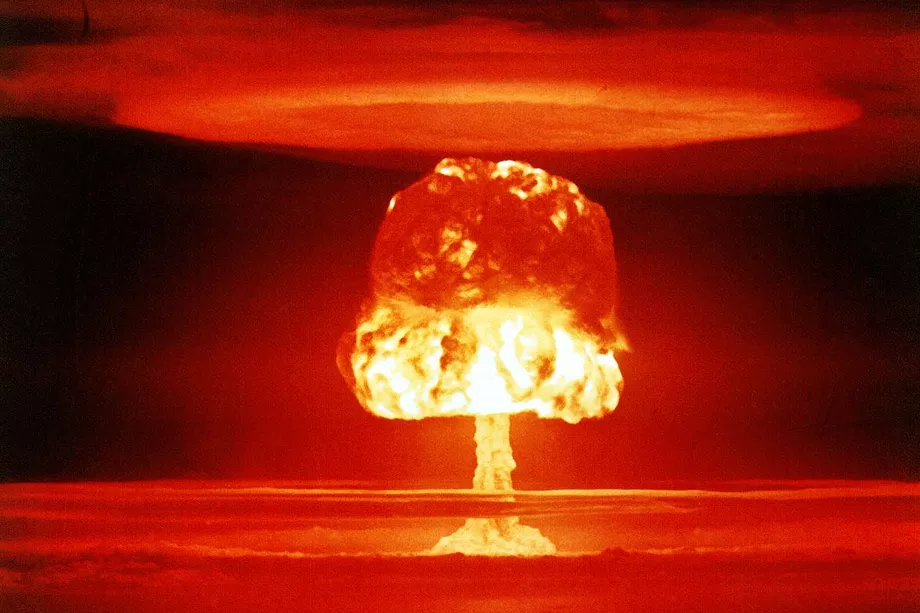

When President-elect Donald Trump officially becomes the president of the United States in January, he will take complete control of America’s nuclear arsenal. Should he decide to start a nuclear war, there are no legal safeguards to stop him. Instead, a much less tangible web of norms, taboos, and fears has reined in US presidents since World War II. But as North Korea escalates its nuclear weapons tests and the president-elect of the United States openly contemplates using nukes, experts worry that this fragile web could start to tear.

During his campaign, Trump called nuclear proliferation the “biggest problem” in the world. But he also said that Japan and South Korea might want to get nukes of their own. He wouldn’t take nuking ISIS, or even Europe, off the table. But he’s also characterized himself as “highly, highly, highly, highly unlikely” to ever use nuclear weapons. This calculated ambiguity isn’t unusual for America’s presidents. Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush left nuclear first strikes on the table, too.

But for a US president to talk so openly and frequently about using nuclear force is a clear break with history, says Frank Sauer, an international security researcher at the Bundeswehr University Munich and author of the book Atomic Anxiety: Deterrence, Taboo and the Non-Use of U.S. Nuclear Weapons. And it could be potently destabilizing in a world where nations’ nuclear doctrines are shaped more by posture than by policy.

Despite a few close calls, nuclear warheads haven’t been used in armed conflict for more than 70 years. But there’s controversy over the reason why. Robert McNamara, the US secretary of defense during the Cuban Missile Crisis, put it down to pure luck.

But Nina Tannenwald, director of international relations at Brown University, argues that a taboo gradually emerged from the nuclear devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This taboo created the shared expectation that using nuclear weapons again would be deeply, morally wrong. International relations professor and author of The Tradition of Non-Use of Nuclear Weapons, T.V. Paul disagrees, arguing that it’s not a taboo but a tradition that’s driven by social and political pressures. And underlying both of these explanations is humankind’s deep-seated fear of going extinct, Sauer says.

While mutually assured destruction — the notion that any country launching nukes would likely also be destroyed by nukes — gets the most ink in terms of deterrence, these cultural and psychological deterrents play powerful roles.

Let’s be very clear: the president alone controls the nukes. There aren’t more checks and balances because our nuclear chain of command was built to speedily deliver mutually assured destruction. In fact, the only real check on the president’s nuclear authority is the election, writes nuclear history professor Alex Wellerstein in a recent blog post. “[D]on’t elect people you don’t trust with the unilateral authority to use nuclear weapons.”

That’s because if the US is attacked, time is precious: early warning teams only have three minutes to determine whether warnings of a missile attack are real. If it looks legitimate enough to take to the president, the president then has less than 12 minutes to open the nuclear briefcase (or “football”), review his tactical options, and authorize a nuclear strike. Or at least, 12 minutes is how long the White House has if a submarine deployed in the Western Atlantic were to fire on DC; if Russia were to launch a nuke from within its borders, there’s maybe 18 additional minutes to react. If the president hesitates, a nuke could hit the White House before the US has a chance to launch a counterstrike.

Still, many experts agree that mutually assured destruction can’t fully explain why no one is using their nukes. After all, the US didn’t use nuclear weapons against Iraq in the 1991 Gulf War, even though Iraq didn’t have any nuclear weapons to retaliate with.

Theverge

END

Be the first to comment