Without losing sight of the significant ground to be covered to institutionalise open contracting, my colleagues and I are encouraged by the gradual culture shift from a closed to an increasingly open system, one year at a time.

It was the early days of Nigeria’s Freedom of Information Law. My colleagues and I had written to the Universal Basic Education Commission (UBEC) requesting for their procurement records. We informed them that we would like to have it in seven days in accordance with the law. Like several public institutions who at the time knew very little about the sunshine legislation that provided everyone access to publicly held records, we got a rather harsh response from UBEC to the effect that they were not obliged to provide us with their procurement records. Naturally, we were upset that our request was turned down because we were eager to discover the outcomes of contracts awarded for providing free universal basic education. But we could not do this without sufficient information linking the contract award process to the outcomes from the executed contracts. And so we sought a remedy from the courts and also tried to get the National Human Rights Commission to act on the violation of our right to information. When UBEC was served with the court papers, they requested for us to meet and try to settle out of court. They asked that the case be withdrawn and we said it would be done once our request for information was granted. That was the start of a long, collaborative and sometimes contentious engagement with UBEC.

The Paper Trail

UBEC is one of the many public institutions from which we constantly seek procurement records. In 2013, for example, we sought procurement information from at least 15 institutions; 67 institutions in 2014, 116 institutions in 2015; and 131 public institutions in 2016. However, UBEC receives many more procurement requests from us because basic education policy and practice, which is overseen by UBEC, is one of our areas of priority. Our focus on basic education is no surprise and we are only one of many institutions with this focus. Its importance is reflected in the two percent of Nigeria’s consolidated revenue, which is set aside annually to guarantee free universal basic education to all Nigerians who require it, from early childhood to junior secondary school. The basic education sector is also the recipient of significant development aid assistance; from indigenous community contributions to international funding organisations.

To our numerous requests for information, UBEC often provided printed copies of their procurement plans and details of capital expenditure, but the data provided was never really enough for our purposes because we desperately needed various stages of the contracting data to speak to each other. We needed to be certain that a certain budget estimate for an Al-Majiri school, for example, resulted in a specific contract award and was the contract being executed in a specific location. That was the only way we could accurately trace the performance of the contract, and eventually, the impact of the executed contract in realising free, universal basic education to beneficiaries.

Our constant requests for information became a huge administrative burden to UBEC and after a while, the requests were once again ignored. Through the persistence of Margaret Azuibike, our independent monitor assigned to UBEC, we eventually got some more information that enabled us make better sense of the various contracting processes undertaken to provide basic education.

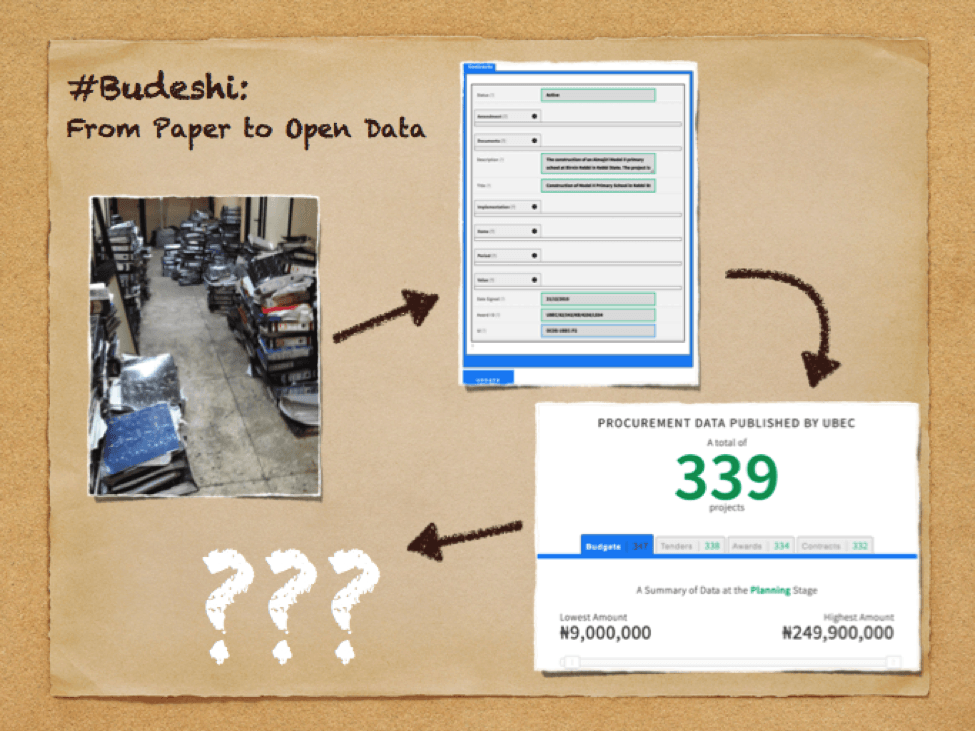

It soon became obvious to us and to UBEC that things needed to be done differently as the current system for making FOI requests for procurement records was broken and unsustainable. It was unsustainable to keep making requests for routine information, having them compiled and delivered in hard copy, and then converting them to excel sheets. With no unique identifiers linking the various stages of the procurement data provided to executed contracts and their impact, the data was unfriendly for monitoring or tracking the outcomes of executed contracts.

To deal with these challenges, first, we intensified our advocacy to get UBEC to proactively disclose procurement records. The encouragement took different forms over a period of two years. We instituted an action in court to compel UBEC to proactively disclose their procurement records, we held meetings with them, we conducted annual rankings of their level of disclosure alongside other public institutions. In 2015, using converted data obtained from UBEC, we held public demonstrations to encourage them to adopt the open contracting data standards. Through our demonstrations, we pointed out that implementing the OCDS would not only make the data readily available, thus reducing the burden of information requests, but it would enable UBEC link the various stages of procurement data together, which would allow more robust analyses that would inform any monitoring, tracking or decision-making activities. Whilst our advocacy was ongoing, we kept receiving procurement data from UBEC on request, and linking various stages in the data together using the OCDS. In spite of the burden of providing procurement data on request, UBEC also got better at compiling the data that was provided to us and this created a form of working relationship between ourselves and UBEC.

The Directive

A golden opportunity arose to push forward our advocacy. In May, 2016 at the London Anti-corruption summit, the Nigerian Government committed to implement the OCDS in key sectors including the education sector. Relying on the statement by the Nigerian Government, we held a meeting with the former executive secretary of UBEC, Dr. Suleiman Dikko, his directors and heads of units and explained why UBEC needed to lead by example in using the OCDS to liberate procurement data and ensure that it informs decision-making. Dr. Dikko immediately gave a directive for implementation of the pilot to commence in UBEC. We did not need a second invitation. We hit the ground running.

As we worked together, it became clearer that in spite of our differences and our various approaches to realising improved access to basic education, ultimately, we wanted to improve the current procurement system and as a result, we became much more accommodating of each other.

The Road Map

Following Dr. Dikko’s directive, we worked closely with UBEC to develop a road map to pilot implementation of the OCDS and shared this with the regulators, the Bureau of Public Procurement (BPP) for input and overall oversight.

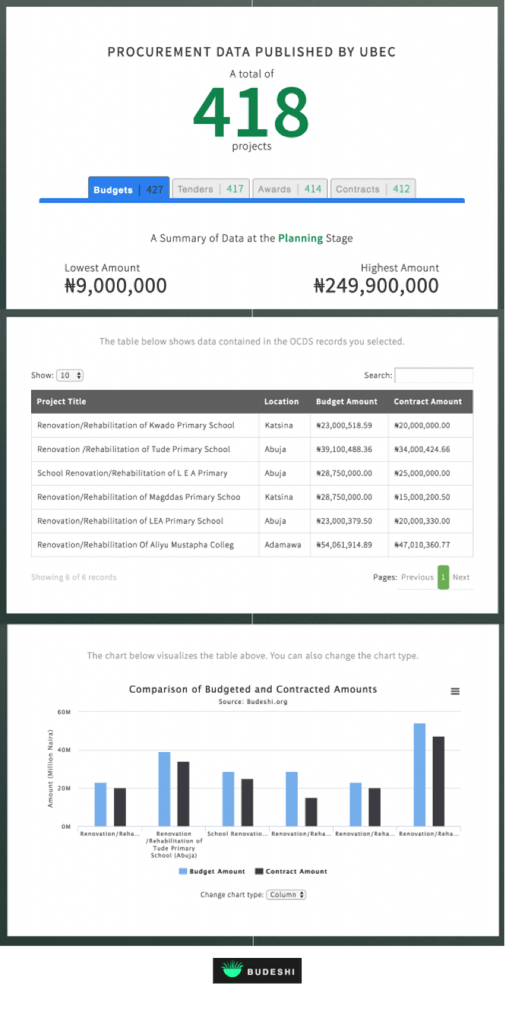

According to our roadmap, in the short term, we expect to have a living, openly accessible platform, deployed by UBEC, using public contracting data that is based on the OCDS. Our expectations at the time and at present is that the deployed platform would serve as a model for the regulators, Bureau of Public Procurement (BPP) to expand implementation of the OCDS across the public sector, that the OCDS would henceforth serve as the default method for recording and sharing procurement data. In the light of various public finance systems that collect contracting data, from budget planning to transactional level data within our government financial management information systems, the roadmap also laid out an expectation that planning and transactional level data within various public sector solutions would also map data collection, according to the OCDS requirements, so that we achieve our aim of linking data across all stages from project conception to contract award to contract implementation and delivery. Based on admonition from Tim Davies of the Open Contracting help desk, and our growing experience of the rigour of systematic data entry, we also set out an expectation for UBEC to retain high data quality at all times.

Guided by our roadmap, we carried out a scoping assessment at UBEC, a technical working group from key departments was set up, engagement and sensitisation workshops were organised for UBEC staff, technical training exercises were held and we provided support to enable UBEC convert its historical data to the OCDS. As we worked together, it became clearer that in spite of our differences and our various approaches to realising improved access to basic education, ultimately, we wanted to improve the current procurement system and as a result, we became much more accommodating of each other.

All Hands on Deck to Lead By Example

Within our road map, we also had a target to showcase the pilot of UBEC’s open contracting data to other public institutions on the September 28, 2016, to mark right to know day. Under the leadership of the Assistant Executive secretary of UBEC, Mr. Gambo, the procurement unit provided us with every support required. Mr. Ben Smart and Mr. Umar Attah from the procurement unit worked closely with my colleagues Nkem Ilo and Margaret to map available data, provide feedback on the platform development, respond to any questions we had on the procurement data provided. My colleagues, Gift and Samuel coordinated data entry by the procurement monitors, Patrick and Uzoh tweaked our open contracting platform, Budeshi, to meet UBEC’s needs and specifications, Faith, Ifeoma and Ndubuisi took charge of every administrative detail to ensure that we had a good venue for the event, that invitations went out to all public institutions.

September 28 arrived and UBEC presented a pilot of their data to other public institutions, taking time to explain the journey that led to the pilot of the OCDS on Budeshi. UBEC explained how we sued them, how the case was withdrawn, how we moved from contention to collaboration. The responses from public institutions was overwhelmingly positive. The need for effective open Government practices was emphasised by Dr. Joe Abah of the Bureau of Public Service Reforms, who without doubt, leads public service reforms by example. The call for exemplary open government leaders in the public sector was further supported by Mrs. Juliet Ibekaku, the Special Adviser to the President on Justice Reforms and several other public institutions, including officials from the security sector.

Without losing sight of the significant ground to be covered to institutionalise open contracting, my colleagues and I are encouraged by the gradual culture shift from a closed to an increasingly open system, one year at a time.

Seember Nyager advocates for the adoption and Implementation of the Open Contracting Data Standards (OCDS) across the public sector in Nigeria and in other African countries. You can follow the work of procurement monitors on twitter @ppmonitorNG.

PremiumTimes

END

Be the first to comment