I was in my fifth year in secondary school when one day I walked up to the noticeboard just in front of the dining hall and saw something that struck me hard.

It was a photocopy of an advert by MD Yusufu, candidate for president set to run against military ruler, Abacha in the 1998 elections. The ad was a response to the General’s ‘Whom the cap fits’ ad campaign. Our proprietress – a warrior herself, Sheila Solarin – had made it a point of duty to update the students on what was happening with Abacha wanting to become a democratic president.

I had grown up to know Nigeria as a country with no soul, no principles, and no heroes. The only man that came close to heroism, in my space of limited history, had been dispatched to jail after winning an election in 1993, and kept there.

His friends had abandoned him, joining the government of the man that jailed him, or even helping him steal the mandate their man had won.

Those who were brave at all were curiously in exile, far away from the scene of danger. The rest of the country had coalesced around the ‘five fingers of one leprous hand’, five parties begging one man to run for office – with the man who would be president intimidating anyone else who was thinking of challenging him.

It was a terrible time to be a Nigerian, and an even worse time to hope.

Of course, there where patriots – those like Beko Ransome-Kuti, Chima Ubani, Kunle Ajibade and others – who were fighting the despot to something of a standstill. But in politics there was no one. Abacha was about to get an easy ride into civilian office.

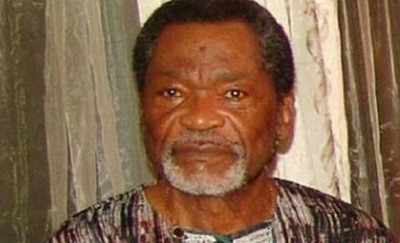

Then suddenly, from what seemed to this 13 year old like nowhere, came the duo of MD Yusufu and Tunji Braithwaite. With their parties, the Grassroots Democratic Movement and the Nigerian Advance Party, they decided to wage war against Abacha.

It was such a breath of fresh air. Running as presidential candidates of their parties in a time when no one dared to do, they put themselves directly in the line of fire, not just by that singular act of defiance, but by waging a vigorous media attack against the dictator.

They took out pages in newspapers to mount protests via dramatic full page ads; they went on what television they could afford to go on and spoke against him with heart and gusto; they blanketed the pages of the Vanguard andThe Guardian that I read whenever and wherever they could, denouncing the collusion of the cowardly; they held press conferences and said all that they possibly could with anger and vehemence, resolutely slashing the spiral of elite silence that threatened to strangle Nigeria.

I adored them.

They made it possible for me to see another Nigeria, and to see its leaders in another light. That it was possible to speak truth to power, even at risk of life. That men remained who could choose honour over collusion, and dignity over the proximity to power.

They taught me that there is always another way. It might be unpopular and dangerous. But it exists. And no one has the excuse to claim fear or doubt when they can stand up to be counted.

They brought those remarkable stories of Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King home to me – so that I believed that the Nigerian blood that flowed in my veins and around me had as much possibilities to be true and to be fearless as the best of the world’s.

They made me feel proud to be Nigerian, and proud of other Nigerians. They taught me about a place called Courage.

The rest of their lives didn’t continue in a straight line, of course. Sometimes they made questionable choices as politicians are wont to do.

But one of the tragedies of our inchoate cultural march is that very few young people know the complete and nuanced histories that they should.

Because if we knew what we should then we would be grateful for these men (and women) who demonstrated the kind of courage you thought you would find only in fiction. Who fought when the risks were much more than losing followers on Twitter; and who stepped on the streets when the risk was the attack of bullets.

If we knew more and we knew it right, we would celebrate and honour them more extensively, we would learn the lessons of their lives, and – to honour their sacrifice – we would do much more than the pitiable resistance that we presently put up to those who put our nation, and its future, at sore risk.

MD Yusufu used to sign off his heroic ads with copy that struck deep with my soul, “May God give us the will and the way to act”.

As he and Mr. Braithwaite take their bows in honour, in dignity and in glory, almost exactly within a year of each other, and as I thank them most deeply for showing us the way and the truth, one can only hope that their prayers are answered.

For this generation. And the next.

PREMIUM TIMES

END

Be the first to comment