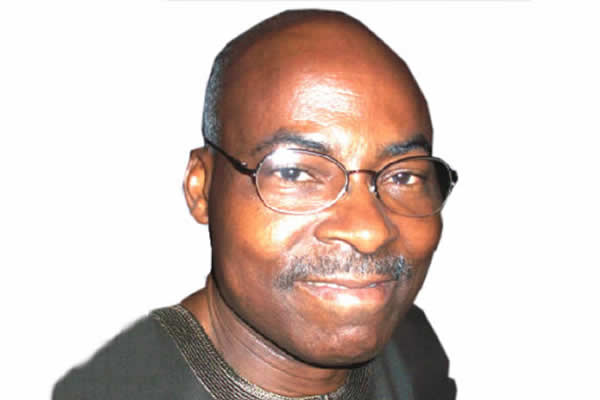

The Ondo State Governor, Dr. Olusegun Mimiko, is no doubt a fighter. He sure knows well how to fight a political battle. It will be recalled that he came into office after an electoral controversy, which led to a two-year legal tussle at the end of which the Court of Appeal ruled in his favour. He fought another legal battle on his re-election, when at least two opposition parties contested his victory in the election. He also won that battle.

However, he needs to be very careful about how he fights the ongoing battle for the governorship candidate of the Peoples Democratic Party in the November 26, 2016, election in his state. Everyone knows his side in the battle as well as his faction in the PDP. He belongs to the Ahmed Makarfi faction, which arranged the primary election that Eyitayo Jegede (SAN) won. It is also well-known that there is no love lost between Mimiko and Jimoh Ibrahim, who won the primary of the Ali Modu Sheriff faction. It is further known that the Independent National Electoral Commission recently replaced Jegede with Ibrahim as the party’s candidate in response to a court order. At least, eight different court motions were filed against the court order, which are being handled by the Court of Appeal. The legal battle should have been allowed to run its course without intervention.

Mimiko has a duty to ensure that Ondo State is not used to settle scores in a year-old power struggle between the two factions of his party. On the one hand, if he eventually succeeds in getting Jegede’s name back on the ballot, he must ensure that the celebration of the joy of victory does not degenerate into rampage in major cities. On the other hand, if he loses the battle, he must also ensure that the agony of defeat does not lead to wanton violence.

For, if the state burns, it will burn under his watch both as the Chairman of the PDP Governors’ Forum and as the incumbent Governor of Ondo State. And that will be an indelible negative legacy. He should not allow his eight-year governorship tenure, with notable landmark achievements, to be sandwiched between two political upheavals arising from power struggle.

That’s why the pro-Jegede protest last weekend, involving bonfires and a mock coffin of Ibrahim and Justice Okon Abang, was a bad omen. Already, the protest has reportedly claimed one casualty said to be a student of St. Joseph’s College, Ondo, the governor’s alma mater.

It is unfortunate that the rhetoric of the protest has included references to Operation Wetie of 1962-65, when some notable local politicians in the opposition party were drowned in petrol and set ablaze or had their property destroyed, and the post-election violence of 1983, following the rigging of the governorship election in favour of the candidate of the opposition National Party of Nigeria, the late Chief Akin Omoboriowo, when some notable politicians of the NPN were killed or had their property destroyed.

Both events occurred during inter-party struggles for power, driven largely by the inordinate ambition of some politicians, who wanted to be the regional or state chief executive by all means. True, the events sharpened the citizens’ political consciousness and their aversion to cheating, especially vote rigging; but the ongoing electoral tension in Ondo State is of a different order. Yes, it is still being driven by the politicians’ self-interest, but the struggles so far are limited to the internal squabbles within the PDP over who should be the party’s candidate for the November 26 governorship election. It lacks the scope and potency of the two post-election crises to which it is being compared.

Incidentally, a similar internal struggle occurred during the governorship primary of the All Progressives Congress, which is equally traceable to factionalism within the top hierarchy of the political party. However, the historical trajectories and operations of the two factions within each of the parties are vastly different. While the factions within the PDP are visible and well-known, those within the APC operate in the background, surreptitiously pitting the National Leader of the party, Bola Tinubu, against the party Chairman, John Odigie-Oyegun, on the one hand, and President Muhammadu Buhari, on the other hand.

For example, the delegates list for the APC primary election was allegedly manipulated in favour of the candidate who eventually won, namely, Rotimi Akeredolu (SAN), leading to discrepancies between the authentic delegates list circulated to all aspirants a week before the primary and another list surreptitiously compiled in Abuja and used for the primary election. As many as 24 aspirants participated in the election, meaning that 23 of them felt cheated. At least, three of the aspirants and some delegates petitioned the party’s Appeal Committee, which recommended a rerun.

The two factions within the National Working Committee of the party became evident when the minority faction, led by the party’s Chairman, Odigie-Oyegun, sidetracked the Appeal Committee’s recommendation and submitted the name of Akeredolu to INEC.

Consequently, one of the aggrieved aspirants, Segun Abraham, who came second in the primary, went to court to challenge the results of the primary, the manipulation of the delegates’ list, and even the qualification of the winning candidate to contest in the governorship election. Another aspirant, Chief Olusola Oke, who led in the polls leading to the primary election, left the party and eventually became the candidate of the Alliance for Democracy.

However, in none of the APC struggles was a bonfire set up on a major highway. Rather, their struggles were limited to verbal duelling among their members, protests at their party secretariat, and litigation. This is not to say that the APC is a political angel. We all know that it is afflicted with various internal problems. But the party has handled its own internal squabbles over its party primary in Ondo differently.

There are lessons to learn from the conduct of the politicians in both parties. They all show us how not to grow a democracy. It is normal for factions to develop around the political ambition of some party members. The stunted growth of our democracy is evident (a) in the politicians’ inability to resolve factional disputes according to the rule of law and the laws of decorum and (b) in their inability to conduct free and fair primary elections. It is instructive that the Ondo primaries came on the heels of the American Presidential primaries. It is unfortunate that our politicians learnt nothing from how the Democrats and Republicans handled the factionalism that developed within their political parties in the course of their primaries.

Electoral matters apart, it is unfortunate that the PDP has virtually abandoned its rightful role of a virile opposition, engaging instead in repeated dogfights between two warring factions. It is further unfortunate that Ondo has become a site for such a fight.

There are lessons too for security agencies in the state, especially the police and the Department of State Services. If this much protest could accompany the struggle over party candidacy for the governorship election, then the security agencies should be prepared for war during the governorship election proper. Of course, it need not be so. But that is the pattern our political culture has taken because many citizens, from politicians and contractors to thugs and area boys, depend on major political events or access to political power for their livelihood.

Perhaps, one good thing that may come out of the PDP candidate crisis in Ondo is a clear indication from the Court of Appeal as to the authentic party chairman so that the PDP can once again be one political family and play its expected role as the opposition.

Punch

END

Be the first to comment