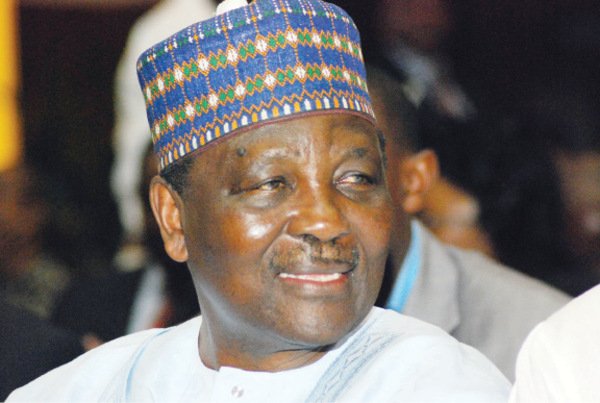

On Saturday October 19, General Yakubu Jack Gowon celebrated his 85th birthday. In the not so distant past, that event would have been marked with something akin to a public holiday. The Brigade of Guards would have organized an honour parade and speeches would have been made. Now power has moved on to new suitors but the truth is that Gowon remains a towering figure in contemporary Nigerian history.

He is perhaps the most influential figure of post-independence Nigeria. All the military officers who later played major roles in our history – Murtala Muhammed, Olusegun Obasanjo, Muhammadu Buhari, Ibrahim Babangida, Sani Abacha, Abdulsalami Abubakar and others, were all his officers. Gowon joined the West African Frontier Force, the precursor of the Nigerian Army, in 1954. Barely 12 years later, he was Nigerian military Head of State at 32. Unprepared for the job but he had to learn fast under difficult and unnerving circumstances. It was not the best of times but it was an era that was to define the place of Gowon in Nigerian history. He was to be in the saddle for nine eventful years, presiding over the bloodiest chapter in Nigerian history and still emerging from it, as Cambridge University once referred to him as “a man of Christian muscularity.”

About seven years ago when Gowon was about to celebrate his 78th birthday, I wrote him that I would like to collaborate with him in preparing his autobiography. My friend and old classmate, Niyi Obaremi, who was a big shot at the Industrial and General Insurance, IGI, helped to deliver the letter. Gowon was the chairman of IGI. Later I called the general and expressed my wish. He was very courteous and polite. He said however that he could not collaborate with me because he was already writing his autobiography. Seven years on, we are still waiting for perhaps the most important book on modern Nigerian history form a principal participant-observer.

No one knows the truth about contemporary Nigerian history more than Gowon. He was at the centre of it and for nine giddy years, he was the face of Nigeria. On the eve of the first coup in January 1966, Gowon had just returned from a course abroad and moved in to his official quarters at Ikeja army cantonment. The coup was to change everything. By January 15, 1966, Prime-Minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa was killed and the Commander of the Army, Major-General JTU Aguiyi-Ironsi, became our first military ruler. Ironsi appointed Gowon as the Chief of Army Staff (akin more to the military secretary) in succession to Colonel Kur Mohammed who was killed during the January 15 coup. The first Nigerian Chief of Army Staff, Colonel Adeyinka Adebayo, was also abroad during the coup.

It is still contentious whether Gowon knew about the coup that toppled Ironsi six months later. On July 29, 1966, a group of young officers from Lagos and Abeokuta barracks moved to join their co-conspirators in Ibadan where they kidnapped the Supreme Commander, General Ironsi, and the Governor of the West, Colonel Adekunle Fajuyi. The two men were eventually killed on the dusty road to Lalupon, a village near Ibadan. The assassins, though well-known, were never brought to book. They were the men who brought Gowon to power. They claimed their mission was to avenge the coup of January 15, 1966 during which many top military officers, mostly of Northern Nigerian origin, were killed.

For many weeks after he was proclaimed the Head of State, Gowon was commuting between his house in Ikeja Cantonment and his office, first at the Police Headquarters at Obalende and later at Doddan Barracks, the official residence of the former Minister of Defence. He was still a dashing bachelor who had his eyes on marriage. His love affair with Edith, a young beautiful Igbo lady, ran into trouble and eventually crashed. He eventually married the dashing Victoria during the Civil War in 1969. Politics and the affairs of state have become the dominant features of Gowon’s daily life. The dashing bachelor who use to drive about Lagos unknown and virtually unnoticed now goes to work with armoured tanks in his convoy. Power has located him.

The bloodletting in the military was not to end with Gowon’s ascension to power. In May 1966, there had been rumbling in the North which felt cheated in the new dispensation that propelled Ironsi to power. The riots of that May claimed thousands of lives. The anger of the North was not satiated even when power shifted with the assassination of Ironsi and more killings and mayhem took place in August and refugees in their hundreds of thousands, fled to the South, mostly to the Igbo heartland of the Eastern Region. Colonel Chukwu-Emeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu, son of a millionaire road-transporter, who had been appointed military governor of the Eastern Region by Ironsi, found himself on the frontline of the crisis. He rose to the occasion with dexterity.

Colonel Gowon took certain decisions that were to have serious repercussions on the future of Nigeria. First, he curiously decided to retain the corps of Lt. Colonels that were appointed as military governors by Ironsi. The only exception was Colonel Adebayo. After the kidnap of Ironsi and Fajuyi, a group of Yoruba leaders in Lagos insisted that another governor must be appointed immediately and suggested the name of Adebayo, then the most senior Yoruba officer after the hurried exit of Brigadier Babafemi Ogundipe and the January assassinations of Brigadier Samuel Adesujo Ademulegun and Colonel Ralph Shodeinde. Adebayo resumed in earnest in Ibadan.

Secondly Gowon agreed that soldiers should be moved to their region of origin. Without this decision, the attempted rebellion of the Eastern Region would have been difficult, if not impossible, to consummate. With the returning home of Igbo military officers taking over the barrack in Enugu, it made it easier to plot secession. Thirdly Gowon decided to release all political prisoners notably Chief Obafemi Awolowo, former Leader of the Opposition in the Federal Parliament and his followers in the old Action Group, AG, party and Isaac Adaka Boro, leader of the so-called Niger Delta revolutionaries who had taken up arms against the government of Prime-Minister Abubakar Tafawa-Balewa.

But the specter of rebellion in the East would not go away. Soon Gowon led his colleagues in the Supreme Military Council to Ghana to hold a peace talk in the resort of Aburi. Ojukwu came with secretaries and top civil servants. He had grown a beard, saying he was mourning the citizens of his region killed in what became known as the pogrom. Gowon and his team of military governors and other top commanders tried to be conciliatory. Ojukwu wanted everything. They gave him almost everything he wanted. To Ojukwu however, nothing was enough except the independence of the East or a semblance of it, which he called “voluntary confederation” guaranteeing the right to secede.

Later Ojukwu published his version of the Aburi Accord, apparently to prevent the release of the same report by the Federal Government. Event moved at a frenetic speed. Attempts to convey a Leaders of Thoughts conference in Lagos collapsed when Ojukwu ordered his delegation home. The final straw came at the Benin summit of the Supreme Military Council which Ojukwu again boycotted. It was that meeting that eventually decided to divide Nigeria into 12 states to forestall the pending possibilities of rebellion. Few days later on May 30, 1967, Ojukwu declared the former Eastern Region the independent state of Biafra. War was joined and it lasted until January 1970 when Ojukwu fled into exile.

Gowon was to stay in power until July 29 1975, when some of the middle-level commanders during the Nigerian Civil War agreed to topple him and installed one of their leaders, Brigadier Murtala Muhammed, as his successor. Ironically, it was the tempestuous Muhammed that led the group of officers and soldiers that brought Gowon to power in 1966. Gowon accepted his fate with what Ray Ekpu, the great editor, would have called “philosophical calmness.”

Despite his youth and inexperience, Gowon brought able and patriotic men into governance and poured Nigerian petrodollar into frenetic infrastructural development. He made us proud. Then he fell into temptation and idiosyncratic indulgences. How on earth did he arrived at the decision that “1975 is unrealistic,” after he had solemnly promised to hand over power to an elected regime on that date? It took Muhammed and Obasanjo four years to restore the honour of the military. Obasanjo handed over power to elected President Shehu Shagari on October 1, 1979. The Second Republic, born of hope, proved to be a brief interregnum.

Gowon went voluntarily into exile and became a student at Warwick University in the United Kingdom. A picture of him on the queue at the university cafeteria, prompted Muhammed to ask the Nigerian High Commission to intervene and offer Gowon all necessary courtesies befitting a former Head of State. Few days later, Muhammed was assassinated.

Since his return from exile during the Second Republic, Gowon has been threatening to publish his memoir and shed light on so many dark spots on our history. We need to hear the truth about our history from him. It is time for Gowon to let us know what he has written.

END

Be the first to comment