I asked the supervisor if there was a problem. The supervisor informed me that my passport was a “Category C” passport. That was the lowest in the hierarchy. I was shocked to find out that the second poorest country in Central America considered the Nigerian passport a third class passport. I said to myself: Yup, Nigeria has followed me here!

I went to Honduras for a 10-day vacation in April 2018. It was a reward to myself for having completed a new book manuscript. The semester’s work was over; papers were marked and grades posted. I flew from Edmonton to Minnesota and onto Atlanta from where I boarded a flight to San Pedro Sula, Honduras.

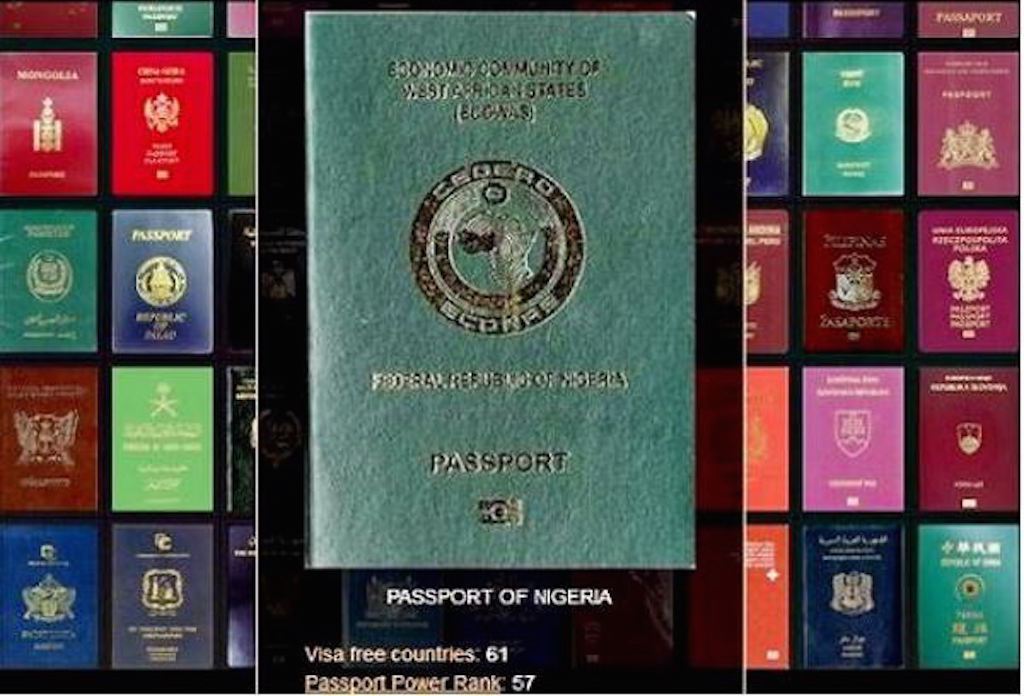

We arrived San Pedro Sula and I approached the immigration desk with my passport. The immigration officer quickly became engrossed in a forensic evaluation of my passport. She flipped through all the pages. She concentrated on a US visa in the passport. I was not sure of her English language competence, as this was a Spanish-speaking country but she kept giving hand or facial gestures. She took my passport to her supervisor after several minutes. The supervisor beckoned to me. I asked the supervisor if there was a problem. The supervisor informed me that my passport was a “Category C” passport. That was the lowest in the hierarchy. I was shocked to find out that the second poorest country in Central America considered the Nigerian passport a third class passport. I said to myself: Yup, Nigeria has followed me here!

The supervisor, however, said given that I had a (10-year) U.S. visa, I was considered “category B” but I still needed a Honduran visa, which would usually not be denied. The whole issue was a basic error due to a combination of impatience on the part of the first immigration officer and language impediment. The Honduran visa was in fact there and I showed her. The supervisor looked at it and went to the overall boss. By now, I had been there for nearly 20 minutes. Others breezed through much faster. Nope. This was not racial profiling; this was passport profiling. I noticed that all my co-travelers from the first class cabin had all left. It was a little embarrassing but I took it well with a smile that I almost forgot I had. The overall boss on duty gave the green light. My passport was stamped and I heard “welcome to Honduras”.

Two Honduran friends were on hand to pick me up at the airport. We exchanged pleasantries and began the short drive to the hotel. A young medical student was at the wheels. I realised within a few minutes that she had the mysterious skills of a seasoned Lagos driver. I had to remind myself that this was Honduras. I assured her through an interpreter that she would make a fine driver in Lagos.

What is it about people in developing countries and preference for the foreign? Perhaps some of us are in denial about the facticity of fusion of the global and the local. Perhaps nothing is local anymore. I hung on to my huge coconut and sipped water from one of the few things that were natural and untrammeled by the forces of globalisation.

Honduras is a prototypic third world country. There were evidently malnourished children begging on the streets in which people drove state-of-the-art vehicles. One man held his lame son in traffic to beg for alms while numerous men on wheelchairs took strategic positions at major intersections. Several mothers also held their babies begging for money. There was a young girl, who was cleaning windshields of cars at one of the intersections. It was a foretaste of gender “equality” in Honduras.

Then there was the unusual phenomenon of a dead horse by the roadside on the outskirts of San Pedro Sula. That was new. There were many horses grazing seemingly unsupervised by the roadside. The horses knew their way home and drivers were generally polite to them. The closest I had come to that was the confidence of cows on the streets of Agra near the Taj Mahal in India. The cows were important and they knew it.

The globalisation thing may choke us all with an unbeknownst homogeneity. My mind is not yet made up about how to evaluate that. Major North American brands were visible: Denny’s, KFC, and Popeye; and designer outlets, among others. The television stations were also full of advertisements for the Spanish iteration of “Keeping up with the Kardashians”. Really? In Honduras? Someone in our group suggested having dinner at an American restaurant. I politely informed the group (all Honduran) that I did not travel to Honduras in order to enjoy American food. I would like to have Honduran cuisine. We went to Galerías del Valle, a mall, during the weekend to watch a movie. Most of the movies were Hollywood movies. What is it about people in developing countries and preference for the foreign? Perhaps some of us are in denial about the facticity of fusion of the global and the local. Perhaps nothing is local anymore. I hung on to my huge coconut and sipped water from one of the few things that were natural and untrammeled by the forces of globalisation.

foraminifera

We went to Santa Cruz De Yojoa just over an hour away from San Pedro Sula to observe nature and have a seafood meal. We beheld an evening spectacle — sunset in Honduras. It was breathtaking. There were cows grazing and drinking in a swamp adjacent to the lake in Yojoa. They seemed to have mastered the art of not drowning despite their weight and ostensibly gently propelling themselves forward.

Infrastructure in San Pedro Sula seemed marginally better than most towns and cities I had visited in Nigeria (with few exceptions). There were no visible gaping potholes on the roads and the transportation system seemed relatively efficient and organised. I had the distinctive feeling that Nigeria was truly being left behind even by poor countries.

Honduras is plagued by street crime and its murder rate is one of the highest in the world. The political situation is also volatile. There were heavily armed soldiers seemingly everywhere. Nevertheless, Honduras is colourful and full of life. Mestizos, a mix of Amerindian and European people constitute 90 percent of the population, while Amerindians make up seven percent; and one percent is white, according to the CIA World Factbook. Honduras has an indigenous black population known as the Garifuna. They are descendants of enslaved Africans. The Garifuna make up approximately two percent of the population of Honduras. The demographic figures are interesting given that anyone who has watched a soccer match involving Honduras would assume that persons of African origins dominated the population.

The Garifuna speak the Garifuna language, a fundamentally hybrid language, which reflects the historical trajectories of the people and (largely violent) contacts with various European groups. A 2013 UNDP report notes that the Garifuna are located in 46 communities in Honduras and had lived in the Mesoamerican Caribbean coast for 214 years. The Garifuna, according to the report, have been impacted by climate change which has led to a gradual erosion of their way of life — fishing and coconut farming. It was quite a sight to behold several Garifuna persons at a resort town called Tela. The inequality in Honduras was reflected among the Garifuna.

Infrastructure in San Pedro Sula seemed marginally better than most towns and cities I had visited in Nigeria (with few exceptions). There were no visible gaping potholes on the roads and the transportation system seemed relatively efficient and organised. I had the distinctive feeling that Nigeria was truly being left behind even by poor countries.

Finally, it was time to leave after nearly two weeks. It was a wonderful learning experience. The memories of the salsa and bachata songs, as well as the seafood cuisine will last for a while.

Follow ‘Tope Oriola on Twitter: @topeoriola

PremiumTimes

END

Be the first to comment