man keeps sliding through my door. Dressed in blue hospital scrubs, he wears a hostly smile and a beard sprinkled with grey to denote experience. The leaflet he is on asks a question: “Tired of waiting?” It also has an answer: “Private treatment made easy”.

I’ve never had a surgeon flop on to my doormat before. Discounts for a Domino’s, yes. Ebulliently misspelt flyers about guttering, naturally. But this is the first time private hospitals have asked over and over if sir fancies a scalpel somewhere intimate. And opening the leaflet from Circle, I find promises galore. “Eliminate the wait,” urges the UK’s largest private hospital group, while “treatment is more affordable than you think” is above a price list: knee replacements start at £13,250, a hysterectomy goes for nearly £9,000, and snipping out your child’s tonsils costs “from £3,276”.

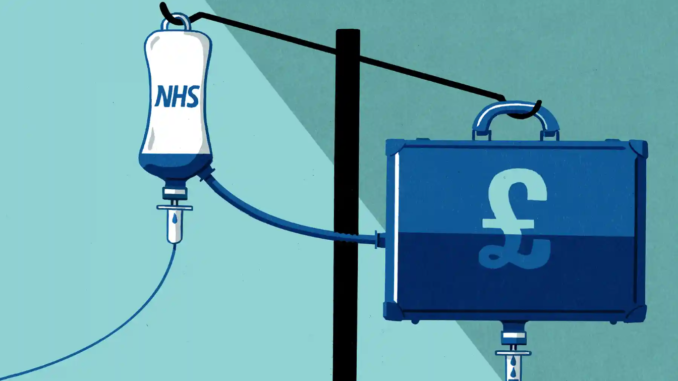

If those sums sound stretching, the leaflet advises, I can spread the cost with a whole suite of loans. Get that titanium hip 12 months interest free! And shopping around is easy, too. Why, midway through the paragraph above, another leaflet arrived, from a rival chain of hospitals. If you want to see just how our NHS gets privatised, this is the moment to study your junk mail.

Perhaps you’re among the more than one in 10 English people waiting for routine hospital treatment. Maybe you’ve read about the massive cuts looming in cancer care and GP appointments and wondered at the misery to come. But there are a few for whom this purgatory of pain is great business. For those who own and run private hospitals, it spells millions in extra profits. Because when patients can no longer stand the years and the uncertainty of hoping they can get a hernia repair or a colonoscopy, they end up paying out of their own pockets or sinking into debt to see a private firm.

Look no further for an example than the letters pages of this newspaper. It was there, two weeks ago, that Philip Wood of Kidlington told his own story. “I was on an 18-month waiting list for laser surgery on my prostate. Informed of little hope of medium-term surgery, I opted for private treatment, saw a urologist within a fortnight and was operated on shortly after.” He describes himself as a “desperate pensioner”, out of options. There are so many like him, a whole army of the unwilling.

An entirely new customer base is taking shape, more provincial and poorer than is traditional – and defined by their despair. London has always been the centre of private medicine, but according to the latest figures, Wales has seen the number of people going private more than double in the first three months of this year compared with the same period in 2019, while in Scotland it has shot up by 72%. Contrary to stereotypes of private medicine, they’re not after bigger breasts or thatched bald spots. In 2022, there has been a tripling of the numbers of patients after hip replacements, while the number one procedure is removing cataracts.

This country prides itself on its public healthcare, yet within the first three months of this year, more than 12,000 Britons each scraped together thousands of pounds just to be able to see. For the private health firms, this spells boom time. The biggest private hospital group listed on a UK stock exchange is Spire Healthcare, which grew out of the Bupa group. In the first six months of 2022, it took £174m from patients paying out of their own pockets – nearly as much as it made in the whole of 2019. Private firms have watched Tory PM after Tory PM starve the NHS of funds. They are prepared. As David Rowland of the Centre for Health and the Public Interest says, “Multinational investors have bet against the NHS for years, knowing this moment would arrive.”

All this fits a pattern that keeps repeating in these years of austerity. Something vital in the public sector is squeezed almost out of existence – and then its ad hoc, improvised, inadequate replacement becomes the new norm. Within a decade, food banks have become part of the welfare state. People within the charity sector have told me to expect the same to happen with “warm hubs”, the community centres and churches opening this winter to ensure locals don’t freeze; they will be a permanent fixture by 2030. So it will be with paying for your own elective procedures. “Attitudes are changing,” says the boss of Spire, Justin Ash. This is a “fundamental shift”.

Whole swaths of the NHS are restricting patients to the removal of cataracts in only one eye, not both, I was told by Anita Charlesworth of the Health Foundation. Which leaves no alternative for those who want to see, apart from to go private. Spire’s own analysis shows that demand has soared 54% among households earning less than £40,000 a year. For a family already just scraping by, a knee op spells financial ruin. Where do they go to raise such sums?

One answer is to follow the example of poor Americans or Indians, and beg strangers on the internet. The crowdfunding website GoFundMe told me they’ve noticed a big increase this year in the number of UK medical fundraisers, with a 31% rise from 2019 in those mentioning MRI and a 127% jump in those seeking cash for hip replacements.

Take a young man called Aidan, who has had a bone deformity since childhood. He is now suffering “an unbelievable amount of pain” and has tried everything from physio to massages to medicine (“I’m completely maxed out on all the drugs,” he says). He needs surgery – but the doctor says there’s a long wait. Mid-consultation, he breaks down: “I can’t wait 12 months, doc, I’ve no quality of life now.” So here he is, “out of ideas and clutching at straws”.

At the root of all this misery is an irony. All those extra thousands of pounds people are now having to spend are only to jump the queue, because private hospitals train no doctors and employ barely any consultants of their own. As Philip Wood writes in his letter, the urologist he paid so much to see gained his experience in the NHS. And those private hospitals are only in business because of the subsidy they’ve received over decades from the taxpayer. During the pandemic, the sector was bailed out by the then health secretary, Matt Hancock, to the tune of at least £2bn – in return for which it treated a grand total of eight coronavirus cases a day.

Here in miniature is the story of the UK since 1979: the public sector hacked back while private firms are handed taxpayers’ money to replace it. Pensioners and ordinary working people are forced to pay for their own care even while incomes shrink and their costs soar. And so the social contract that holds together the NHS and so much else is shredded.

This is the system that you and I have to endure, and for which we have to foot the bill. Yet I don’t recall seeing it advertised on a leaflet.

Aditya Chakrabortty is a Guardian columnist

END

Be the first to comment