The last year of the four-year programme came and the civil war was still at it.

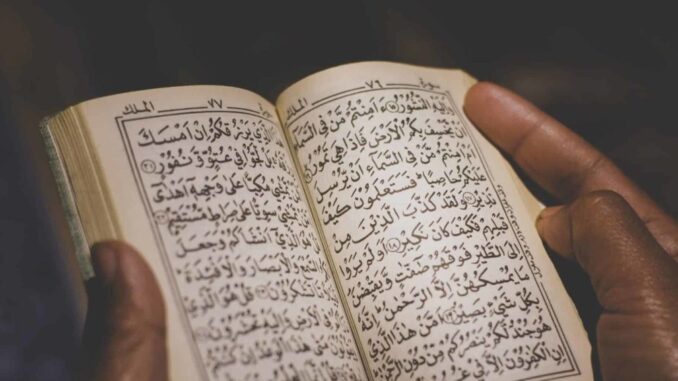

Usually, the fourth year should be spent in a country where the particular language of the programme is spoken. Egypt was our choice. But Classical Arabic is not spoken in Egypt, is not spoken in Saudi Arabia even, where the Qur’an was revealed to Prophet Muhammad. Our programme was a thorough grounding in Classical Arabic. This was to cause me a bit of embarrassment on my first visit to Egypt.

As I mentioned in my inaugural lecture at Stellenbosch, I grew up on the streets of Akure. No, I was not a street child. I had two homes, both belonging to my grandfathers and I moved from one to the other as the mood took me.

The streets of the town were a moving performance platform, raising dust in the dry season and splashing mud in the season of rains. The dances came in their time – Sibi for men, Omojao for ladies, Owaoropo for men – and devotedly I followed them, mouthing their songs with them, imitating their dancing steps after them. Then followed the egun-gun, not the rude and crude hastily dressed one who carried lashes, chasing the young along the straits and around the winding bends of the corners of the footpaths of the town. Rather, I followed the Egigun Ede, impeccably dressed in aged woven dark clothes of dark colours.

I took to acting at school. “I shall a drunkard be, Drunkard be, Drunkard be, I shall drink, And drink, And drink, And fall into the gutter, I shall a drunkard be!!!” And promptly I would fall drunk into the gutter.

I chose to write on Arabic theatre for my undergraduate long essay. While Classical Arabic had no theatre tradition, pre-Islamic poems had an incredible dramatic presentation that could be said to be nothing but drama and theatre. “Ladies and Gentlemen, this here we happen to be where the parents of my beloved used to camp. Here they forbade me to step into their abode.” The narrator would lament how he suffered for love and he and his companions would continue their ramblings in the desert.

As soon as I registered for my doctorate programme at Edinburgh University, I was lectured on my need to study and understand colloquial Arabic if theatre was my interest in Arabic language and literature. So, I booked a flight to Egypt. My Commonwealth scholarship included some travel grants. Edinburgh University introduced me to the American University in Cairo and that university found a professor to oversee my work while I was in Cairo.

I was staying at a cheap hotel along 26th July Street. At breakfast the first morning at the hotel, I naturally wanted to test my Arabic having forgotten the reason why I was in Egypt or Cairo in the first place. I called Ahmad over to my table and told him I wanted water. He looked at me. Me too I looked at him and repeated my order in perfect Classical Arabic “I want water.” It was a real game of looking me, I look you. He asked to know what nonsense I was talking about. A 10-year-old stood by the door, giggling and telling the steward I was reciting a verse of the Qur’an and I wasted my time telling the urchin I was not reciting any verse of any Qur’an.

More people had gathered around my table. Some were asking what it was I wanted. Was I reciting the Qur’an? Did I want someone to teach me how to recite the Qur’an? Then among themselves, they were saying I am a muezzin from Khartoum who is in Cairo to learn how to recite the Qur’an.

In the meantime, Ahmad the Steward had gone to call his manager to report a guest whom he did not understand. The manager waited impatiently while I explained to the school of Sudanese origin that I was from Nigeria on a Commonwealth Scholarship to study Arabic in Cairo and so on and so forth. “And you want water?”

Everybody laughed. I was not discouraged. “Na’am” I said “Yes”.

The laughter was louder and longer. And I had caught on. There was nothing wrong with my Arabic. Only people who are thirsty and want water do not ask for it that way.

“Inta aux maya?”

There was a general sigh of relief. That was all you wanted and you caused so much hullaballoo? Everybody said how they would have gone to their house to bring water if the hotel didn’t have drinkable water! Water was all I wanted.

Years later, it was my turn to laugh at these languages. It was in Geneva. I had been traveling in Angola with the refugee people. I had received a phone call where the caller asked me if I had one hour to spare because that’s how long the call might be. I said okay and we were now at the end of the project and I was in Geneva for final consultations. I had arrived early, as usual with me when I’m in a city with which I’m not familiar. Someone indicated the restaurant where we were going to hold to tête-à-tête. But first, we were to pick what we intended to eat and come and sit down. Again it did not take long to select what to eat and I walked back to the table for six reserved for us. As I placed my tray on the table someone said “no, no, no. I was not to sit there. Why? It is, he pointed at the notice, as if to say I was blind or I couldn’t read, reserved.” I continued to settle down hoping that in the meantime someone from our group would arrive and save me from the man who was waiting for me to go to another table. But nobody arrived. When I had settled down I turned to the man pestering me and told him, in the language of the notice, that the table was, in fact, reserved for me! At which point the pilot of our G550 arrived and said yes to the man.

END

Be the first to comment