It is the politics of power and domination being pursued by the North and Fulani herdsmen terrorism and not religion and corruption (or even agitation for self-determination of any indigenous ethnic entity in Nigeria), that would kill the country. All this means that we are dealing with a lust for power of a privileged minority, who use religion and ethnic difference to manipulate power and control over others.

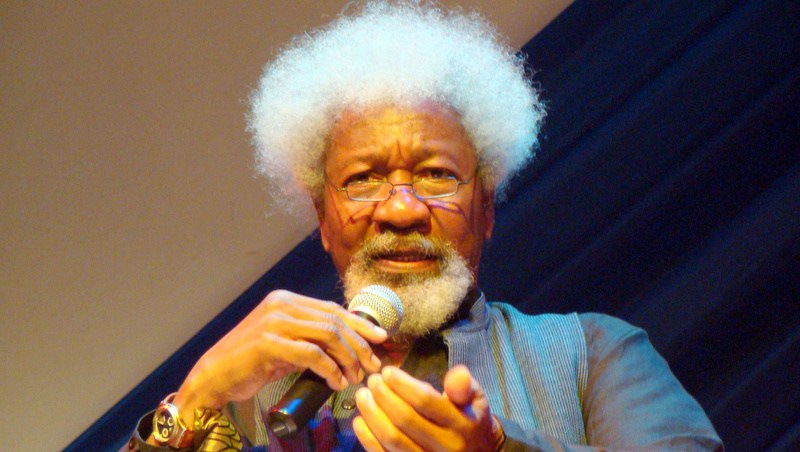

Our renowned Nobel laureate in Literature, one of Africa’s most respected intellectual giants, Prof. Wole Soyinka, was recently quoted as having accused religion as the cause of Nigeria’s woes and, indeed, of the world in general. Soyinka asked that religion be tamed and stigmatised. According to the Nigerian Punch newspaper of January 13, 2017, Prof. Soyinka at the presentation of a book, Religion and the Making of Nigeria, written by Prof. Olufemi Vaughan, said, among other things:

“President Muhammadu Buhari had said if Nigeria did not kill corruption, corruption would kill the country.”

Condemning killings in the Southern Kaduna in the name of religion, the Nobel laureate stated, inter alia:

“I would like to transfer that cry from moral zone to the terrain of religion. If we do not tame religion in this nation, religion would kill us.”

“I do not say kill religion, though, I wouldn’t mind a bit if that mission could be undertaken surgically …” (Wole Soyinka, Abuja, January 13, 2017).

One must admit that this is not the first time our learned and renowned Nobel laureate, Prof. Soyinka has made such a round-table condemnation and accusation of religion as the problem of our nation and the world in general. In one of his international Television interviews a few years ago, Soyinka made similar allegation as follows:

“Organised religion in my view is more a curse than a blessing. I believe that religion should be very personal.”

Referring to the Nigerian context in particular during the said interview, Soyinka added:

foraminifera

“Nigeria does not want to confront its history. Nigeria is living in denial … as long as it refuses to confront the wrong it has done to the Igbos”.

I purposely decided to add this last quotation because, I think, that is where he demonstrated the courage to call a spade by its name and hit the nail on the head. However, for his stigmatisation of religion as a curse other than blessing, and as the cause of our nation’s woes, I beg to differ. I have never disagreed or criticised our revered literary giant and I do not intend to do so in the present article at all. Because, no matter what, the person of Soyinka is one good news, we as Nigerians and Africans in general will continue to be proud of. Soyinka’s literary achievement and stance in some critical moments of our turbulent history as a nation and continent is something every relatively conscious individual should always appreciate and applaud. However, I disagree with Soyinka on this particular issue of his stigmatisation of religion as a curse other than a blessing. As an intellectual, however, I guess, he raised that issue in order to awaken our consciences and intellectual curiosity to a deeper problem of our Nigerian nation-state. So, my article is only a contribution to that debate which I think, is what Soyinka himself is calling for when he made the accusation against religion. Our intention, therefore, in this article is not to pick quarrels with our Nobel laureate but rather to respond to his call for debate on the leadership crisis and social problems confronting our fragile nation-state, Nigeria.

For me, Nigeria’s problem is NOT religion! Neither is it corruption. Rather it is the unwillingness of its political leaders and elites like Wole Soyinka and us all to confront our history as a nation-state. I stated this fact vividly in my last two articles published during the last Christmas and 2017 New Year festivities. One could have expected Prof. Soyinka to use that occasion of the book launch on Religion and the Making of Nigeria to address the problem of the failure of leadership as the main reason for Nigeria’s woes as a nation-state. Soyinka would have told the Nigerian political class and leadership that corruption is not really our problem, because there is something much deeper, which is fueling both corruption and religious violence in Nigeria. Rather than launch an unnecessary attack on innocent religion, Soyinka could have made use of that occasion of the book launch, to rise to the hallmark of personal example, and tell the centres of power in our nation that they themselves are the problem of the nation and not religion or corruption. Human beings’ manipulation of divisive elements in culture and religion for selfish political gains and power is the demon we are to fight and kill, not religion per se.

In other words, Soyinka’s unmitigated attack of religion does not get to the heart of the Nigerian story, our founding story as a nation-state. Moreover, his attack does not pay sufficient attention to the possibility that politics in Nigeria in particular, and in many other African nation-states in general, have not been a failure, but have worked very well. Chaos, war, violence, the killing of innocent people in the name of ethno-religious bigotry, and the tragedy of corruption in our political landscape are not indications of failed institutions or the nation-state itself, they are ingrained in the very imagination of how nation-state politics works. In other words, even though we condemn religion as a cultural element that could easily be manipulated by religious bigots and political jobbers for selfish-interest to cause violence and disorder in the society, it is not the whole story. Soyinka, in his stigmatisation of religion, paid very little attention to the story of the political institutions of Nigeria as a nation-state: ‘how they work and why they work the way they do.’ It is at this narrative level that a fresh conversation about the place of religion and its social engagement in the Nigerian nation-state politics must take place. This is a new conversation, which we need to confront to address the enduring issue of relationship between politics and religion in the making of Nigeria as a nation-state.

In the first place, what is religion? According to Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary:

“Religion is belief in the existence of God, who created the universe and gave human beings a spiritual nature which continues to exist after death of the body.”

The dictionary goes further to say:

“It (religion) is a particular system of faith and worship based on such belief: the Christian, Buddhist and Hindu religions or practice of one’s religion.”

Therefore, religion is about God and our worship of Him as our Creator and source of life, both here and hereafter. Religion is ingrained in the fabric of human nature and therefore, divine. In other words, for Soyinka to say that we should tame religion is like asking that we tame the existence of God in our lives and our worship of Him as our Creator and Source of life, both here and hereafter. This is impossible. As John Mbiti once remarked, Africans are notoriously religious. Religion pervades the entire existence of the African. This is true not only of Africans but also of all human beings and the created reality. We cannot live or even be without religion. Religion is the soul of our being and existence. Religion is also the spiritual ferment of the world. Without it, we are nothing and the world has no meaning in itself without religion. It is only for intellectual jingoism and debate that one could say he or she is not a religious being or does not believe in the existence of God and the life-after. Therefore, Soyinka’s call that religion be tamed raises some fundamental questions than the problem it pretends to respond to. Again, we can ask, “Is it religion or the human person that needs to be tamed?”

True enough, there are causes of violence impeded in some religious beliefs and elements. This does not mean, however, that there is a direct link between religion and violence. Because to hold the view linking religion with violence is to obscure the authentic thought about people’s belief in the One True God, who is the Creator and Father of us all. The purity of religious faith in the One True God must, therefore, be always recognised as the principle and source of Love between human beings. This observation is important because it helps to correct the wrong impression created in some modern scholarship since the rise of violence and religious fundamentalism in recent times, about relating monotheistic religions like Christianity to violence. It is absolutely wrong to say that there is a direct link between religion and violence.

Again, this last point is important because it helps to evaluate, critically, a major misconception in dealing with the contemporary debate on religion and violence, which some scholars would want to avoid. It is the refusal, particularly in the mainstream scholarship and among secular elites, to see the link between the rise in religious fundamentalism and violence with the current geopolitical and economic systems that have impoverished many countries of the southern hemisphere, where religion is still taken very seriously and distinction is hardly made between it and other aspects of life. Some contemporary scholars mistakenly blame religion, as a matter of fact, as responsible for most of the contemporary violence and conflicts. These are scholars who see the present situation of religious violence as a clash of civilisations, one secular and the other primitive, with violent religious systems. But this view is another attempt to reinforce the cultural superiority and purity of one group on the other, which were discussed in my previous articles.

Some modern scholars may also like to argue that religious faith is waning. Thus, diplomats and academics “want to separate religion from economics or politics and blame everything on poverty or politics but would argue that violence is part of religion and economics and politics draws them out.” This view claims that it is religious history, religious sensibilities, and religious passions which drive religious conflict and turn other disagreements into violent confrontations. Again, this type of reductionism misses the key issues in the conflict and can lead to major international misunderstandings and catastrophes, of which the September 11 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center in New York City is the most egregious example.

Therefore, it is incorrect to blame everything on religion, as far as the present social conflicts and violence are concerned. We need to take religious claims, histories, and passions seriously but without making judgments about the legitimacy or ultimate morality of any particular religious position in fostering violence. In this regard, we have to acknowledge that many works on religious conflict and violence are avowedly partisan and judgmental, sometimes in fervent defense and in others in militant opposition. Our position in the present article, however, is that we take a more balanced academic view, in which we seek to better understand the unique confluence of history, culture, manipulation of religion, politics, and group psychology that gives rise to violence, and avoid any stigmatisation or stereotyping judgment on any particular religion or group of people. The goal of viewing religion and violence from this perspective is to present reasoned interpretations that will make sense of the present global religious conflict and that will provide much-needed information for informed and reflective decision-making in social reconciliation and conflict management.

The Historical Dimensions

Historians and political scientists have shown that most of Africa’s problems today are rooted in the continent’s colonial past. It is today compounded all the more by the unwillingness or, rather, incapability of African ruling elites and intellectuals to rise up to the challenges of personal example, to right the wrongs of the past, and save the present and future generations of Africans from sinking further into the abyss of despair and hopelessness. This is the problem of Nigeria, as with other African nation-states created out of the arbitrary colonial partition of the continent in the spirit of the European Berlin Conference of 1885. Until we address the historical injustice on which our Nigerian nation-state and indeed the modern African nation-states in general, is founded, we will continue pursing shadows and living in denial. Therefore, our problem is our ‘history’ as a nation-state and NOT religion!

One should not forget that the few African intellectuals and political leaders who had attempted in the past to address this historical wrong of the arbitrary colonial partitioning of the continent were either disgraced out of office or denied international recognition of their literary achievement, as the case may be. It is no longer secret that this is the major reason Prof. Chinua Achebe, the father of African literature, was denied the Nobel Prize Laureate in Literature, in spite of his unparalleled achievement in that academic field in recent world history. Achebe’s uncompromising stance in his writings, especially the novels, in revisiting and denouncing colonial dispossession of African culture and traditional societal organisation, is unpalatable news for the world powers and their local spinoffs, as well as stooges they had planted in the continent.

Again, on the political front, great and pro-African leaders like Patrice Lumumba of Congo, Thomas Sankara of Burkina Faso, and a few others, were brutally murdered and disgraced out of office. Their offence was that they dared and wanted to negotiate the arbitrary colonial arrangement that gave birth to the fragile nation-states they found themselves in after the so-called political independence of the 1960s. Moreover, in recent times, African leaders like Charles Taylor of Liberia, Laurent Gbagbo of Ivory Coast, among others, were disgraced out of office and charged to the International Criminal Court in The Hague in The Netherlands, on an exaggerated accusation that they committed crimes against humanity by killing their own people. Even though, there may be some elements of truth here, however, this is not the whole story. It is not also the main reason why they were arraigned in the first place before the International Criminal Court in The Netherlands. No.

The fact is that every discerning mind knows that any African leader today with a pro-African agenda, who could dare to request to negotiate the colonial arrangement and management of African natural and mineral resources in his or her country, hardly lives to see the next day in office. The brutal murder of Gaddafi of Libya by the combined Euro-American NATO forces, and the concomitant civil war in the country since then is a classical example of what awaits any African leader that dares the modern imperial nations’ interests in the continent. This is why most of present-day African political leaders and Heads of States chose to behave like yuppies and sell-outs to avoid being disgraced out of office. None of them has the courage to hold the bull by the horn and lead their people across the Red Sea – out of servitude in their own land. This is why Zimbabwe is suffering today. In spite of all the shortcomings of the maximum leader and old-man there, Mugabe’s sin, no doubt, is that he wanted to secure African land for his people after over 200 years of deprivation and subjugation under Apartheid regime. He felt that after about twenty years of their so-called political independence, the Apartheid structure and colonial arrangement that left the control of the arable and fertile land of Zimbabwe at the hands of the White minority, has to go. The indigenous and ethnic Africans of Zimbabwe have been living in a constricted non-fertile land. Mugabe felt that this unjust arrangement must be renegotiated and corrected too. Mugabe’s attempt to right the wrongs of the past, and the refusal of the modern centres of power to that African request, is the major reason for the economic isolation of Zimbabwe today and therefore, the suffering of the people of Zimbabwe. Period! No attempt to demonise Mugabe will ever succeed to remove this historical fact and injustice Zimbabwe, had been subjected for years now.

This means that the African leader’s pro-African stance to dare and question the past mistakes against his or her country is at the root of modern African problem, and NOT religion. The African leader who chooses not to address the historical mistakes in his country and correct it in the light of the present suffering of his people, has never received any rebuke from any of the centres of power that still regard themselves as friends of Africa. Even when such an African leader or Head of State is committing various kinds of crime against humanity in his domain (for example, as it is presently being experienced in Cameroun and Nigeria, among others), nobody cares. The world’s centres of power look the other way. The International Criminal Court at The Hague is not for such a ‘good boy’ African despot, even if he may be killing his own people extra-judicially on a daily basis. The important thing is that the African despot protects the foreign interest and so saves his own parochial local political domination and interest. The Court at The Hague in The Netherlands was not created to promote African interest. Rather, it is there to handle any pro-African leader who may dare to question colonial arrangement in any of the modern African nation-states. The denial of this fact is part of our problem as a people today in Africa.

Added to the above point, is the fact that the modern world is NOT governed by religious principles or even sentiments. The world as we live it today is controlled by the politics of race and economic supremacy. The military supremacy and arrangement of the modern centres of power – including the so-called international organisations and multinationals, are created to serve and protect these fundamental interests of the modern imperial nations. Therefore, the enemy is not religion, if we can use that term. The real enemy and problem of the modern world and by extension, our nation, is racial politics and economic dominations as well as ambitions of the presumed superior races and world modern centers of power.

In the African context, for example, it is no longer secret that the world’s centres of power, which often pretend to be our friends, have never supported indigenous peoples for self-determination! Yes. Of course, self-determination as a human right for indigenous peoples was recently recognised in the United Nations Conventions, and even African Charter. However, that is where it ends! Recent history tells us that the world’s centres of power have always worked against the emergence of indigenous people as nation-states in its own right. Without delving into details, and leaving aside the tragic experiences of the natives and indigenous peoples of the Americas and the Pacific, of what is today known as Australia and New Zealand, at the hands of foreign settlers and colonisers, it suffices to mention a few examples of the African experience. The Berlin Conference of 1885, in which Africa was arbitrarily partitioned by the colonial powers without any reference to ethnic and indigenous Africans themselves, was a joint venture of the West and the Arab power, which was represented at the conference by Turkey. It was the second stage in the suppression and subjugation of indigenous and ethnic Africans by the two self-proclaimed colonial superior races that invaded the continent in our checked history. The first in recent times, however, was the Trans-Saharan Slave Trade carried out by the Arab merchants. After the early centuries rampage of the Arabs in Northern Africa, which had changed the demographic and racial contour of that part of Africa forever, the original inhabitants of Egypt and the Maghreb Africa who were really Black ethnic and indigenous Africans were forced further back into the southern regions of sub-Saharan Africa. The merchants of the Arab Trans-Saharan Slave Trade and European Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade that came later through the Atlantic Ocean, all invaded sub-Saharan Africa, enslaving and exporting the human resources of Africa as slaves in the foreign lands for economic enrichment. That was the beginning of the denial of the human dignity of the African person. The dispossession of our humanity by fellow human beings. This is what Engelbert Mveng, an African theologian from Cameroun calls anthropological poverty, the indigence being – “which has banished Africans from the world history and the world map. It is impoverishment of Africans through Slave Trade and colonialism, which is structural, comprehensive, total, and absolute, on the continent, in the states, in cities as in the countryside.” For Mveng, the anthropological and structural poverty have neither moral value, nor spiritual value, nor any other kind. They are simply evils that must be torn out by the roots.

The Salve Trade and colonialism, championed by the Arab and the West in Africa, was a racial trade and subjugation of indigenous ethnic Africans. Simply! The Europeans never enslaved the Arab Africans, whether Muslim or Christian, and so did the Arab slave merchants themselves. Only the Black, ethnic and indigenous Africans were subjected to slavery by the Arab and Western slave merchants. Only the Black ethnic indigenous Africans were treated as commercial commodities for the economic enrichment of the self-acclaimed superior races. The Arab Africans in Egypt and the Maghreb, as well as the Fulani Arabs that later settled in the Upper Guinea of West Africa and Sudan, were never subjected to the slave trade as the ethnic indigenous Africans.

Furthermore, during the colonial era of the 19th century, when Slave Trade was abolished, and Africa came to be partitioned by the two colonial centres of the Arab and the West, the new African nation-states, like Nigeria, were created by the colonial masters to favour themselves and their Arab friends, Fulani settlers who migrated from the Upper Guinea. This means that the new African nation-states were partitioned in such way as to favour the Arab settlers, such as the Fulani in West Africa and patches of other Arab settlers in other parts of sub-Saharan Africa, as well as in the North of the continent, which is already controlled by the Arab chiefdoms and caliphates. This is how Nigeria came to be created as a nation-state and handed over to the Sokoto Caliphate by the British colonial overlords. This is the root of Nigeria’s problem.

Have we as a nation ever wondered why the intellectual giants and our pan-African frontline politicians, such as Nnamdi Azikiwe, Obafemi Awolowo, and other freedom fighters in the struggle for independence, were not given political power at independence in 1960? The government of Nigeria came to be handed over to individuals and a geographical zone that did not participate in the struggle for independence. Those who refused to be part of the ideals of African liberation, who never believed in Africa and in the human dignity of Africans, were handed over power after the political independence of an African nation-state? This is the bane of our problem. Not religion.

Our elites, intellectuals and political leaders are yet to have the courage, and capability, to address our country’s problem as a nation-state in a creative way for truth, peace and justice to reign in our land. It was for this kind of naïve approach and attitude to our perennial and unresolved historical problems that we had the 1966 military coup, and the counter coup the year after in 1967. The first pogrom against the Igbo and other Easterners living in Northern Nigeria in 1954 was in furtherance of this unresolved historical problem. The second Northern Nigeria pogrom of 1966 – the mother of all pogroms against the Igbo and other Easterners living in the North – owed its root cause to this unresolved historical problem of Nigeria as a nation-state. The Nigeria-Biafra War that claimed over three million innocent lives, especially, of the Easterners (mainly through starvation and blockade), has remained the most tragic expression of this unresolved Nigerian problem. Almost after about fifty years since that war between Nigeria and Biafra was fought, we have not been able to come to terms with our history and reality and to address it creatively for the sake of our children, the future generation. We have continued to pretend as if nothing has happened or as if the war has really ended.

By the way, have we forgotten that Egypt represented the Arab world in the execution of the Nigerian Civil War of 1967 to 1970. Britain and Russia (two Cold War arch enemies) all united as friends and invited their Arab friends in the execution of the Civil War in favour of the federal government then in Lagos against the indigenous Africans of Eastern Nigeria. I still remembered vividly from where I was hiding as an eight year old boy during the civil war in Eastern Nigeria, seeing the face of the Egyptian pilot in a war jet-plane made in Great Britain, when his plane descended so low and dropped a very heavy bomb in our village square very close to our house in 1969. On other occasions, I had also seen the face of a Russian war pilot hovering over our village with his jet plane. This is to show that the Civil War was more than the slogan: “To keep Nigeria One is a Task that must be kept.” There is also the racial undertone to the Nigeria-Biafra War. The self-acclaimed superior races united among themselves during the Nigerian Civil War and vowed that indigenous Africans of Eastern Nigeria must never be allowed to attain self-determination. The colonial boundary of Nigeria they vowed must be respected at all cost. In this way, the subjugation of ethnic indigenous Africans of that country is a permanent project.

In other words, instead of accusing religion as the source of our problem, why can’t we talk of unraveling those elements of our history that still haunt us as never before. Why can’t we also unravel those elements in cultures and religion that are often manipulated to induce people to commit acts of violence and conflicts in the society? The Nigerian context, which Soyinka seems to be addressing, points to a deeper problem. For instance, if religion is really the problem, we could not have gotten the June 12 election annulment. Abiola, could have been declared the winner of that election which was judged the most free and fair in the history of Nigeria. In spite of the Muslim-Muslim ticket, Abiola’s election was annulled. I remember A. Nzeribe, the Maverick politician and senator from Oguta in Imo State, asking Abiola during the electioneering campaign, what had he (Abiola) for his people. Abiola was quoted as having replied that ‘he does not need the Igbos to rule Nigeria.’ So, his choice of a Muslim-Muslim ticket to appease the Northern oligarchy and the Muslim population from there. Abiola himself was a devout and an avowed Muslim. He made a lot of contribution for the promotion and spread of Islam in Nigeria. I remembered how Abiola’s then Newspaper, Concord was used as an arrowhead in attacking Christianity in Nigeria, in particular, the Catholic Church at the time. The newspaper’s attack on the Catholic Church, especially the person of the Pope, was very disgusting that the retired Catholic Archbishop of Benin City, Most Rev. Anthony Ekpo had to ask Nigerian Catholics to stop patronising Concord. In spite of all these, Abiola’s rooting for his Islamic faith in Nigeria against Christianity and Igbo people, however, at the most critical moment of his quest for power, his Muslim brothers from the North at the helms of nation’s affairs, annulled the presidential election in which he was the clear winner. So, where is the religion here? The fact is that Abiola was a Muslim, quite right, but fundamentally, he was an indigenous ethnic African, and therefore not from the ‘superior race’ of the Arab Fulani Muslims or oligarchy in the North that controls Nigeria.

Even the last election, which brought Buhari to power, shares the same index as that of Abiola. Senator Tinubu, the national leader of APC and the man thatwho was the brain behind the Western Nigeria rooting for Buhari to win the last presidential election against Goodluck Jonathan, an Ijaw, a minority ethnic group in South Eastern Nigeria, was sidelined immediately after the inauguration of the Buhari regime. Tinubu is a devout and avowed Muslim but he forgot history. He forgot as King Yunfa, the Hausa Sarkin of Gobir (now called Sokoto) did when he hosted a Fulani immigrant called Dan Fodiyo and his group in February 1804. As a result of this and since 1808, the whole Northern region lost its kingdom and were replaced by the Fulani emirates. King Yunfa is said to have been killed in 1808 and the Fulani warrior (Usman Dan Fodiyo) established the Sokoto Caliphate, making himself Sultan. In a similar way, the Afonja Yoruba dynasty of Ilorin compromised by allowing a Fulani warrior known as Janta Alimi to settle in Ilorin. The Fulani guerrillas later killed Afonja in 1824. And Ilorin, a Yoruba town under the Oyo Empire, fell into Fulani hands, becoming an emirate under Sokoto Caliphate till today.

Furthermore, the choice of the Northern states in Nigeria to superimpose Sharia legal system over and above the Nigerian Constitution in their region is another manifestation of the permanent symptomatic problem of Nigeria as a nation-state. It has a political undertone more than the religious sentiment it often invokes. What is at stake in that action of Northern Nigerian states is nothing but disregard of indigenous ethnic Africans from that zone and the presence of other Nigerians from the South living with them! The enthronement of Sharia legal system over and above Nigeria’s Constitution by a section of a country, which pretends to be running a secular state, is a camouflage of a deeper problem Nigeria as a nation-state is yet to address. The continued massacre of other Nigerians resident in the North at any least provocation, the creation of terrorist groups like the Boko Haram and Fulani herdsmen foot-soldiers by the Northern elites and political ruling-class, has a political undertone other than religious. The fact that none of these terrorists (whether Boko Haram or Fulani Herdsmen militant) has been arrested and brought to justice shows that they are working for their pay-masters, who may be those controlling the government machinery of the country. But it also points to the fact that for those in power, the lives of those terrorists from the North is valued more than the lives of other Nigerians who are judged to be from the inferior race.

The same is with the marginalisation of other ethnic groups, especially, the Igbo, in the present federal government political appointments and denying them of infrastructural allocation. Any group that is viewed as antithetical to the ideals of the superior race is immediately sidelined. Does it surprise anybody that our elites and the so-called international community seemed to have awakened from their slumber to the on-going state sponsored violence and disturbance in Nigeria simply because, it has just happened in the ‘North.’ Last year alone, for example, many villages were reported to have been wiped out by the Fulani herdsmen militia in the Idoma zone of Agatu in Benue State, still within the North central region. But perhaps, because the Idoma people are close neighbours to the Easterners, the so-called international community and our revered elites and intellectuals left them to their fate. The same last year when many villages in Uzo-Uwani local government area of Enugu State in Eastern Nigeria were burnt down and many lives lost caused by the same Fulani Herdsmen militia invasion of the area. How many people raised alarm then from other parts of the country about the killings of innocent people in Uzo-Uwani, Enugu State? Where were all these prophets and intellectuals now pontificating about the killings in Northern Nigeria? The military and other security agents have been implicated several times in the continued extra-judicial killings of unarmed Igbo youth in Eastern Nigeria who are carrying peaceful protests for self-determination of their people. During last Christmas and New Year celebrations, the whole Igboland in Eastern Nigeria was militarised. Where were these are intellectuals and prophets who are talking? None of these our intellectuals and self-appointed prophets has openly come up to condemn either religion or politics or anybody at all for the carnage the military and police are doing in Eastern Nigeria since the present regime came to power in 2015. Now everybody is pontificating because something of that kind is increasingly mounting in the North. Who is fooling who? I am yet to fathom whether by our action so far, are we not saying that Britain did not make any mistake in handing over Nigeria to the North at our political independence? I am confused here!

There are other examples, more disturbing than the ones recounted above. But these are sufficient to tell us that religion is not really the issue. Mind it, evil must be condemned whole sale, wherever it raises its ugly head. So, we are not saying that what is happening in the North, the killing of innocent citizens there should not be denounced by all and sundry, and justice be done. No. Our point is that our approach to such a national problem as nation-state should be a common concern. We should stop practicing selective response to what in real sense should be a common concern and problem. Till now, our approach to such issues that should in normal circumstances arouse our collective condemnation and response, has remained selective and ethnic bias. This is the Nigerian problem! It is the ethnic bias that has continued to underpin the emergence of Nigeria as a liberated, free, peaceful and united nation-state.

The Nigerian Story as a Nation-State

We have been behaving as if ours is a homogenous nation-state and as if indeed many African nation-states today, actually, fit into the traditional definition of states by social scientists. We pretend still as if the consents of different ethnic nationalities logged together in that geographical expression called Nigeria mattered at all in its creation as nation-state by the foreign colonial powers in 1914. No. Nigeria is a heterogeneous nation-state and so must address its problem from the perspective of its history as a multi-ethnic nation-state. Traditionally, political scientists have employed two terms to identify the structure of the political entity known as the state: Homogeneous and heterogeneous. The homogeneous state – the nation per se, is defined as ‘a single people, traditionally living on a well-defined territory, speaking the same language, practicing the same religion, possessing a distinctive culture and united by many generations of shared historical experience.’ Japan and the two Koreas are good example of homogeneous states. A heterogeneous or multiethnic state or nation comes about after the gradual fusion that may occur between the diverse national and cultural groups within the state after a prolonged maintenance of political control by the central government over a given territory and its inhabitants. United Kingdom (or Great Britain) is a classical example of a heterogeneous state, though the call for devolution and continued struggle of the minorities within the kingdom shows that all is not yet well with such a fusion.

Today, political scientists argue that most African states lack at least three elements necessary for nationhood: a national language, a predominant religion and a long history of organised cohabitation among its various peoples. Thus, many political scientists are beginning to suggest that the African problem will only end with a permanent separation of the ethnic groups involved. They argue that the real situation is not as a result of corruption or religion, but a struggle for second independence of the indigenous Africans from the domineering ethnic-group. Thus, the advocates of this view believe that the issue of nationhood in Africa must be resolved before genuine democracy and community development as well as real relationships among neighbours can take root in the continent.

All this implies that understanding the stories and imagination that lie beneath the founding of Nigeria as a nation-state and the ability to interpret them in light of our present struggle as a people and nation, may aid all of us to rise to the demands of nation-building and leadership of inclusion founded on truth, justice, freedom and honesty.

Stories not only shape how we view reality but also how we respond to life and indeed the very sort of persons we become. In other words, we are how we imagine ourselves and how others imagine us. But this imagining does not take as an abstraction in the world of fantasy or as the unbounded free play of a mental faculty called the imagination. The idea that we can be anything we wish to be is one of the most insidious lies we can ever entertain. Who we are, and who we are capable of becoming, depends very much on the stories we tell, the stories we listen to, and the stories we live. Stories not only shape our values, aims, and goals; they define the range of what is desirable and what is possible. In other words, stories are not simply fictional narratives meant for our entertainment; stories are part of our social ecology. They are embedded in us and form the very heart of our cultural, economic, religious, and political worlds. This applies not only to individuals, but to institutions and even nation-states like Nigeria. As the Ugandan African theologian, Emmanuel Katongole puts it: “That is why a notion like “Africa” names, not so much a place, but a story – or set of stories about how people of the continent called Africa are located in the narrative that constitutes the modern world.”

Ngugi wa Thiong’o, in one of his lectures, points out that image resides in the memory and that the story we tell about ourselves, as it were, is a process of helping the African people to draw their own image unfettered. Images are very important. This is the reason why many people like looking at themselves in the mirror and like to take photos of themselves. In many African societies, the shadow is thought to carry the soul of a person. But in our context, we are talking of the image of Nigeria as a cultural, religious, philosophical, and even as a physical, economic, political, moral and intellectual universe. In the conversation with Nigeria as a nation-state, there is a tendency to show that this image resides in the memory. So also are dreams and hopes, as well as the Nigerians’ concept of life and struggle for survival. The question is how are we as a people remembered in our own consciousness and in the consciousness of the outside world?

This implies that even though the stories we breathe and live may, on the surface, appear invisible, yet it does not mean that their hold on us is less powerful. On the contrary, to the extent that the stories which form our imagination remain invisible, they hold us more deeply in their grip. This is what makes the story of the institution of a nation-state like Nigeria even more powerful than has been acknowledged. Chancellor Williams, an African American scholar, in his seminal book, The Destruction of Black Civilisation, cites a passage from a Sumer Legend (an ancient Black People) that may best explain the point we have been trying to stress here:

“What became of the Black People of Sumer?” – The traveler asked the old man, “for ancient records show that the people of Sumer were Black. What happened to them? ‘Ah’, the old man sighed, they lost their history, so they died.” – “A Sumer Legend.” (Cf. C. Williams, The Destruction of Black Civilisation, Third World Press, Chicago 1987, p. 15).

Here a question easily suggests itself: “how many of Nigerian young generations today are conversant with the founding story of Nigeria as a nation-state – the founding stories of the nation’s institutions and social systems? How many Nigerians of today have a clear knowledge of the history of the evolution of Nigeria as a nation-state, and the role played by our past heroes in the birth of Nigerian nation-state? The present reality of Nigeria challenges us to dig deep into our past as a nation-state in order to rejuvenate it based on those values and ideals which our founding fathers and past heroes have labored and died for.

According to Bievenu Mayemba, a Congolese Jesuit Priest, a story tells us about the past, supports us in the present, and prepares us for the future: “It involves the memory of the past and the memory of the future… It also involves a promise and tells us we should not move forward without looking back.” Since our African memory is future-oriented despite John Mbiti’s phenomenological interpretation of the African concept of time, we look back to the past, to the myth of our ancestors, for the sake of the future and future generations. This is an essential task, especially in the Nigerian context, that is a classical example of colonial dispossession of Africa’s cultural heritage. Chinua Achebe in his magnus opus novel, Things Fall Apart, which has its setting in Nigeria (Igboland), captures very well this colonial dispossession of our heritage as the founding story of the crisis we are living today in Nigeria and in indeed in the whole of Africa:

“He has won our brother and our clan can no longer act like one. He has put a knife on the things that held us together, and we have fallen apart”.

The Nigerian Jesuit Priest and theologian, A.E. Orobator from Benin City, recently, made a very significant theological re-appropriation of Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (cf. A.E. Orobator, Theology Brewed in an African Pot, Orbis Books, Maryknoll, New York 2008). In fact, Achebe’s Things Fall Apart could serve as a starting point for diagnosing the maladies of the present-day Nigeria from the point of view of the power of the founding story and memory of Nigerian people and nation-state. Achebe’s novel, though published many years ago is yet to be read and taught to Nigerian children with a prophetic vision. Things Fall Apart is Achebe’s contribution towards the socio-political and cultural regeneration of Nigeria and indeed the African continent. Could the present generation of Nigerians take up Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart and make it relevant to the emerging Nigerian society?

Conclusion

The Nigerian problem is deeper than the accusation of religion. Cornelius Tacitus made the following timeless remarks: “The lust for power, for dominating others, inflames the heart more than any other passion.” It is the politics of power and domination being pursued by the North and Fulani herdsmen terrorism and not religion and corruption (or even agitation for self-determination of any indigenous ethnic entity in Nigeria), that would kill the country. All this means that we are dealing with a lust for power of a privileged minority, who use religion and ethnic difference to manipulate power and control over others. Emeka Ojukwu left us this legacy of his words of wisdom:

“The person marginalising me is the person who thinks he has something to gain by maintaining the war situation without the fighting. They don’t allow you to fight but they want to keep the war situation alive”.

In other words, part of our problem as a nation is the continued inability of our elites and intellectuals to point out these things and speak directly to those responsible for a change of mentality and approach in their pursuit of power and leadership style. This is actually, what prompted me to write this article and share with Soyinka how his book, The Man Died, inspired me as a young Nigerian secondary school student in the 1970s. Soyinka’s phrase that inspired me most is as follows:

“The man died in him who remained silent in the face of tyranny.”

In another context, Soyinka says, “The greatest threat to freedom is absence of criticism.” In reading these marbled words of Soyinka and hearing him today, hide under attack on religion to address the social maladies of Nigeria as a nation-state, I felt confused! I am yet to reconcile Soyinka of The Man Died with the Soyinka of “Kill the Religion.” Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar tells us that: “Cowards die many times before their death but the valiant die but once.” Our own Martin Luther King Jr., says it all in the following words: “The moment we are silent about the things that matter we begin to die.”

In the African context, a story is about “yesterday”, “today” and “tomorrow”, at the same time. According to the African theologian Jean Marc Ela from Cameroun, such a double “regard” or “view” of the past and the future requires fidelity to the past, to our “dangerous” memories and our pathetic and heroic memories. It also involves creativity to make new paths into the future with hope and optimism. This creativity is what Jean Marc Ela calls the “ethics of transgression” for the sake of epistemological rupture.” With that, Ela was able to create a new story, an African story in Christian theology and pastoral praxis. He triumphed over the warning of what the Nigerian author and novelist, Chimamanda Adichie calls “The Danger of a Single Story.” According to Adichie, the modern story of Africa is always replete with a single story. A single story of catastrophe and corruption: ‘But it is impossible to talk about the single story without talking about power. Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another, but to make it the definitive story of that person, the simplest way to do it is to tell the single story over and over again.’

The Nigerian problem is to be located in the right place where it belongs, namely, ‘the lust for power and domination by the privileged minority.’ This is what we should all struggle to tame and not religion in our nation. I rest my case!

Francis Anekwe Oborji is a Roman Catholic Priest. He lives in Rome where he is professor of missiology (mission theology) in a Pontifical University.

END

Be the first to comment