Parents should not worry about their teenagers’ delinquent behaviour provided they were well behaved in their earlier childhood, according to researchers behind a study that suggests those who offend throughout their life showed antisocial behaviour from a young age and have a markedly different brain structure as adults.

According to figures from the Ministry of Justice, 24% of males in England and Wales aged 10–52 in 2006 had a conviction, compared with 6% of females. Previous work has shown that crime rises in adolescence and young adulthood but that most perpetrators go on to become law-abiding adults, with only a minority – under 10% of the general population – continuing to offend throughout their life.

Such trends underpin many modern criminal justice strategies, including in the UK where police can use their discretion as to whether to a young offender should enter the formal justice system.

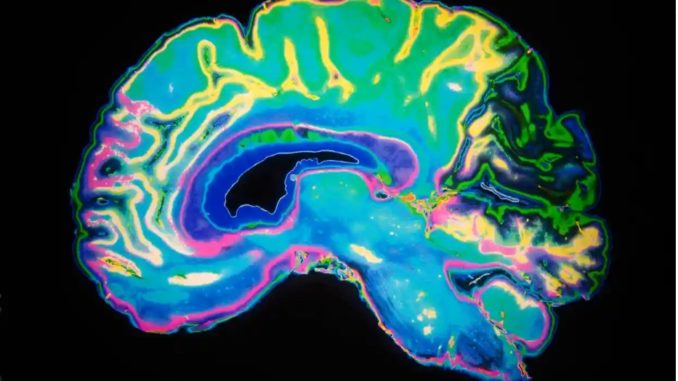

Now researchers say they have found that adults with a long history of offences show striking differences in brain structure compared with those who have stuck to the straight and narrow or who transgressed only as adolescents.

“These findings underscore prior research that really highlights that there are different types of young offenders – they are not all the same. They should not all be treated the same,” said Prof Essi Viding, a co-author of the study from University College London.

Prof Terrie Moffitt, another co-author of the research from Duke University in North Carolina, said the study helped to shed light on what may be behind persistent antisocial behaviour.

“It could have been just that the life-course-persistent group were choosing to lead their lives in a difficult way and could have chosen differently. I think that what we see with these data is that they are actually operating under some handicap at the level of the brain,” she said, adding that while such individuals may have committed serious crimes, the study suggested a level of compassion was needed.

The team say the findings suggest more needs to be done to identify children who show signs of ongoing antisocial behaviour and to offer them or their parents support – a move they say could reduce crime later on.

Prof Huw Williams, a clinical neuropsychologist at the University of Exeter, who was not involved in the study, stressed it was not set in stone that a child with antisocial behaviour would go on to become a persistent offender.

“This [study] reinforces the need to help children and young people who have trouble ‘self-regulating’ to get help at the earliest opportunity to reduce risk of escalation of behaviour,” he said, suggesting one approach would be a boost in support available through schools.

Writing in the journal Lancet Psychiatry, the team report how they used data from 672 people in New Zealand born in 1972-73. Detailed records of participants’ antisocial behaviour were collected at regular intervals from the age of seven up until the age of 26 . At age 45, participants had their brains scanned.

The team split the participants into three groups based on their history of antisocial behaviour: 441 showed little sign of such behaviour, 151 were only antisocial as adolescents and 80 displayed antisocial behaviour from childhood onwards.

The latter group had higher levels of mental ill-health, drug use and had more deprived backgrounds than those in the other groups. What’s more, their antisocial or criminal behaviour was generally more violent than for adolescent-only delinquents.

The team found brain scans of adults who had a long history of offending showed a smaller surface area in many regions of the brain compared with those with a clean track record. They also had thinner grey matter in regions linked to regulation of emotions, motivation and control of behaviour – aspects of behaviour they are known to have struggled with. The team say the findings remained even when other factors such as IQ and socioeconomic status were taken into account.

Those who had been delinquent only as adolescents also showed some differences in the average thickness of grey matter compared with the law-abiders, but no difference in surface area.

However, the picture of cause and effect for the persistent offenders is far from clear. The team say genetic and environmental factors – such as childhood deprivation – may have shaped their brains early in life. It is also possible that other, later factors such as smoking, alcohol or drug abuse could have caused the brain changes.

The study has other limitations. Brain scans were taken only when the participants were adults, while only a small group showed long-term antisocial behaviour, meaning larger studies are needed to be sure the findings hold. In addition, more than 90% of the participants were white, and the team looked at only one type of brain tissue.

Williams added that the possibility of head injuries playing a role in the brain differences was not robustly considered, despite such events affecting the brain and behaviour and being more common among people of lower socioeconomic status.

Prof Kevin McConway, of the Open University, said that even if the brain differences were down to genetics or other early-life factors, it may be those factors themselves, not the resulting brain differences, that were behind persistent antisocial behaviour.

“It’s true that these research findings are consistent with the hypothesis that life-course-persistent antisocial behaviour arises as a result of abnormal brain development,” said McConway. “But observations being consistent with a hypothesis doesn’t mean that the hypothesis must be true, only that it can’t yet be ruled out.”

END

Be the first to comment