As part of efforts to monitor fiscal sustainability, the PBO would develop a multi-year framework to analyse spending, performance and relative operational efficacy using public performance and spending data. The FAA would also ensure that all of government’s programmes are effective and efficient, focusing on results, value for taxpayers’ money, and aligned with current priorities and responsibilities.

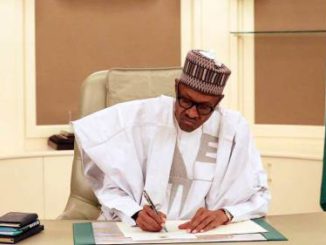

There are indications that the impasse between the National Assembly and the Presidency in respect of President Muhammadu Buhari’s 2016-2018 External Borrowing Rolling Plan request of $29.96 billion would soon be resolved. Sources close to both sides have hinted at a possible representation of a detailed request by the president and a commitment on the part of the legislators to granting speedy approval. The president had on November 1, 2016 forwarded a request to the National Assembly seeking for the approval of an external borrowing plan that would be used to address the infrastructure deficit in the health, education, water resources and other sectors. According to President Buhari, the projects and programmes under the external borrowing plan were selected on the basis of positive technical economic evaluations, as well as the contributions they would make to the socio-economic development of the country, including employment generation, poverty reduction, and protection of the nation’s vulnerable population.

In the last two weeks, several arguments have ensued in the public space over this issue, with some in full support of the president’s move, and others opposing it. The proponents have argued that the intentions of government as captured in the borrowing plan are vital to not just taking the economy out of the woods (recession) but also to ensuring sustainable growth. Opponents have however argued that borrowing $30 billion within a three year period to fund the nation’s budget and huge infrastructural deficits is not the way to go, particularly considering that our total debt stock since the debt relief in 2006 has been under $20 billion. To the latter, the argument that the country’s current debt to GDP ratio is minimal at 13.5 percent, therefore, making room for additional loan, holds no water, as “ratios were made for normal and productive economies with capacities to regenerate themselves; they were not made for rent seeking economies that add no value to raw commodities and natural resources dug out of their earth. They were not made for an economy that has no input into the determination of the prices of the crude oil they produce.” (Onyekpere, 2012).

While this whole interesting and very important debate rages, we know where the pendulum will swing. We know the plan would eventually be approved by the National Assembly. But as we take that loan, there are a few issues we need to look into critically and possibly ask the right questions. The first is the Federation’s debt service to revenue ratio which the Debt Management Office (DMO) in its Debt Sustainability Analysis Report (2016) projects at 61.3 percent from 2016, up to 2036, breaching the country specific threshold of 28 percent. This implies that over half of our revenues as a Federation from 2016 to 2036 could be used to service debts. To underscore the enormity of the situation, and the need for urgent action, the DMO report highlights a very important message: “Therefore, there is an urgent need for the authorities to intensify all efforts aimed at diversifying the sources of revenue away from crude oil, as well as implement other intervention policies that will boost exports and capital-flows, such as foreign direct investments into the country.” Sanusi J.O. at the Seventh monetary policy forum organised by the CBN in 2003, stated that “The cost of servicing public debt (domestic and external) may expand beyond the capacity of the economy to cope, thereby impacting negatively on the ability to achieve the desired fiscal and monetary policy objectives. Furthermore, a rising debt burden may constrain the ability of government to undertake more productive investment programmes in infrastructure, education and public health.”

Can the Federal Government alone connect the dots? Do the states and local governments understand their roles in stimulating sustainable economic growth via diversification of the nation’s economy? (Probably issues for another day). If we are not able to translate the diversification rhetoric to economic growth and development for Nigerians, then we might be headed back to pre-2006 debt burdened Nigeria.

No doubt, the Federal Government has repeatedly stated its commitment to diversifying the economy and shoring up the nation’s revenue base, but how attainable are these commitments? For example, despite the government’s intentions to bring down food prices through initiatives that would ensure bountiful harvest, thereby significantly dampening the overall inflation momentum, the good people of Nigeria have just been warned of an impending famine in 2017. Can the Federal Government alone connect the dots? Do the states and local governments understand their roles in stimulating sustainable economic growth via diversification of the nation’s economy? (Probably issues for another day). If we are not able to translate the diversification rhetoric to economic growth and development for Nigerians, then we might be headed back to pre-2006 debt burdened Nigeria.

Another issue worthy of our attention as citizens of Nigeria is the utilisation of debts, whether foreign or domestic, over the years. According to the World Bank, since 1974, it has committed $1.2 billion for Agricultural Development Projects (ADPs) meant to increase farm production and welfare among small holder farmers in Nigeria. In a review of five of the ADPs and a supporting agricultural technical assistance project implemented between 1979 and 1990, carried out by the Independent Evaluation Group of the World Bank and assessed from their website on 11/10/2016, only two of the six projects had satisfactory outcomes. These ADP projects are: Ilorin ($27 million, 1979-1988), Oyo North ($28 million, 1980-1988), Bauchi ($132 million, 1981-1989), Kano ($142 million, 1981-1989), and Sokoto ($147 million, 1982-1990). The results from farming systems, extension methods, and input supplies, show that the increase in total agricultural production in each of the ADPs was below appraisal expectations. Performance of rain-fed crops was said to be especially disappointing, reflecting the difficulties with technology development and transfer programmes and input supplies. Overall, only the Bauchi and Kano ADPs were rated satisfactory. Yet these projects were executed with loans running over $500 million between the 70s and 80s.

Of particular interest is the Ayangba (Anyigba) Agricultural Development Project (AADP), not captured in the review above, but operational from 1977 to 1983. The Federal Military Government then obtained a 20 year loan of $35 million, with 4.5 year grace period for onward lending to the then Benue State Government for an agricultural project in the whole of the area now known as Kogi East Senatorial District. According to World Bank documents, the AADP covered an area spanning 13,150 km, representing some 1.5 percent of the total land area of Nigeria, centred around Ayangba, with a population of one million or about one percent of the total population of Nigeria, then estimated at 75 million. The project was meant to increase crop production through improved farm practices and extension services; livestock development through improved veterinary services and small stock; forestry development by establishing 1,000 ha of fuelwood and pole plantations; and fishery development through improved extension services and 15 fishing lagoons. Infrastructural development including 1,300 kilometres of feeder roads, 180 wells and project headquarters in Ayangba. Seed multiplication, applied research, evaluation and training were also meant to support project development, and input delivery through 30 Farmers Service Centres, credit facilities and market advisory services.

…we need to transit from ensuring that public goods and services are duly funded, to the point where the value of the budget as a tool of public sector management ultimately depends on how budget monies are used and managed. Budget performance should no longer be tied to the percentage of funds released. At the heart of the whole budgeting process should be efficient and effective implementation.

By 2003 when the loan was to have been completely repaid, assuming the country didn’t default, all that was left were but stories of the AADP; structures taken over and rehabilitated for use by Kogi State University in the 1999/2000 academic session; and of course, relics of agricultural machinery dotting the landscape. The project did not achieve its objective, yet the loan was repaid. Ibitoye (2012) in a five year projection into the income of contact farmers in that area and the whole of Kogi State shows that about 45 percent of them will fall below the N50,000 annual income level, while over 77 percent will fall below N100,000. This is disappointing, particularly for an area where a $35 million project was implemented. One would have expected the project to not only ensure sustainable development of agriculture in present day Kogi East but also serve as a catalyst for the development of the sector, the whole of Kogi, Benue and North Central Nigeria.

This loan must have been obtained close to over four decades ago, but it is the same story across sectors till date. It is therefore pertinent to stress the need for sustainability and effective exit strategies, as our country prepares for yet another circle of loan. The success of projects, particularly those funded with loans, should go beyond the implementation period and project lifecycles to having lives of their own and some catalytic effect beyond project areas. Much more importantly, however, we need to transit from ensuring that public goods and services are duly funded, to the point where the value of the budget as a tool of public sector management ultimately depends on how budget monies are used and managed. Budget performance should no longer be tied to the percentage of funds released. At the heart of the whole budgeting process should be efficient and effective implementation. It should be about results; about outcomes, and not about activities and outputs that seem to be the hallmark of our budgeting process. We should be concerned about the progress we are making towards solving the problems we had set out to resolve, and the changes created, by establishing clearly defined expected results, collecting information to assess progress toward them on a regular basis, and taking timely corrective action.

foraminifera

It is not an easy task, no doubt, especially with the paucity of data for monitoring and evaluation in this part of the world, but it is a move we must embrace urgently, otherwise we might not escape this debt trap ahead. The bulk of the responsibility, however, lies with the National Assembly. It must commence immediate efforts to put in place a Federal Accountability Act (FAA) that would, among other things, establish a Parliamentary Budgetary Office (PBO) with legislative mandate to provide independent analysis to the Senate and to the House of Representatives about the state of the nation’s finances, the estimates of the government, and trends in the national economy. As part of efforts to monitor fiscal sustainability, the PBO would develop a multi-year framework to analyse spending, performance and relative operational efficacy using public performance and spending data. The FAA would also ensure that all of government’s programmes are effective and efficient, focusing on results, value for taxpayers’ money, and aligned with current priorities and responsibilities.

The party has been long over. Let’s get to work.

Henry Anibe Agbonika is a development consultant. He can be reached on hagbonika@mainstayafrica.com

PremiumTimes

END

Be the first to comment