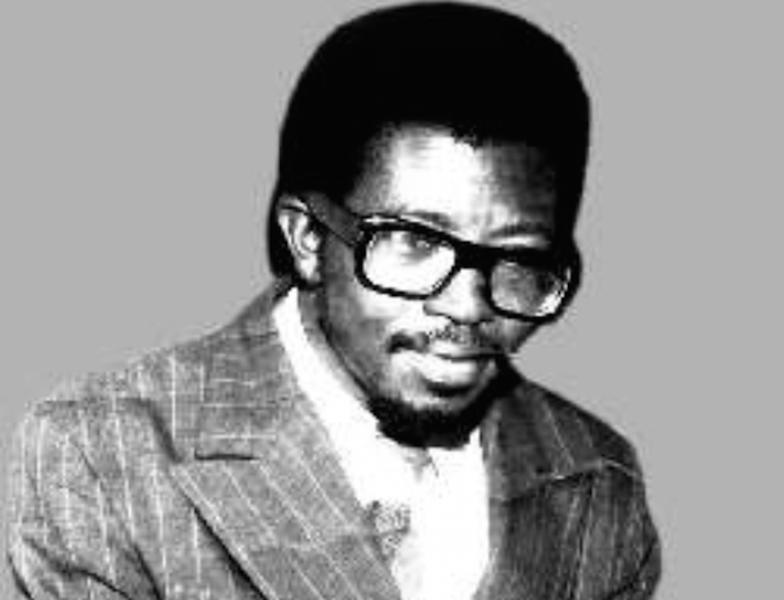

When the founding editor of London Review of Books, Karl Miller, died in 2014, many elegies were written for him by his poet friends. One of the poets, Richard Murphy, wrote that Miller’s “presence made the darkest day feel clear”. The testimonies of those who knew him intimately and the body of his work show that Soji Simpson’s presence also made the darkest day feel clear as a human being, a poet, a playwright, an actor and as a culture enthusiast. In Drama and Theatre in Nigeria: A Critical Source Book, Dr. Yemi Ogunbiyi, in his comprehensive and very insightful introduction, lists Soji Simpson as a member “of a different crop of playwrights, inadequately referred to as second generation playwrights”. His younger brother, Femi Simpson, who compiled and annotated Meditations: The Poems of Soji Simpson says that between 1965 and 1972, Simpson wrote five successful plays – Too Much Too Soon, The Vogue, If I forget Thee, His Master’s Voice and The Mirage, all of which were performed by The Neighbourhood Players, a theatre group which he founded. Soji Simpson kept many important records of this group – list of members, pictures of performances etc, etc. – even the list of members of Teeners’ Club which he joined during his Higher School Certificate’s days at King’s College, Lagos.

More than thirty members of the Neighbourhood Players subjected themselves to the rigours and discipline of rehearsals. They took themselves seriously even though they were in their late 20s and early 30s. These young men and women who were in different professions, were simply united by their love for the theatre and passion for literature in general. They played dangerously and gracefully. So totally committed to The Neighbourhood Players was Soji Simpson that he easily infected Gbadebo, Alaba, Idowu and Timi, his brothers and sisters, with his own enthusiasm.

The Neighbourhood Players, which ran between 1966 and 1968, also performed plays written by other writers. Bayo Awala, who was a very active member of the group, says in this book that, apart from some memorable productions of Soji Simpson’s plays, “We also tried our hands on productions by other writers. We were working with people like Segun Akinbola, Wole Amele, who really gave us a lot of insight into set building, stage construction and so on. Segun was an invited director, Soji was our “resident writer” because most of the productions we had were written by him, apart from the productions of Rasheed Gbadamosi’s Behold My Redeemer and Echoes from the Lagoon. Indeed, on August 8, 1974, when Soji Simpson went missing, it was during a rehearsal of Rasheed Gbadamosi’s play, Behold My Redeemer, at the National Museum, Onikan, Lagos. He was aged 35. Born in Lagos on April 8, 1939, he would have been 78 in 2017. Forty three years have passed since his sudden disappearance yet he remains, to friends and family, a devastating loss. For Soji Simpson was a bright light taken away too soon.

…he wrote about life after death, he wrote on Lagos life, on diligence, on the challenges of Nigeria’s flag independence; he wrote about Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe whom he called ‘Ogbuefi’, and, as if he was predicting his own painful exit, he wrote about death in the prime of life.

Before he became a playwright, poetry was his first mode of creative expression. During his secondary school years at Lagos Baptist Academy from 1955 to 1959 and his stint at King’s College for his Higher School Certificate, from 1960 to 1961, Soji Simpson distinguished himself as a powerful debater and poet. Bashorun J.K. Randle, Chief Femi Robinson and Professor Ekundayo Simpson, who were his contemporaries, testify in a section of Meditations, that he was a bookworm. In Bashorun Randle’s words: “He just loved books and would engage anyone in virtually all components of literature – plays, poetry, essays and book reviews. In addition, he had a riveting sense of history – both African and European, which enabled him to authoritatively quote verbatim resonant events together with precise dates that made him a champion in inter-house and inter-school debates. He was indeed a great and spell-binding orator”.

And Chief Robinson says: “Soji was an avid reader. He stood out like a teacher among us. You had to be reading one book or the other to be in Papa Simpson’s house. No fooling around”. He goes further to say that Soji Simpson, who represented Baptist Academy, “was always a threat to other schools at debates because he would prepare his brief just like a lawyer”. He was also a keen sportsman. Apart from ‘Simbo’, another nickname for him in school was ‘Miler’. He may be ‘self-contained’ as Bashorun Randle describes him but I suspect that just like many other members of Teeners’ Club, he must have been a smooth operator among the girls! More importantly, it appears that for him great writing was essentially a solitary, intellectual task.

We are told that he recited by heart all the 128 lines of Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” at the initiation night ceremony when he resumed at King’s College. On March 26, 1963, shortly after he completed his HSC at King’s College, he wrote to the editor of the West African Pilot, respectfully pleading with him to publish his poem on Nnamdi Azikiwe titled “Ogbuefi”. That was when Dr. Azikiwe was the Governor-General of Nigeria. We do not know whether West African Pilot published the poem or not, or whether the editor replied him or not. What we know is the striking thing he said in that letter: that his life ambition was to be a poet and a playwright. That was in an age when the fashionable professions were Law, Engineering, Medicine and Accounting and Finance. He cared deeply about writing and ideas.

It was during his years at Lagos Baptist Academy and King’s College, Lagos, that he wrote about 81 poems, seventy three of which are compiled and annotated by Femi Simpson. It is remarkable that about thirty of these poems are love poems in which the poet-persona is very romantic. The poems were not written in dense metaphors that encase complex layers of meanings. They are just verses of careful observations, wise sayings and lovers’ ditties. This collection of early poems by Soji Simpson may therefore be described by some lovers of highbrow poetry as juvenilia because he was not fully formed as a poet when they were written, but they have their literary strengths and values. To borrow Niyi Osundare’s lines in Songs of the Marketplace, Soji Simpson’s poetry may not be the esoteric whisper of an excluding tongue, his poetry may not be a claptrap for a wondering audience, it may not be a learned quiz entombed in Greco-Roman lore, all the same, it has its own life-spring. This life-spring reflects all the rays of light that his gift and talent and humanity radiated.

It was during his years at Lagos Baptist Academy and King’s College, Lagos, that he wrote about 81 poems, seventy three of which are compiled and annotated by Femi Simpson. It is remarkable that about thirty of these poems are love poems in which the poet-persona is very romantic.

In his poetry, sincerity and tenderness survive. Since it has taken the Simpson family twenty five years to decide whether to publish this commemorative collection or not, there is a sense in which its publication is a form of redemption itself. Perhaps the presentation will help friends and relations come to terms with the tragedy of his disappearance. Hilton Als, the theatre critic of The New Yorker, published an essay on March 17, 2017, titled “Derek Walcott, A Mighty Poet, Has Died”. It was one of the moving tributes to the St Lucia’s Nobel Laureate who died at 87 last month. Among other things, Hilton wrote: “What better way is there to memorialise writers than to read what they have written, and remember who they were in all those works they were brave and confident enough to imagine in the first place.”

It is gratifying that we are remembering Soji Simpson with a part of him that is not missing, a part of him that is a living testimony to his talent and exertions, a fitting tribute to a conscientious thespian. Femi Simpson, the compiler worked under the guiding light of his brother to get us to read the poems, listen to the sounds and melody they make, and derive pleasures in their meanings and significance. What were the subjects that attracted Soji Simpson’s attention? How did he write about them? In other words, what were the strategies of his production? He was largely influenced by William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley and William Blake – all romantic poets. He was also influenced by William Shakespeare, John Milton and the Italian scholar and poet, Francesco Petrarca. To be sure, he obviously learnt the rhyming tricks and techniques—without their compelling and enduring tropes—from these masters. He must have untangled their lines, scrambled them, inspired by them.

Soji Simpson imbibed many of the elements of romanticism as a literary movement: their focus on the writer’s emotions, celebration of nature, beauty, idealisation of women, children etc etc. We can therefore easily argue that in this collection published by Lanre Idowu’s Diamond publication Limited, he is more of a romantic poet. He wrote passionately on love of women, on patriotism, hardwork, time—the unstoppable cycle of human existence and stupidities, tribulations and triumphs; he wrote about life after death, he wrote on Lagos life, on diligence, on the challenges of Nigeria’s flag independence; he wrote about Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe whom he called ‘Ogbuefi’, and, as if he was predicting his own painful exit, he wrote about death in the prime of life.

It is gratifying that we are remembering Soji Simpson with a part of him that is not missing, a part of him that is a living testimony to his talent and exertions, a fitting tribute to a conscientious thespian.

He wrote on the general complexities of life, on mouth-watering Nigerian food, on depression and desolation, on the vagaries of nature; he wrote about the challenges of keeping New Year resolutions, on Lagos Baptist Academy and King’s College, Teeners’Club, on death as agent of oblivion, and the difficulties of parting from our loved ones; he wrote on his strong faith in God, and like a preacher, he wrote about the importance of humility. He wrote to celebrate the birthday of his brother, Dayo and he paid tribute to Tinuke, one of his sisters, when she gained admission to Methodist Girls High School, Lagos. He also wrote poems on his great affection for the arts. These poems are rendered as ballads, lyrics, odes, sonnets and elegies.

Femi Simpson explains the making of many of the poems. He does not only talk about the themes but in fact dwells elaborately on the style of each of the poem like those very good teachers of literature in those good old days. Finally, in so many ways, then, he shows that his brother’s poems urge a more contemplative view of life.

Kunle Ajibade, Executive Editor of TheNEWS and P.M.NEWS, is author of the award-winning Jailed for Life: A Reporter’s Prison Notes and What a Country!

END

Be the first to comment