with his family on election night in 2008 – a vision in black before a nation still in shock.

In Marshalltown, Iowa (population 27,800), on 26 January this year, a crowd waits in subzero temperatures for several hours to see Donald Trump while the hawkers enjoy a brisk trade. There are “Make America Great Again” hats (made in China), badges stating “Bomb The Shit Out Of Isis” and “Hillary For Prison 2016”. One man is carrying a poster with a picture of Hitler holding up a healthcare bill and saying, “You’ve gone too far, Obama!” Across the road are protesters, most of them Hispanic. Over the previous six months, Trump has branded Mexicans rapists, promised to exclude all Muslims from the country and insulted the Chinese, disabled people, women and Jews.

Inside, Sheriff Joe Arpaio from Arizona, an anti-immigrant zealot who still insists that Obama’s birth certificate is a forgery, introduces Trump, who emerges from behind a curtain as though walking out on to a game show. “Heeeeere’s Donald!” As the crowd grows into the hundreds, they open up the bleachers on the upper level for the overflow. For the most part, Trump blathers like a drunk uncle at a barbecue. He calls Glenn Beck, who has endorsed his principal rival Ted Cruz, a “nut job”. He brags about his wall to keep out the Mexicans. “It’s going to be a big wall,” he says. “A big beautiful wall. You’re gonna love this wall.” Afterwards, Brian Stevens, 37, tells me he thought Trump was impressive. “I don’t agree with everything he says. But I think he’ll make a difference – he has to. Someone’s got to stand up for America. We need him.”

Obama rocketed to national fame on the promise that there should be no more days like these. At the 2004 Democratic party convention, he described the nation’s partisan divide as though it had been imposed from the outside, by cynical operatives and a simplistic media: “spin masters and negative ad peddlers who embrace the politics of anything goes”. Back then, just over a year into the Iraq war, it looked as if America couldn’t get much more polarised. But it did.

When Obama stood in 2008, one of the central pledges of his campaign was that he would rise above the fray in a spirit of bipartisan cooperation. That’s not how it worked out. In 2010, the then Senate minority leader, Mitch McConnell, said the Republican party’s “top political priority over the next two years should be to deny President Obama a second term”. Republican congressmen, who refused to cooperate even with their own leadership, repeatedly threatened to bring the US to the brink of default, or simply shut the government down – unless Obama backed down from promises he’d made, or laws that had already been passed. A few years ago, as the Republican-led House of Representatives engineered a brief government shutdown, Congressman Marlin Stutzman illustrated how petulant Obama’s opponents had become: “We have to get something out of this,” he said. “And I don’t know what that even is.”

Regardless of what he said or did, President Obama was always going to be a lightning rod for political polarisation. Some argued that this was because the right could not come to terms with a black president, and there’s probably something to that. At times, when the Republicans refused to return his calls or refer to him as president, or when someone shouted “Liar!” during a presidential address, they appeared to refuse to recognise Obama as the legitimate holder of office.

But the issues went way beyond race: in all sorts of ways, he embodied the anxieties of a section of white America. He is the son of a Kenyan immigrant at a moment when America is struggling to come to terms with the impact of immigration and foreign trade. He is the son of a non-observant Muslim who came to power as the country was losing wars in predominantly Muslim lands. He is the product of a mixed-race relationship at a time when one of the fastest-growing racial groups in the nation is those who identify as “more than one race”. He is a non-white president who ends his term at a time when the majority of children aged five and under in America are not white.

Demographically and geopolitically, being a white American no longer means what it used to; Obama became a proxy for those who could not accept that decline, and who understood his very presence as both a threat and a humiliation. Trump, in many ways, is their response.

In his final state of the union address, in January, Obama conceded that he had not come close to achieving his dream of a more consensual political culture. “It’s one of the few regrets of my presidency,” he said, “that the rancour and suspicion between the parties has gotten worse instead of better. I have no doubt a president with the gifts of Lincoln or Roosevelt might have better bridged the divide, and I guarantee I’ll keep trying to be better so long as I hold this office.” With nine months left in an election year, it is difficult to see what would break the logjam.

By the end of Obama’s first term in 2012, there was a general sense that things hadn’t moved fast enough, that he had caved in to his opponents too easily. It was as though he negotiated with himself before reaching across the aisle, only to have his hand slapped away in disdain anyway. Having been elected on a mantle of hope, he seemed both aloof and adrift. Having moved people with his rhetoric, he was now failing to connect.

At a televised town hall meeting two years after his election, Obama was confronted by Velma Hart, an African American mother of two, who articulated the disappointments of many. “I’m exhausted,” she told him. “I’m exhausted of defending you, defending your administration, defending the mantle of change that I voted for, and deeply disappointed with where we are right now.”

A few months later, Hart lost her job as chief financial officer for a veterans’ organisation. By the time I met her, in the summer of 2011, she was re-employed but still far from impressed. “Here’s the thing,” she told me. “I didn’t engage my president to hug and kiss me. But what I did think I’d be able to appreciate is the change he was talking about during the campaign. I want leadership and decisiveness and action that helps this country get better. That’s what I want, because that benefits me, that benefits my circle and that benefits my children.”

“Do you think he’s decisive?” I asked.

“Ummm, sometimes…” she said. Like many, Hart wanted to support Obama, but felt he wasn’t making it easy. “Not always, no,” she added, after a pause.

The notion that strong individuals can bend the world to their will is compelling. It is also deeply flawed. “That’s what we’re taught to believe from an early age,” Susan Aylward, who used to work in an Ohio food co-op, told me. “We’re taught that one man should be able to fix everything. Abe Lincoln, George Washington, Ronald Reagan – history’s told as though it were all down to them. The world is way too complex for that.”

I first met Susan in 2004, coming out of the opening night of Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 in Akron. Back then, she said she intended voting for John Kerry because he wasn’t Bush, but she didn’t love him. Four years later, we had breakfast just a week before Obama was elected and she could barely contain her excitement. She made her two-year-old granddaughter, Sasha, who’s mixed race, sit up with her on election night. “We wanted her to be able to say she saw it that day, even if she didn’t really know what she was seeing.”

But when we caught up in 2012, Susan was processing her disappointment. “It’s not going to change my vote,” she said. “I just wish he could have been better. I don’t even know how, exactly. If you’re going to be president, then I guess you obviously want to be in the history books. So what does he want to be in the history books for? I don’t quite know the answer to that yet.”

When it comes to Obama, people have to own their disappointment. That doesn’t mean it’s not valid, just that it often says as much about them as it does about him. No individual can solve America’s problems. Most radical change in the US, like elsewhere, comes from huge social movements from below. Poor people cannot simply elect a better life for themselves and expect that vested interests won’t resist them at every turn: that’s not how western democracy works.

I supported Obama against Hillary Clinton because he had opposed the war in Iraq at a time when that could have damaged his political career; she had supported it in order to sustain her own. I thought he was the most progressive candidate that could be elected, and while even his agenda was inadequate for the needs of the people I most care about – the poor and the marginalised – it could still make a difference. I got my disappointment in early, to avoid the rush.

I appreciated the racially symbolic importance of Obama’s victory, and celebrated it. But I didn’t fetishise it, because I never expected much that was substantial to emerge from it. He leveraged his racial identity for electoral gain, without promising much in return. As a candidate, race was central to his meaning, but absent from his message. When I read the transcript of the nomination speech I saw with my mother-in-law on the south side that night in 2008, I realised he had quoted Martin Luther King but declined to mention him by name, referring to him instead as the “old preacher”. “If a black candidate can’t quote Martin Luther King by name,” I thought, “who can they quote?” I jokingly referred to him as the “incognegro”.

Obama never promised radical change and, given the institutions in which he was embedded, he was never going to be in a position to deliver it. You don’t get to become president of the United States without raising millions from very wealthy people and corporations (or being a billionaire yourself), who will turn against you if you don’t serve their interests. Congress, with which Obama spars, is similarly corrupted by money. Seats in the House of Representatives are openly and brazenly gerrymandered.

This excuses Obama nothing. On any number of fronts, particularly the economy, the banks and civil liberties, he could have done more, or better. He recognised this himself, and in 2011, shortly before his second election, produced a list of issues he felt he’d been holding back on: immigration reform, poverty, the Middle East, Guantánamo Bay and gay marriage.

By 2011, even those closest to Obama could see he was losing not only his base but his raison d’être as an agent of change. “You were seen as someone who would walk through the wall for the middle class,” his senior adviser David Axelrod told him that year. “We need to get back to that.”

Back then, Obama’s prospects looked slim. His campaign second time around was a far cry from the euphoria of the first. The president’s argument boiled down to: “Things were terrible when I came to power, are much better than they would have been were I not in power, and will get worse if I am removed from power.” What started as “Yes we can” had curdled into “Could be worse”.

But Obama has always been lucky in his enemies. The Republican party effectively undermined and humiliated their nominee, Mitt Romney, who then proved a terrible candidate. In 2012, I went to vote with Howard Davis, the man I’d met weeping at a Chicago polling station back in 2008, who voted Obama again. There were no tears this time. In the words of Sade, it’s never as good as the first time.

***

As Obama comes to the end of his tenure, we are no longer confined to discussing what it means that he is president; we can now talk in definite terms about what Obama did. Indulging the symbolic promise of a moment is one thing; engaging with the substantial record of more than seven years in power is quite another.

Everybody has their list. None is definitive. Obama withdrew US soldiers from Iraq (only to resume bombing later), relaxed relations with Cuba, executed Osama bin Laden, reached a nuclear deal with Iran and vastly improved America’s standing in the world. Twenty million uninsured adults now have health insurance because of Obamacare. Unemployment was 7.8% and rising when he came to power; today, it is 4.9% and falling. He indefinitely deferred the deportation of the parents of children who are either US citizens or legal residents, and expanded that protection to children who entered the country illegally with their parents (the Dream Act). Wind and solar power are set to triple; the automobile industry was rescued. He eventually spoke out forcefully for gun control. He appointed two women to the Supreme Court, Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor, the first Latina. When those on the left question Obama’s progressive bona fides, this is generally the list that is read back by his defenders – as though mimicking John Cleese in Life Of Brian when he asks, “What have the Romans ever done for us?”

There are, of course, other facts to contend with. Obama escalated fighting in Afghanistan and the troops are still there; deported more people than any president in US history; used the 1917 Espionage Act to prosecute more than twice as many whistleblowers as all previous presidents combined; oversaw a 700% increase in drone strikes in Pakistan (not to mention Yemen, Somalia and elsewhere), resulting in between 1,900 and 3,000 deaths, including more than 100 civilians; executed US citizens without trial; saw wealth inequality and income inequality grow as corporate profits rocketed; led his party to some of the heaviest midterm defeats in history. In Syria, he drew a red line in the sand and then claimed he hadn’t; he said he wouldn’t put boots on the ground, and then he did.

The discrepancies between Obama’s campaign promises and his record in office have been most glaring on matters of civil liberties. “This administration puts forward a false choice between the liberties we cherish and the security we provide,” he said as a candidate on 1 August 2007. “You can’t have 100% security and then 100% privacy and zero inconvenience,” he said on 7 June 2013, during the Edward Snowden affair. “We’re going to have to make some choices.”

And finally, there are the things Obama didn’t do. He didn’t pursue a single intelligence officer over torture; he didn’t pursue a single finance executive for malfeasance in connection with the 2007/8 crash; he didn’t close Guantánamo Bay.

But a legacy is not a ledger. It is both less substantial than a list of things done, and more meaningful. “At some point in Jackie Robinson’s career, the point ceases to be how many hits he got or bases he stole,” Mitch Stewart, who played a leading role in both Obama campaigns, tells me. “As great and important as all these stats were, there was a bigger picture.”

Legacies are about what people feel as well as what they know, about the present as much as the past. Aesthetically, there has always been something retro about Obama’s public profile. The original campaign posters announcing “Hope” and “Change”; the black-and-white video clips in will.i.am’s Yes We Can video. With his family at his side, his brand offered not glamour exactly, but chic. Like John F Kennedy, he projected an image that enough Americans either wanted or needed, or both: a young, good-looking family, a bright future. He offered Camelot without the castle: no ties to the old, all about the future.

Photographs of Obama at the White House suggest both he and Michelle grew into this role quite happily. Whether it was Michelle dancing with kids on the White House lawn or Barack making faces at babies and chasing toddlers around the Oval office, they returned a sense of playful normality to the White House: an unforced conviviality that did not detract from the gravity of office.

“It’s important to remember that he was more recently a normal person than most people at that level,” one veteran member of his team told me. “For the 2000 convention, he couldn’t even get a floor credential. In 2004, he introduced the presidential nominee. In 2008, he was the nominee. It’s tough to see him and Michelle, and not give him that benefit of the doubt. He’s had small kids in the White House. I think people will remember that as a moment and an era.”

When Virginia McLaurin, a 106-year-old African American woman, was granted her lifelong dream to visit the White House earlier this year, the president and his wife danced with her quite unselfconsciously. “Slow down now, don’t go too fast,” Obama joked. As the second term has progressed, they have seemed happy in their skin – and, for many, the novelty that it is black skin has not worn off. “I thought I would never live to get in the White House,” McLaurin said, looking up at her hosts. “I am so happy. A black president, a black wife, and I’m here to celebrate black history.”

***

Legacies are never settled; they are constantly evolving. A few years before he died, almost two thirds of Americans disapproved of Martin Luther King, because of his stance against the Vietnam war and in favour of the redistribution of wealth. Yet within a generation, his birthday was a national holiday; when Americans ranked the most admired public figures of the 20th century in 1999, King came second only to Mother Teresa.

Ronald Reagan is now hailed as a conservative hero, even though he supported amnesty for undocumented migrants and massively inflated the government deficit. During the final year of Bill Clinton’s presidency, most guessed that his legacy would be one of scandal. Instead, he was hailed for presiding over a sustained economic recovery. But as his wife seeks the Democratic nomination, he has had to recant key parts of that legacy – the crime bill, welfare reform, financial deregulation – those elements which have disproportionately impoverished African Americans and enriched the banks.

“History will be a far kinder judge than the current Republican congress,” Stewart tells me. “It will rest on the untold successes that this administration has had. Energy efficiency, carbon efficiency. He reformed the student loan programme, which is going to have an impact on a generation of students. He’s catapulted the US forward in ways that will continue to pay dividends long after his presidency. His legacy will be about these smaller, unsung accomplishments that will have a generational impact.”

Paradoxically, the element of Obama’s legacy for which he will be best remembered – being the first black president – relates to an area that has seen little substantial headway: racial equality. The wealth gap between black and white Americans has grown, as has the unemployment gap and black poverty; black income has stagnated. That’s not to suggest he has done nothing. He has appointed an unprecedented number of black judges, released several thousand nonviolent drug offenders, reduced the disparity in sentencing for crack and powder cocaine. Anything he did that helped the poor, like Obamacare, will disproportionately help African Americans.

But, broadly speaking, Obama’s racial legacy is symbolic, not substantial. The fact that he could be president challenged how African Americans saw their country. The fact that their lives did not radically improve as a result did not shift their understanding of how America works. When he was contemplating a run for the White House, his wife asked him what he thought he could accomplish if he won. “The day I take the oath of office,” he replied, “the world will look at us differently. And millions of kids across this country will look at themselves differently. That alone is something.”

The imagery did not, in the end, translate quite so neatly. True, when Trayvon Martin was shot dead by George Zimmerman in 2012, Obama was able to say what no other president could have said: “Trayvon Martin could have been my son.” Nonetheless, it is unlikely that Zimmerman looked at Trayvon and thought, “There goes the future president of America.” Thanks to Obama, Americans see racism differently; they do not, however, view black people differently.

Obama will leave office during a period of heightened racial tension over police shootings. “His presidency was supposed to pass into an era of post-racism and colour blindness,” Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, Princeton professor and author of From #BlackLivesMatter To Black Liberation, tells me. “Yet it was under his administration that the Black Lives Matter movement erupted. In many ways, it’s the most significant anti-racist movement in the last 40 years, and it happens under the first black president. The eruption of this movement can be interpreted as a disappointment in the limitations of the Barack Obama presidency. And some of those limitations can be explained externally, by the hostility with which he’s been met by the mostly Republican congress. But some of it lies in the limitations of his own policies.”

Over the past couple of years, the #BlackLivesMatter debate has taken place almost without reference to Obama. It suggests that, on one level, his relationship to some of the key issues surrounding black life is almost ornamental. He is the framed poster in the barbershop or the nail salon, the mural on the underpass, the picture in the diner or bodega – an aspiration not to be mistaken for the attrition of daily life. The question as to whether America can elect a black president has been answered; the issue of the sanctity of black life, however, has yet to be settled.

***

At the Col Ballroom in Davenport, Iowa, on 29 January, it is difficult not to feel nostalgic. Built in 1914 and listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the chandeliers both illuminate and illustrate the regal atmosphere of an old music hall, while the posters bear witness to the greats who have played there, from Duke Ellington to Jimi Hendrix.

So when the swing band stops playing and Bill Clinton steps on stage to present his wife, Hillary, the sense that you have stepped back in time feels complete. Hillary has become a far more animated candidate since she lost to Obama here eight years ago. Heather Johnson, a precinct captain whose job is to rally support in her area, has been knocking on doors, calling supporters and galvanising the local faithful for months now. “After she lost last time, I decided, if she ran, I’d do everything I could to make sure she didn’t lose again,” she says. “Who else has her experience?”

It’s just a few days before the caucuses and this mostly older crowd is energised. But Hillary still suffers from the same vulnerabilities as in 2008. She is seen as an insider, when the voters want change. She remains dogged by scandal – her emails sent via a private server – and voters find her untrustworthy. She promises progress by increments, rather than transformation. She even tries to make a selling point of the fact that her platform is not exciting. “I’d rather underpromise and overdeliver,” she tells the crowd. She is effectively running for Obama’s third term, asking for the opportunity to continue what he started.

A few days earlier, at Grinnell College, Bernie Sanders offered a younger crowd a future more radical and bold – free healthcare, no tuition fees, a $15-an-hour minimum wage – and a clear departure from a political culture corrupted by money and corporate influence. Sanders has reservations about Obama’s legacy; he recently endorsed a book called Buyer’s Remorse: How Obama Let Progressives Down. But on the stump he knows there is no mileage in criticising the president.

This crowd likes Obama. His second term has been more sure-footed than his first. Following the Sandy Hook shootings, when 20-year-old Adam Lanza killed 20 schoolchildren, six adult staff, his mother and himself, Obama finally vowed to challenge the legislative inertia on gun control and has not stopped since. As the Republicans have proven themselves incapable of compromise, Obama has felt more licence to stamp his authority on the political culture. A few months after the midterms, he signed the Dream Act; last November, he vetoed the Keystone Pipeline, from Canada to the Mexican Gulf, because of environmental concerns. While other presidents use the lame duck portion of their tenure to get to work on their presidential libraries, Obama has been tying up loose ends. “He’ll be a blueprint for how you have a second term,” Mitch Stewart thinks. “Every day there is an hourglass mentality.”

Karen Sanchez, a 19-year-old Sanders supporter in Marshalltown, Iowa, tells me she thinks Obama has done a great job. “He did what he could. I think he would have done more, but they kept blocking him.” A Hillary supporter at an event in Adel, Iowa, who did not want to give her name, agreed. “He gave it his best shot,” she said. “I don’t think anyone could have done better when you’re up against people who just want to stonewall you.”

This was the standard response at any Democrat event when I asked how people thought Obama would be remembered: effectively a phantom legacy. Not what he actually achieved, but what he might have achieved if the other side weren’t so unreasonable. As endorsements go, this seemed like faint praise. Like the 1986 World Cup England might have won were it not for Maradona’s hand of God, or the Gore presidency that might have been were it not for hanging chads and the Supreme Court, the case for Obama’s legacy was the subjunctive – what might have been. Yes. We. Tried.

But as the primary season has drawn on, what looked like a partial and qualified stamp of approval has been developing into something more complete and adulatory. Compared with the frontrunners, carnival barkers and showmen, Obama is starting to walk taller and appear smarter than ever.

The day after a recent Republican debate, CNN ran the headline, “Trump Defends Size Of His Penis”, after Trump objected to Marco Rubio’s allusion that, because Trump had small hands, he has a small penis. “Look at these hands; are they small hands?” Trump asked a cheering crowd. “I guarantee you, there’s no problem.”

When the political tone is set this low, when so little is expected of the candidates and the choices are this poor, the fact that Obama tried – and the way that he tried – starts to eclipse the fact that he so often failed. Like a dutiful doctor, he performed triage on a reluctant patient and didn’t give up even when the prospects looked bleak. He did his job.

As his term comes to an end and the fractured, volatile nature of the country’s electoral politics is once again laid bare, Americans may be coming to realise that, in Obama, it had an adult in the room. As violence erupts at election rallies and spills over into the streets, they may come to appreciate the absence of scandal and drama from the White House. As their wages stagnated, industries collapsed, insecurities grew and hopes faded, he tried to get something done. Not much, not enough – but something. It is possible to have serious, moral criticisms of Obama and his legacy, and still appreciate his value, given the alternatives.

In Obama, Americans are losing someone who took both public service and the public seriously; someone who stood for something bigger and more important than himself. This is the end of the line for a leader who believed that facts mattered; that Americans were not fools; that their democracy meant something and that government had a role: that America could be better than this.

END

Be the first to comment