The hope raised in London the other day when world leaders pledged to make corruption a top priority and take necessary actions to prevent the scourge from festering in governments, institutions, businesses and communities all over the world, should not be allowed to be a tale told by those leaders full of sound and fury, signifying nothing, after all.

The renewed pledge to be serious about corruption emanated from the London Summit where a communiqué was signed on a common approach to tackling the cankerworm and appropriate international organisations were endorsed. While the leaders identified corruption as the root of “so many of the world’s problems,” they vowed to expose the menace across board. They reportedly committed themselves thus: “We see tackling corruption as a top priority, at home and abroad. We will take action to prevent corruption and to ensure it does not fester in our government institutions, businesses and communities. We will seek to uncover corruption wherever it exists, and to pursue and punish those who perpetrate, facilitate or are complicit in it…We commit to make it easier for people to report suspected acts of corruption, and to support communities that have suffered from it.”

One of the most significant aspects of the commitment to the action plan is their assurance that they will fully implement the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) Recommendations on Transparency and Beneficial Ownership of Legal Persons and Arrangements. Not only that, the leaders assured that they would take concrete steps to “eliminate loopholes that allow corruption to thrive through the misuse of these entities, and work in accordance with national laws, to ensure a level playing field between foreign and domestic companies in respect of requirements to provide beneficial ownership information.”

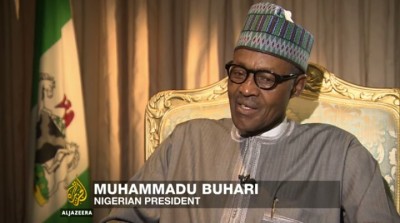

This remarkable commitment came to light as President Muhammadu Buhari, also a participant at the conference, called for restriction of movement of corrupt persons. He had noted in clear terms that he was in favour of a diplomatic initiative of restricting corrupt persons from travelling, investing and doing business abroad. Besides, the Nigerian leader had also disclosed a policy support strategy known as Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS), to combat corruption.

As Nigerians welcome this new policy instrument for fighting corruption, the President should be reminded of the need to also implement provisions of the Public Procurement Act (2007). According to the law, there shall be a National Procurement Council to be headed by the Finance Minister. The council comprises many professional bodies from outside the public sector including Architects Council, Quantity Surveyors’ Council, Nigeria Union of Journalists, etc. The council, which also includes the Attorney-General of the Federation as a member, effectively restricts participation of the Federal Executive Council (FEC) in procurement.

This, no doubt, will enhance the Open Contracting Data Standard now being enunciated. In fact, the focal point of the OCDS should be the National Procurement Council. Unfortunately, contrary to the 2007 Procurement Act, the Director-General of the Procurement Bureau who shall serve as Secretary to the National Procurement Council has since 2007 run the Bureau without a council and the federal cabinet has continued to handle contract awards in defiance of the law that has not been amended. This executive lawlessness should be redressed as another one of those steps towards fighting corruption.

Meanwhile, the world leaders who have committed themselves to the fight against corruption should remember the Buhari’s charge that the international community had kept quiet about corruption for too long and had allowed the scourge to thrive to the detriment of nations like Nigeria. Not only that, there should be a global support for the call by Buhari for the creation of an anti-corruption infrastructure and a strategic action plan to facilitate the speedy recovery and repatriation of stolen funds hidden in secret bank accounts abroad.

However, leaders of Western countries who are too adept at preaching about corruption have been perpetual promise makers and breakers. For instance, hope raised at the 2005 Gleneagles, Scotland Summit at which Western countries made pledges of aid to the developing countries have remained a mirage. It was a “Make Poverty History Summit” after the annual monitoring report on aid found that financial assistance had fallen well short of the levels envisaged.

It is, therefore, important to put it on record that the promises made at the London Summit on Corruption in 2016 are too vital to the survival of nations and must not go the way of promises like that of Gleneagles 2005.

END

Be the first to comment