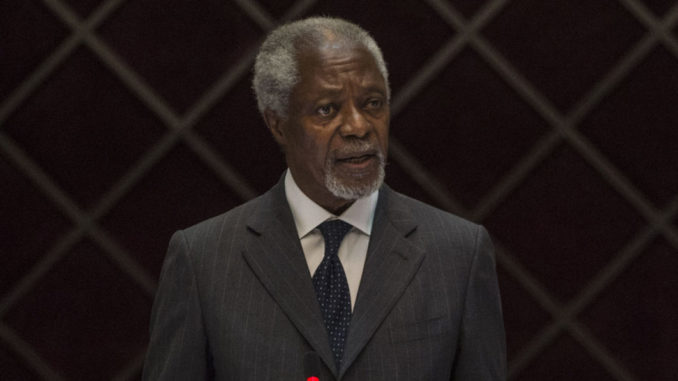

SHORTLY after he became the seventh Secretary General of the United Nations in January 1997, Ghanaian Kofi Atta Annan, who drew his last breath in a Swiss hospital on Saturday August 18, addressed members of his inner staff and a handful of journalists. He hadn’t quiet spent a month in office, and the air was palpable with goodwill and expectation. Mr. Annan took his audience by surprise when, affecting a subdued tone, he thanked them for honoring his invitation and then went ahead to apologise for not having completed the comprehensive reorganisation of the UN’s internal system that he had promised. It was only after they saw the mischievous glint in his eyes that those in the room realised that he was being sardonic.

The late Annan, who will go down as one of the most accomplished diplomats of the second half of the last century, did not consider himself above the occasional tongue-in-cheek remark. As a matter of fact, it was part of his overall bonhomie. In the authorised (and some would say, authoritative) account of Kofi Anna’s secretary generalship, New York Times contributing writer James Traub describes Annan as a “gentle, kindly African with the silver goatee and the rueful yellowing eyes;” full of “modest charm and moral gravity;” “the most gracious of men;” and someone who would “usually greet me with a big smile and a roundhouse handshake” and “rarely failed to ask after my wife, my son and my parents.”

Annan’s geniality stood out partly because it was at odds with the popular profile of a diplomat. Yet, if anything, his career demonstrated that a diplomat’s charm need not be a hindrance to his or her effectiveness. By the time he became Secretary-General in January 1997, the UN’s reputation was in the toilet. His predecessor, the Egyptian academic and diplomat, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, had caught some flak from across the international community for the UN’s alleged mishandling of key international crises, especially its perceived sluggish reaction to the Rwandan genocide. Contra Boutros-Ghali, Annan had the advantage of emerging from within the ranks of the UN and consequently exposure to ‘local knowledge’.

That he leveraged this knowledge to the hilt- and to benefit of the UN- cannot be doubted, and his ten-year tenure (1997- 2006) will be remembered as one of the most successful in the organisation’s checkered history. The following excerpts from the organisation’s website testify to the volume of Mr. Anna’s accomplishments and the high regard in which he is held within the United Nations: “At Mr. Annan’s initiative, UN peacekeeping was strengthened in ways that enabled the United Nations to cope with a rapid rise in the number of operations and personnel. It was also at Mr. Annan’s urging that, in 2005, member states established two new intergovernmental bodies: the Peacebuilding Commission and the Human Rights Council. Mr. Annan likewise played a central role in the creation of the Global Fund to fight AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria, the adoption of the UN’s first-ever counter-terrorism strategy, and the acceptance by member states of the “responsibility to protect” people from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. His “Global Compact” initiative, launched in 1999, has become the world’s largest effort to promote corporate social responsibility.”

Furthermore: “Mr. Annan undertook wide-ranging diplomatic initiatives. In 1998, he helped to ease the transition to civilian rule in Nigeria. Also that year, he visited Iraq in an effort to resolve an impasse between that country and the Security Council over compliance with resolutions involving weapons inspections and other matters—an effort that helped to avoid an outbreak of hostilities which was imminent at that time. In 1999, he was deeply involved in the process by which Timor-Leste gained independence from Indonesia. He was responsible for certifying Israel’s withdrawal from Lebanon in 2000, and in 2006, his efforts contributed to securing a cessation of hostilities between Israel and Hezbollah. Also in 2006, he mediated a settlement of the dispute between Cameroon and Nigeria over the Bakassi peninsula through implementation of the judgment of the International Court of Justice. His efforts to strengthen the organisation’s management, coherence and accountability involved major investments in training and technology, the introduction of a new whistleblower policy and financial disclosure requirements, and steps aimed at improving coordination at the country level.”

It was in acknowledgment of these prodigious achievements that Mr. Annan was awarded a share of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2001, the Stockholm-based organisation citing his (and the UN’s) “work for a better organised and more peaceful world.” After his tenure as Secretary-General, Mr. Annan, often with his Swedish-born wife Nane Maria Annan alongside, did not relent in his work as an international troubleshooter, mediating in the troubled political process in Kenya and Sudan, for instance. His death leaves a big vacuum in the world of international diplomacy.

END

Be the first to comment