he video that appeared on Tuesday morning had the appearance of history in the making. In the purple light of dawn, it showed a group of armed men and a military vehicle on a road leading to La Carlota airbase in eastern Caracas.

In the foreground, stood Juan Guaidó – the head of the national assembly recognised by most western countries as the rightful leader of Venezuela – declaring the “final phase of Operation Freedom” with oratory seemingly destined for legend.

“Today, brave soldiers, brave patriots, brave men loyal to the constitution have heard our call. We have finally met on the streets of Venezuela,” Guaidó said.

Behind him, was the country’s most prominent political prisoner, Leopoldo López who had been under house arrest since 2017. The fact that he was free as the uprising was being declared seemed proof that something significant was afoot.

We now know that there was indeed a plan designed to resolve the dangerous standoff in the country between Guaidó’s assembly and the socialist government of Nicolás Maduro, heir to Hugo Chávez’s Bolivarian revolution.

Key members of the security apparatus were to defect. (Christopher Figuera, the head of the secret police, Sebin, had already done so, springing López from house arrest.) That was supposed to be a signal to the armed forces – the key to Venezuela’s future – to flip sides.

Maduro was to fly to Cuba “in dignity”. Everyone else from his regime would keep their jobs while Guaidó became interim president, pending new elections. All of this had been put down in writing, in a 15-point document, according to officials in Washington.

But it is still far from clear whether this plan had any chance of working – or whether some of the would-be defectors were simply laying a trap.

Even if the plan was real, it was already going awry when Guaidó made his speech to camera on Tuesday.

It was a day earlier than planned. Operation Freedom was supposed to reach a climax with mass protests set for Wednesday. And in retrospect it is clear the Tuesday video had been closely cropped to mask the fact that there were only a handful of troops standing with Guaidó.

Vanessa Neumann, who was appointed Guaidó’s envoy to the UK in March, said that his camp had heard reports that Maduro had got wind of the plan and was going to arrest the national assembly president.

“The decision to go on Tuesday rather than Wednesday was an operational decision, taken in reaction to new reports from the ground that we got,” Neumann told the Guardian. “But how it unfolded – in terms of the people, the military and calling on the people to join – that was foreseen.”

The rattle of hundreds of pots and pans being banged woke Julio Bianchi on Tuesday morning. The Caracas architect thought it was yet another power cut, but his bedside light was still on. Then he looked on his phone and saw the Guaidó video.

“We knew that this could be coming, but when I saw Leopoldo [López] in the video, I had no doubt that this was it: Maduro had fallen. If Leopoldo was free this had to be big.”

Mariana Otero, a young mother of three sons, got the call from a friend who lives near La Carlota: “Come now because the base has fallen.” With a Venezuelan flag draped around her shoulders like a cape, Otero quickly headed out to join thousands of others heeding Guaidó’s call.

“If Leopoldo is out there on the streets, I should be too. I want freedom in my country. The streets are ours and I want my children to be witnesses to the way we have come out to struggle for our liberty.”

She was not alone. As she headed towards Plaza Altamira in the affluent municipality of Chacao in eastern Caracas, hundreds of people were on the street around her.

But there were fewer protesters from poor areas on the city outskirts – perhaps because of the air of uncertainty and fear spread by paramilitary groups loyal to Maduro which have snuffed out dissent in poor areas of the city.

At midday, those who had crowded into Plaza Altamira could not believe their eyes: on top of a truck in the square, a group of rifle-toting national guardsmen surrounded Guaidó as he again told the crowd that the regime had fallen.

The troops wore blue ribbons on their arms to show they had defected to the opposition; one wore a bandanna across his face. López and several members of the opposition-controlled national assembly were also there.

“Valientes, patriotas, sí se puede,” chanted the crowd. “Brave patriots! Yes we can!”

But the momentum was already disappearing. After addressing the crowd, Guaidó and his team melted away – and the crowd which had expected to march on the Miraflores presidential palace were left milling in the square.

Apart from the secret service chief, Figuera, no big names from Maduro’s government had switched sides. One by one, the big fish tweeted out vows of allegiance.

Meanwhile, in downtown Cúcuta, a Colombian border town, a group of Venezuelan army defectors watched news of the uprising in a hotel room TV.

“When we saw our President Guaidó there with our brother soldiers and Leopoldo López, now free, at his side, we immediately coordinated with troops here to see what we could do,” said one defector.

Unarmed and in civilian clothing “out of respect to Colombia”, the defectors gathered by the Simón Bolívar International Bridge that separates the two countries in hopes of an ad hoc invasion. “We were ready to take San Antonio,” one defector said, referring to the town on the Venezuelan side of the bridge. “We were just waiting for the orders to join our brothers in arms on the other side.”

That order never came. Instead, defectors say, they received an order from Guaidó’s team to return to their hotels.

“It was a great letdown,” one soldier said. “We wanted to help free Venezuela.”

In Washington, Trump administration hawks who had hailed a moment of liberation watched in consternation as the uprising fizzled.

It is far from clear whether the US communicated directly with Maduro’s circle in the buildup to Operation Freedom. López, after seeking haven in the Spanish embassy in Caracas, told journalists that the key negotiations took place at his house over the past few weeks, but the claim has been treated by sceptics as grandstanding by an aspiring president anxious not to be outshone by Guaidó.

The Trump administration reacted as if it had been personally betrayed, and took the unexpected step of going public with its version of events, saying out loud the sort of details normally kept secret.

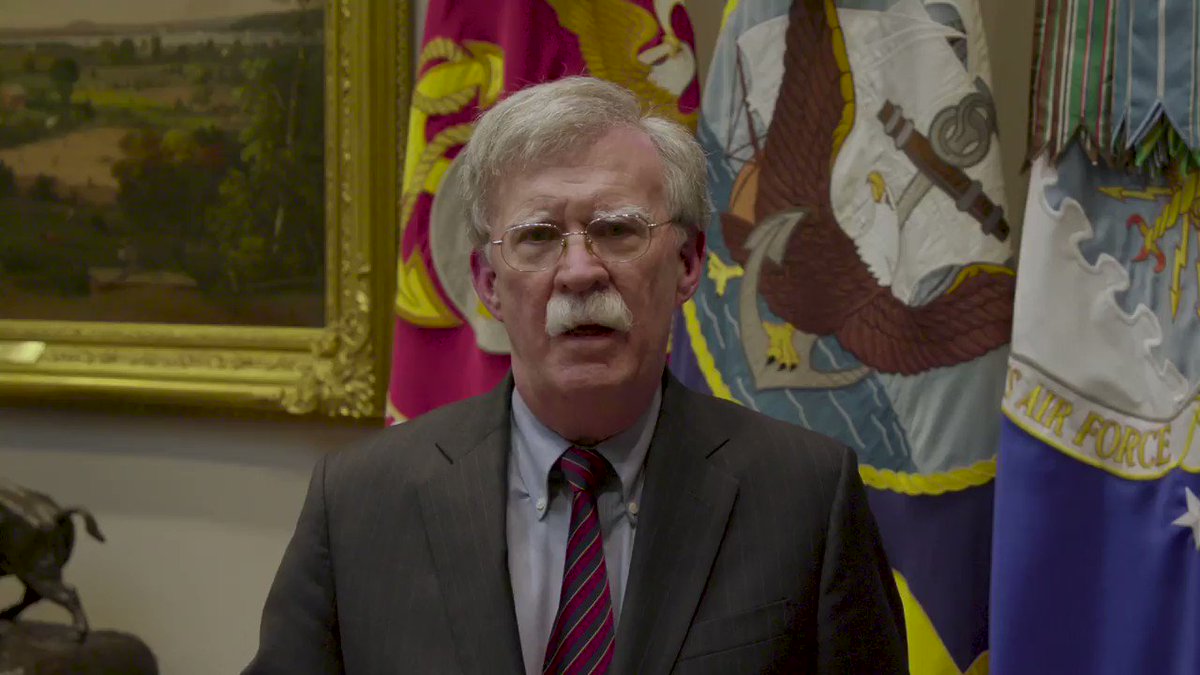

John Bolton, the national security adviser, named the three powerful Venezuelan officials he claimed had been negotiating Maduro’s departure: the defence minister and head of the armed forces, Vladimir Padrino; the chief justice of the supreme court, Maikel Moreno and Iván Hernández, the head of the presidential guard and military intelligence.

Bolton called out the men three times outside the White House – and then again in a bizarre video that was supposed to be an appeal to patriotic Venezuelans but which was entirely in English apart from the single word “libertad”.

The US secretary of state, Mike Pompeo, claimed that Maduro’s plane had been on the tarmac waiting for takeoff, but that he had been persuaded not to leave at the last moment by the Russians, a claim the Russians denied.

Donald Trump himself went on Twitter to rail against Cuban support for Maduro. And the US envoy for Venezuela, Elliott Abrams, a veteran of Reagan-era US covert operations in Latin America, appeared on a independent Venezuelan television channel, giving a detailed account of the 15-point document the defectors were supposed to have signed.

So while the official line was that the uprising was the work of the Venezuelan masses, everything the Trump administration did reinforced the message that it had been made in Washington.

“It’s idiocy. I don’t know what they think they are doing but they are undermining the efforts of the opposition to achieve their goals,” said Eva Golinger, the author of several sympathetic books about Chávez.

By Tuesday evening, Maduro staged a show of unity and strength for the television cameras surrounded by a phalanx of soldiers, with defence minister Padrino, one of the supposed defectors, at his right shoulder.

María Corina Machado, the leader of the Vente Venezuela opposition group, which openly supports the idea of foreign military intervention to unseat Maduro, admitted temporary defeat.

“Of course, the final objective was not accomplished,” she said. “Our goal was to have an urgent transition to democracy in Venezuela because this human catastrophe will only stop or start to be solved the moment Maduro and his mafia regime leaves power.”

She partly blamed drug cartels and guerrilla groups that she said represent a shadow power network within the country for the failure of the uprising.

In Washington, Bolton and Pompeo have hinted at the possibility of direct US military intervention to tip the scales to oust Maduro, but have so far been restrained by the Pentagon. The Washington Post reported a confrontation in the White House, between Bolton’s hawks and the vice-chairman of the chiefs of staff, Paul Selva.

As Selva made the case against any risky US escalation, he was repeatedly interrupted by Bolton aides demanding military options, until the normally mild-mannered air force general slammed his hand on the table, and the meeting was adjourned early.

Fulton Armstrong, a former CIA expert on Latin America now at American University said he was concerned that the generals could not hold out indefinitely against the calls for action.

Armstrong said: “These [Trump administration] guys are so desperate for a win – and with so much testosterone in their veins, I am really worried they are going to do something really stupid.”

Be the first to comment