First, let me tell Mr. President right away that if he hopes to grow the economy out of recession in 2017, the appropriation bill submitted recently at the National Assembly is not the one to do it. This is because it is not expansionary, pro-investment, pro-growth, and pro-jobs enough to be expected to perform such a magic.

Let us agree that like most recessions, our present recession is not a product of a sudden accident. That is why this conviction in sending this economy to the emergency ward does not arise.

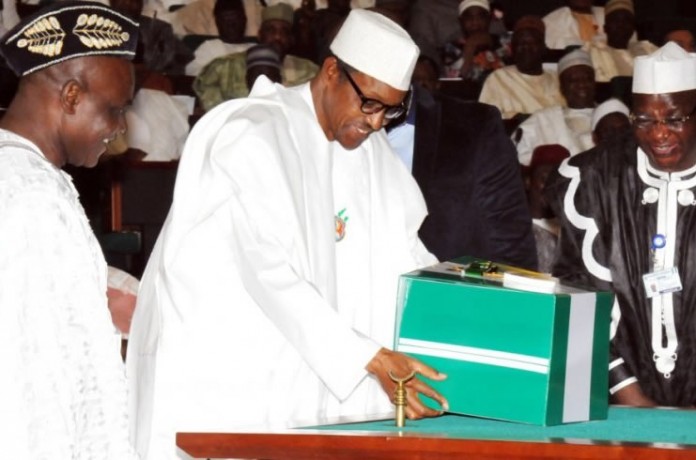

Like every recessionary economy, this economy too urgently needs a serious restructuring along with unconventional policies, designed to permanently put it on a healthy and sustainable growth path. This has not yet happened because President Muhammadu Buhari has yet to bring together those gifted pro-expansionary Nigerians to begin performing this inevitable economic diversification surgery.

That is why the 2017 budget proposal with all the good intentions, rather than being an expansionary budget, is a contractionary one because it is smaller than the 2016. This, we can see comparing the 2016 budget and the 2017’s. A look at the proposed 2017 budget’s N7.298tn seems higher than the 2016’s N6.077tn in size.

But, then, taking N305 per dollar and over 18 per cent inflation average into consideration against 2016’s N197 per dollar and 16 per cent inflation average, it becomes certain that 2017 budget is smaller. It becomes far less expansionary than the 2016 with N2.24tn capital budget at N305 per dollar is only $7.344bn against N1.8tn capital spending at 197 per dollar is $9.137bn.

No doubting the good news that for the first time since 1999, a large portion of government’s fiscal deficit is funded through external borrowing; unlike the usual high domestic borrowings, not minding the cut-throat rates government contended with. But what should have been the justifications for government borrowing domestically that between 2013 and 2016 we borrowed N2.721tn against N900bn external borrowing? This is notwithstanding that our low savings culture and the financial sector’s low liquidity.

The only reason why this has been going on is because of the fact that top fiscal and monetary policymakers along with those in charge of the Debt Management Office, have been conniving with their local bank counterparts to use bloated domestic borrowing to defraud the country trillions of naira. This is confirmed by the N3.628tn spent on domestic debt service against N217bn on external debt service.

What economic sense does it make that a country with $350bn infrastructure deficit is okay with 14 per cent debt to the GDP ratio (with external portion less than two per cent), whereas its peer economies such as South Africa’s, with such low infrastructure deficits and world-class infrastructure have as high as 44 per cent debt to the GDP ratio and 39.30 per cent external debt component?

No doubt, the 2017 budget’s N2.36tn deficit having N1.067tn (46 per cent) external borrowing is a reverse from the past where externally borrowing accounted for less than five per cent (in some cases 0 per cent),which is a welcome development. But, then, with close to 40 per cent government revenues spent mostly on domestic debt service — and N1.66tn this year alone, what other solutions do we have than Quantitative Easing, printing enough naira to buy back our domestic debts? Or, is it not called domestic debt so that when overwhelmed in serving it, government prints the same local currency to settle it?

Why oppose QE, when as far back as 1864, President Abraham Lincoln instructed his Treasury Secretary, Portland Chase, to print $480 million (greenbacks) and use it to settle America’s huge civil war debt? And from 2009 and 2013, President Barack Obama instructed the Fed Chairman, Ben Bernanke, to print $4tn and use it to buy back corporate debts; and the EU recently used QE to inject trillions of euro into the economy paying off the Greece’s and other poor members’ domestic debts?

The false use of inflation to fiercely oppose QE, coming from the same local debt holders (mostly banks) and their top government counterparts (mostly the CBN, finance ministry and the DMO) — the same beneficiaries of the trillions spent on domestic debt — is understandable. What they are never discussing is that the same inflation is mostly imported since we import over 95 per cent of all our consumption. But are we increasing inflation by increasing the cost of borrowing? Or, can we reduce inflation without first reducing the cost of doing business which starts with reducing our huge infrastructure deficits? And should by paying off our huge domestic debts the trillions saved then be channelled into infrastructure spending?

Also, with our low national debt, why is government not aggressively borrowing externally? Given how much creditworthy we’re externally, shouldn’t we be comfortably borrowing as high as 60 per cent of our GDP externally? At about two per cent and 25 years maturity, external debts are not only far cheaper, concessionary and easy to refinance than domestic debts. Also, not crowding out real sector firms from the domestic debt market makes most domestic liquidity cheaply available at low interest rates.

Another important flaw in the 2017 proposed budget is the fact that most government departments and agencies have been operating without boards of directors. With this, it is most unlikely that the National Assembly will entertain their respective budgetary spending. This is because the law clearly states that the budget estimates of all government departments and agencies should pass through their respective boards of directors, who should approved them before they get to the National Assembly for final scrutiny and approval.

Given that the boards of most of these departments and agencies disbanded July 2015 by President Buhari have yet to be reconstituted, then, the question the respective committees of both the Senate and the House of Representatives should be asking them when they come to defend their respective budgets is: Which board directors approved their budget estimates before they were submitted to the National Assembly? The follow-up question also becomes: Which board of directors will make sure that the appropriated funds in the 2017 budget are properly spent?

The announcement that with effect from January 2017 the Federal Government will stop meeting its Joint Venture cash calls obligations raises a red flag. That red flag is, shouldn’t this cessation amount to withdrawing from the Joint Venture partnership which in other words means handing our shares in these JVs to the IOCs? If this is not backdoor and fraudulent sell-off of our joint venture shares for peanuts, then, what else should be?

Setting the record straight and ensuring that this doesn’t mean the much feared backdoor privatisation of important national assets, the National Assembly should put a hold on this. The respective committees should invite both the minister of state for petroleum resources and the Group Managing Director of the NNPC to a public hearing to explain to Nigerians why such a decision shouldn’t be short-changing the country.

In the case of the CBN’s exchange rate policy, the use of this policy to defraud the three tiers of government in the 2016 budget should not be allowed to also happen in the 2017 budget. In the 2016 budget, N197 was the official exchanged rate per dollar. But by June 2016 — barely a month after the 2016 was signed into law — the CBN floated the naira by allowing market forces to determine the actual value of the naira.

With this, the naira nosedived, quickly reaching N300 per dollar in the interbank forex market. The CBN refused to allow the same market forces to determine the official exchange rate. By handing the three tiers of government N197 per dollar when at the interbank market, N300, the CBN defrauded them N103 per dollar.

At N305 official rate, what happens if in 2017 the rate becomes N450 per dollar? Should that mean that rather than give the three tiers of government their extra N145 per dollar, the CBN will also defraud these cash-strapped tiers of government the extra revenues they badly need?

Making sure this fraud is not continued in 2017, the state governors should, during the next National Economic Council, insist on either having been handed their own share in dollars so that they go to the interbank market to change it into naira, or during every Federal Account Allocation Committee meeting, the prevailing interbank forex rate is used in the CBN’s monetisation.

Another flaw in the 2017 proposed budget is the fact that the price of oil is benchmarked at $42.50 per barrel. It is important to fully interrogate this because at a time of recession like this, all avenues to increase government revenues should be stretched as far as they can go. My insistence that benchmarking oil price at $42.50 per barrel should be increased to $50 per barrel is based on the fact that in 2017, oil price should be expected to rise as high as $65 per barrel.

Enwegbara, a development economist, wrote in from Abuja

My reasons are obvious.

First, one reason Vladmir Putin supported Donald Trump in 2016 presidential election is for him to help reverse oil prices upward, possibly close to what it was in 2013 before the US-led West to punish Russia for invading Ukraine manipulated it down. And that Trump is signalling to do that is explained by appointing Mr. Rex Tillerson, the ExxonMobil CEO as his Secretary of State.

Second, like Putin, Trump too would like to see oil prices upward for the simple reason that high oil prices is needed if his government should be able to raise the trillions of dollars to be injected into improving America’s infrastructure. It is a welcome development because if huge American infrastructure spending happens, that would result in a global economic growth.

END

Be the first to comment