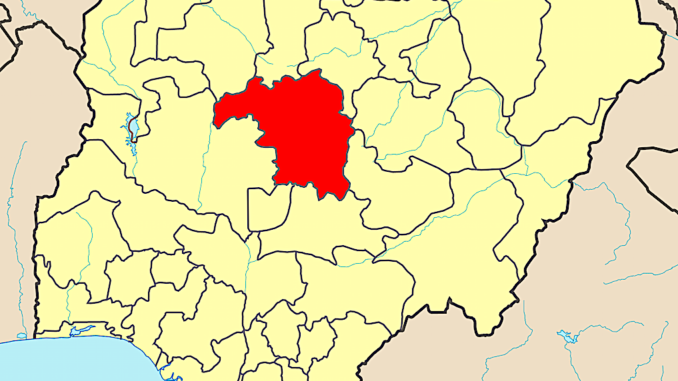

Kaduna State is a microcosm of Nigeria. Following thirty years of a fissiparous process of state creation, the political map of majorities and minorities has been complexified by the creation of numerous new majorities and minorities. The Kaduna question is about the state-wide majority versus the southern Kaduna majority.

On Tuesday, Governor Nasir El-Rufai addressed a high-powered meeting on the violent crisis in parts of southern Kaduna. He expressed sadness at the needless pain several communities have been enduring in the cycle of violence that has been recurring in the State. He outlined government’s engagement in seeking to improve the security situation in Kaduna State. A forward operating base of the Nigerian Army has been established in Kafanchan, where a permanent mobile police squadron has been set up as well. Kaduna State has also established the Kaduna State Peace Commission to engage communities and nudge them towards accord and conciliation, which are better alternatives to violence. These initiatives have not succeeded in making a difference to the cyclical violence in the area.

The current cycle of violence started in early June by youth groups from two communities clashing over farmlands in Zangon-Kataf and this quickly spread to cover four local government areas in southern Kaduna. The State government has decided, following the current crisis, to address lingering issues from the 1992 crisis in Zangon-Kataf by producing a White Paper on the recommendations made by the Cudjoe Judicial Commission of Inquiry and the Reconciliation Committee that worked on the matter almost two decades ago.

The last major cycle of violence in Southern Kaduna was in 2016/2017. I had joined a Nigerian Bar Association Fact Finding Mission in January 2017 to seek better understanding on the recurrence of the violence over such a long time, and to explore avenues for ending the violence and bringing peace back to the State. We had visited the governor at the time and he explained that the cyclical violence has affected the State for 35 years then, and over this period, between 10,000 and 20,000 people have lost their lives in the various crises that have rocked Kaduna State since 1980. El-Rufai explained that the root cause of the persistence of cyclical violence has been the lack of accountability, as no one ever gets punished for killing and harming others. The only exception, according to the governor, was the Justice Benedict Okadigbo Tribunal on the Zango-Kataf Religious Crisis of 1992, when former military president, General Ibrahim Babangida established the Tribunal to investigate those implicated in that crisis and ensure that they faced the law. Since then, subsequent killers have not been made to face the law.

Politics and religion have become tightly interconnected in the State over the years and violence entrepreneurs have emerged in both communities. As these killings have been on-going for forty years, there is enough memory of hate, hurt, reprisals and revenge to keep it going.

We live in the age of the social media, so such killings are immediately reported and spread – often with loads of gory photographs of hacked and mutilated bodies. Some of the photos are true, others fake and both are instrumentalised to create maximum emotions of fear, anger and inspire the need for revenge which keeps the cycles of violence active. As this happens, events are often amplified, exaggerated and placed within the context of narratives of hegemony, domination and discrimination. The history and the long memories of conflict between northern and southern Kaduna starting from the trans-Saharan slave raids to the political control of the zone by Zaria Emirate under colonial rule, through to military rule, always come up. This narrative of the long history of war and subjugation is then projected into the coming envisaged outcome of Armageddon and genocide. The perpetrators of the genocide are said to be Hausa-Fulani Muslims, while the victims are Christian indigenes. The reality is more complex. The killings go both ways. Maybe the largest massacre in Southern Kaduna was that of Hausa-Fulani Muslims, following the post-election violence of 2011.

Politics and religion have become tightly interconnected in the State over the years and violence entrepreneurs have emerged in both communities. As these killings have been on-going for forty years, there is enough memory of hate, hurt, reprisals and revenge to keep it going. One of the difficulties of accountability for the killings is the question of how far back one can go. If today the decision is to find and punish the killers of 2020, then the question is what of those of 2017, of 2015, of 2011 and so on. There have been about forty major incidents spread over forty years to seek accountability on. There has to be a consensus on where to draw the line. The narratives of the two communities about who is the perpetrator and who is the victim is diametrically opposed with each side seeing itself as the victim. The situation is delicate and needs a lot of caution.

Kaduna State is a microcosm of Nigeria. Following thirty years of a fissiparous process of state creation, the political map of majorities and minorities has been complexified by the creation of numerous new majorities and minorities. The Kaduna question is about the state-wide majority versus the southern Kaduna majority. The State, and indeed the country, has been going through an active process of proving that your neighbours are historically, ethnically, linguistically, culturally and religiously different from you, which is the basis for mobilising your own access to power. As the positioning evolves, hitherto peace-loving neighbours in the state or local government had to be portrayed as the terrible/aggressive/settler ‘other’ who must be separated from ‘our people’ in the interest of peace, stability, good government and development. As this type of dynamics unfolds, traditional conflict resolution mechanisms break down and ethno-regional political actors feel obliged to take maximalist positions and treat both their neighbours and the spirit of compromise with disdain. In the process, each group develops a reading of Nigerian history in which they discover that they have had the worst deal in the political equation.

I am old fashioned, so my recommendation is to go back to the original nationalist project, but that would require substantive improvement of the quality of both our democracy and our federalism. This would be no easy task but as all political scientists know, no one ever taught us that building a nation is easy.

The second issue relates to the impact of the rise of religiosity on democratic political culture. The most significant sociological variable in Nigeria over the past thirty years is the astronomical growth of the level of religiosity in society. Growth is expressed both in the intensity of belief and in the expansion of time, resources and efforts devoted to religious practice. Religious practices have not, surprisingly, as is popularly assumed, been subjected excessively to political instrumentalisation by the political elite. The Nigerian religious sphere is developing in a specific cultural context. The norms and practices of the growing number of religious movements and their activism is characterised by norms that are often antithetical to democratic ones. They include unquestioning faith on religious leaders, sectarianism and exclusiveness, intolerance and a propensity to hate speech and undemocratic organisational practices. Not surprisingly, the relationship between the trajectories of religious pluralism and democratic culture in Kaduna State, and in Nigeria, has tended to work against each other.

It is trite to say it, but so many of our nationalists have said repeatedly that Nigeria is a multi-religious, multi-ethnic and multi-cultural society, which should accept differences among its peoples and develop a large consensus of agreeing to live together. On this premise, they developed a Nigerian project – that the recipe for living peacefully together in spite of our differences, is to develop “true” federalism and “true” democracy in our society. We have not been successful on both counts. The consequence is that ethnic and religious violent conflicts are overwhelming the Nigerian state.

It was in this context that the Nigerian counter-project emerged. Its premise is that we never agreed to the amalgamation of 1914 and, in any case, after one hundred years, the amalgamation treaty has expired. (As an aside, I have never understood the logic of the second part of the argument – its either we agreed or we did not agree, so I don’t know where the hundred years came from). However, we are now being told that the time has come to negotiate a new deal in a conference of ethnic nationalities. All attempts towards this counter-project have failed woefully for the simple reason that the largest groups in Nigeria are not the WAZOBIA and other minorities, but Christianity and Islam both of which are playing a zero-sum game. This is true for Kaduna State, it is even more true for Nigeria. I am old fashioned, so my recommendation is to go back to the original nationalist project, but that would require substantive improvement of the quality of both our democracy and our federalism. This would be no easy task but as all political scientists know, no one ever taught us that building a nation is easy.

A professor of Political Science and development consultant/expert, Jibrin Ibrahim is a Senior Fellow of the Centre for Democracy and Development, and Chair of the Editorial Board of PREMIUM TIMES.

END

Be the first to comment