From selfies on super-yachts to posing with private jets, the young heirs of the uber-wealthy have attracted worldwide envy and derision by flaunting their lavish lifestyles on social media.

But these self-styled rich kids of Instagram are, often unwittingly, revealing their parents’ hidden assets and covert business dealings, providing evidence for investigators to freeze or seize assets worth tens of millions of pounds, and for criminals to defraud their families.

Leading cybersecurity firms said they were using evidence from social media in up to 75% of their litigation cases, ranging from billionaire divorces to asset disputes between oligarchs, with the online activity of super-rich heirs frequently providing the means to bypass their family’s security.

Oisín Fouere, managing director of K2 Intelligence in London, said social media was increasingly their “first port of call”. Their opponent in one asset recovery case claimed to have no significant valuables – until investigators found a social media post by one of his children that revealed they were on his $25m yacht in the Bahamas.

Daniel Hall, director of global judgment enforcement at Burford Capital, said their targets in such cases tended to be people “of a slightly older vintage” who were not prodigious users of Instagram, Facebook and Twitter, but whose children, employees and associates often were. The firm recently managed to seize a “newly acquired private jet” in a fraud case because one of the two fraudsters had a son in his 30s who posted a photograph on Instagram of himself and his father standing in front of the plane.

“That’s the kind of jackpot scenario one hopes for,” said Hall.

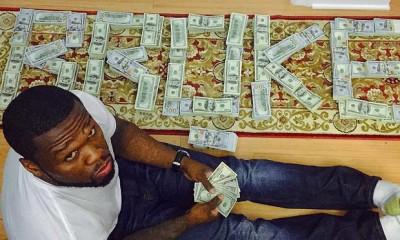

The growing significance of social media in litigation was recently illustrated by rapper 50 Cent, who was ordered by a Connecticut court last month to explain a photo on Instagram in which he posed with stacks of $100 bills that spelled out “broke”, months after filing for bankruptcy. The rapper claimed the money was fake.

Hall, a former lawyer turned corporate investigator, said most investigations were more complex, and involved using social media to map a target’s family and business networks. For example, they might use the metadata embedded in an Instagram post to identify their location, or use a Facebook “like” or tag to track down a proxy company. He said: “You can start building up a profile of that individual: where they are; what their interests are; who are they regularly in touch with?”

Another of Hall’s fraud cases involved the Russian chief executive and major shareholder of a collapsed Russian bank. His lawyer argued that the case should not be brought in the UK, as it was not his primary residence. “Part of the evidence we used was social media, chronologically showing data posts of the family members and the principal himself … living and operating here, so [proving] the UK is the correct jurisdiction,” said Hall. Investigators often use location search tools such as Geofeedia, which enable them to throw a virtual “geo-fence” around a certain building or area and gather all of the social media posted from there in real time.

Andrew Beckett, managing director of cybersecurity and investigations at Kroll, said the firm uncovered multimillion-pound hidden assets in a divorce case last year by monitoring the location of the children’s social media posts. The court ordered the husband to give his wife $30m, but he claimed not to have such assets.

“We monitored social media, particularly for his children, who were in their 20s, and found a lot of posts from the same geo-tagged sites,” said Beckett. “Cross-referencing that with land registry and other similar bodies overseas, we found half a dozen properties that were registered in the name of this person.

“We were able to go to the court with a list of assets that we conservatively estimated at $60m, which the court then seized until he settled the amount that had been ordered.”

Beckett said the social media indiscretions of super-rich heirs were also leaving their families vulnerable to fraud and extortion, with high-net-worth individuals and families probably losing collectively several hundred million dollars each year due to cybercrime. The most recent case investigated by Kroll involved defrauding a family office, a private company that manages the wealth of families typically worth at least $250m.

An heiress had her email account hacked because the password was the name of her dog, which was plastered all over her social media posts. When she went on holiday, the hackers sent spoof invoices for private jets, luxury villas and shopping sprees to the family office, which paid out $900,000 before the crime was detected. “It was only when dad got cross about the size of the bills she was racking up that somebody thought to contact her and query it,” said Beckett. “It is that easy.”

Fouere said that K2 Intelligence had seen an exponential rise in such cases in the last year, as cybercrime groups increasingly targeted wealthy families as well as corporations. “We had a case recently where the payment instruction was for $500,000 and it was executed,” he said.

Jordan Arnold, the head of private client services at the firm, said it was helping the super-rich to devise family social media policies that set out a code of conduct for posting sensitive content, such as images of their properties, yachts and jets.

END

Be the first to comment