Last week, Aliyu Aziz, the Director-General of the National Identity Management Commission (NIMC), told journalists that the commission has enrolled 41 million Nigerians into the national identity data base.

While noting that Diaspora enrolment has been “greatly received by the Nigerians in other countries and it has been going well since the launch”, the NIMC-DG also disclosed that” enrolment is happening in over 15 countries across the world, with more countries to come on board in the near future.”

We commend the progress finally being made in terms of delivering a credible, harmonised database of the Nigerian population.

In the light of the previous efforts remarkable for corruption and unparalleled waste, securing 41 million enrollees – which represents about a quarter of the Nigerian population – might seem a big deal.

Yet, there is a sense in which the achievement might also be seen as modest considering that this is coming 13 years after the principal instrument – the NIMC Act – designed to give the work a new impetus, came into being.

Presently, the commission not only enjoys considerable support from foreign donors, including the World Bank, Agence Francaise de Development and the European Union, all of which have thrown in some $433m in cash, ancillary agencies such as the passport and immigration and the Federal Road Safety Commission have equally signalled their readiness to collaborate with the commission in its bid to get the job done.

Which is why we consider it a crying shame that the commission is still unable to muster the kind of urgency, let alone the energy required, to get going on a faster pace.

Of note is that the NIMC helmsman of course alluded to the problems: that of power, information technology infrastructure, inadequate enrolment centres and devices and insufficient sensitisation and awareness of the public, among others.

These are all too familiar problems. Aside being part of the job challenge in the Nigerian clime, we consider them as elements of the operating environment, which although challenging, are not necessarily insurmountable.

More than those however is what appears to be the commission’s overall lack of preparedness, hence its rather laid-back, non-business-like approach sadly in an age when Digital-ID has since become everything.

Had the NIMC management bothered to ask the telecommunication companies how they managed to undertake a similar exercise – capturing of the biometrics of their subscribers almost seamlessly even in far flung, remote corners of the federation, they might in fact find the missing link in the planning, resource mobilisation and the commitment to deliver on the task.

Obviously, the NIMC will need to urgently scale up the process by increasing the enrolment centres as a first step. Nigerians want to see the 4,000 enrolment points promised by the commission put into action as soon as possible.

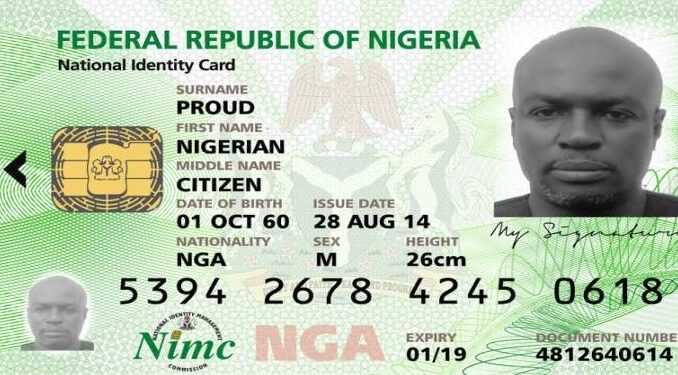

Secondly, making a song of the distinction between the National Identity Number (NIN) and the issuance of the e-card as the NIMC is wont to do, is disingenuous. Rather than rationalise the decoupling of the two, why not simply admit the constraints and then go for practical steps to address them? In any case, of what practical value is the NIN without the requisite card attesting to possession of same, more so in a country where most citizens neither possess the driver’s licence nor the international passport as a form of identity? If, as the NIMC says, the problem with the card aspect of the programme is one of funding, it should let the government know rather than seek escape in needless sophistry.

As it is, Nigeria cannot afford the luxury of another decade just to get citizens to have that basic ingredient in national planning. It’s high time NIMC stepped up to the plate.

TheNation

END

Be the first to comment