•What was life like before email — electronic mail?

Persons born in 2000 and later cannot even conceive it. Those born in the last two decades of the 20th Century, the so-called dot.com generation, can recall only dimly some aspects of social life and business transactions before email came along.

They remember “snail mail,” the material you transmit through the post office, which is still with us. Older persons will of course remember the telegram, and the telex which, until email came along, were the fastest means for conducting urgent communications.

But in these parts, you had to go to the post office to send your telegram, and to the less accessible telecommunications office to send your telex. The telegram was transmitted by telephone to the nearest postal centre for delivery to the addressee. If there was no post office where the receiver lives, delivery could take several days. The telex was faster and less cumbersome. But, as with the telegram, point-to-point delivery was not assured.

Electronic mail changed all that.

It eliminated distance and physical barriers and rendered time immaterial. You type your message, you hit the “send” button, and in an instant it bobs up on the recipient’s computer screen next door or half a world away. You can send that same message to hundreds, even thousands, by the simple expedient to typing in their addresses, unlike in the past when you had to send a paper copy to each addressee.

You can attach documents of every description. You can attach pictures, architectural drawing, sketches, musical compositions, and video. You can do all this and much more at a fraction of the cost of transmitting it by the old traditional mail. You can store your email and retrieve it just as easily.

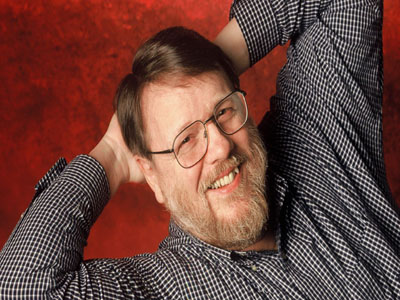

The world owes this technological device that has transformed the way we live and relate and create and do business to the electronics research and development engineer Ray Tomlinson who died last week in Cambridge, Massachusetts, aged 74.

Electronic mail was not Tomlinson’s first epochal achievement, however. He had become a cult figure since 1971 when he invented a programme for ARPANET, the Internet’s predecessor that enabled people to send person-to-person messages to other computer users on other servers.

Like many inventions that have revolutionised our world, email was a product of chance, an accident as it were. Tomlinson was “just fooling around, “according to a 1989 profile in Forbes magazine, looking for something to do with ARPANET when he stumbled upon it. His first message was to two machines placed side by side.

When the message went through, he reportedly pleaded with a colleague, “Don’t tell anyone! This isn’t what we’re supposed to be working on.”It was only when he was satisfied that the programme really worked that he announced it by sending a message to co-workers explaining how it could be used.

At the time, few people had personal computers. The use of personal email would not reach high numbers until years later. Today, it is an indispensable part of modern life.

Sadly, it is not always used for beneficent ends. It is daily employed to spread falsehood, to promote hatred, to disseminate pornography, and to perpetrate extortion on a grand scale. There are no obvious cures for these perversions, and no foolproof answers.

These unintended and unfortunate consequences represent the price society pays for breakthroughs that help improve the quality of social life. Without question, email constitutes one such breakthrough.

According to philosophers of science, revolutionary breakthroughs, the type emblematized by email and the Internet, come after long intervals. Scientific and technological advancement generally occur by accretion, in small, incremental steps, while huge leaps manifest only once in a while.

Are our universities and research laboratories equipped to do the kind of work that can lead to the next scientific breakthrough of global significance and thus establish Nigeria as a crucible of innovation?

This question should guide those who make and administer educational policies and disburse funding for research in Nigeria.

END

Be the first to comment