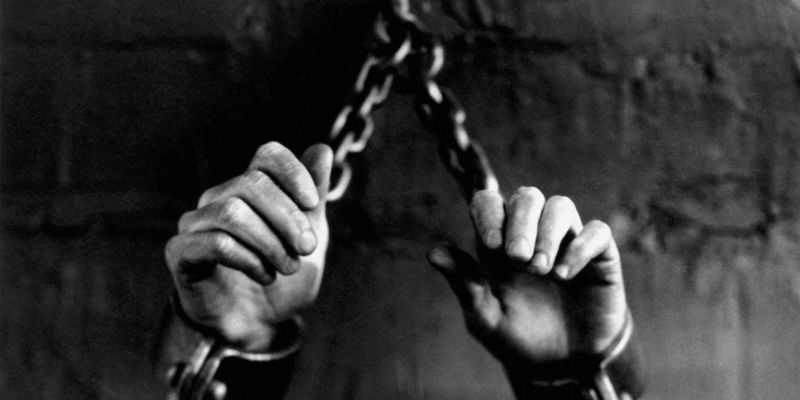

Has slave trade ever been really abolished? Many would give an emphatic ‘NO’ as their answer to this question. Surely, the intensity may have been reduced and the anguish associated with the trade may have been drastically scaled down, particularly in proportion to the explosion in world population, but the trade in human cargo or human trafficking, which is now a euphemism for slave trade still thrives till date.

The present slave traders are different because the ancient ones have long passed on and their strings of successors may have moved to more lucrative areas. In fact, if you can lift oil for good dollars, why would you want to engage in the more dangerous task of lifting human elements? Again, today’s slave trader and his article of trade are mainly domiciled within the indigenous population.

In both ancient and modern times, the motivation in slave trade has been economic – the simple lucre for blood money. Kwame Nkrumah (1909-1972) shows by happy illustration that the best way of looking at the present and the future is a peep into the past, hence the imperative to take a short excursion into the history of the slave trade. After the agrarian revolution, the labour-intensive agriculture of the New World demanded a large workforce.

The cultivation of crops like sugar cane, tobacco and cotton required an unlimited and inexpensive supply of strong persons to ensure timely and uninterrupted production for the European markets.

Slaves from Africa offered the solution. The slave trade between West Africa and the Americas reached a peak in the mid-18th century, when it was estimated that over 80,000 Africans crossed the Atlantic annually to spend the rest of their lives in chains.

Of those who survived the voyage to the final destination, approximately 40 percent ended up in the Caribbean Islands; 38 percent ended up in Brazil; 17 percent went to Latin America; and five percent ended up in the United States of America.

From time, slave trade has been a lucrative business. History books are replete with the fact that a slave purchased on the African coast for about £14 in bartered goods in 1760 easily sold for £45 in the American market. The slave’s journey to a life of servitude often started in the hinterlands of Africa with his or her capture as a prize of war; or as a tribute given by a weak tribal state to a more powerful one; or by outright kidnapping by local traders.

European slave traders rarely ventured beyond Africa’s coastal regions as the interior part of Africa was riddled with diseases; and there was no telling when the natives could turn hostile. That’s why the Europeans preferred to stay in the coastal regions and have the natives supply the slaves to them. As soon as the canoes carrying the slaves arrived at the trader’s landing place, the purchased Negroes were cleaned and rubbed with palm-oil to look fresh and presentable.

On the following day, they were exposed for sale to the captains. At this point, the European purchasers first examined the Negroes relative to their age.

They then minutely inspected their persons and did a thorough check into the state of their health. Those of them afflicted with any infirmity, deformed in any way; those that had bad eyes or teeth; or if they were lame or weak in their joints; or those that were slender or narrow in the chest; or if they had a history of past affliction that could render them of less value in the labour market – these were all rejected.

If we had such meticulous inspection and high rejection rates for the cattle and other live-stock coming to us from Northern Nigeria, many of them would have arrived safely at the Southern markets.

In any case, the Negroes that finally received the stamp of approval were taken on board the ship the same evening.

The rejected Negroes were treated as rejects – beaten and tortured with the rage of a man who saw the loss of revenue staring him in the face. During the voyage, the slaves were kept in the ship’s hold, crammed together like sardine, under very squalid conditions; and many of them that could not survive the journey became food for sharks.

At the plantations, slaves were treated as beasts of burden and subjected to all forms of inhuman treatment. In large part, slavery undermined local economies and political stability as villages’ vital labour-forces were shipped overseas as slaves. Quite often, kings and chiefs sold criminals into slavery so that they could no longer commit crimes in their communities. In 1807, the British Parliament enacted an Act abolishing slave trade throughout the British Empire; but slavery still flourished in the British colonies until its perceived final abolition in 1838.

In the letters of the law, slavery is no longer legal in any part of the world.

But its modern mode, human trafficking, remains an international problem. It is estimated that about 29.8 million people are living in illegal slavery today.

A week ago, precisely on August 4, 2016, a United Kingdom crown court sitting Isle worth sentenced a Nigerian woman, Franca Asemota, 38, to 22 years imprisonment after finding her guilty of attempting trafficking in persons for sexual exploitation.

Asemota who was identified as a trafficking suspect in 2012 fled from Italy to Nigeria when some of her co-conspirators were arrested by Immigration Enforcement investigators.

The head of the Immigration Enforcement crime team, David Fairclough, described Asemota as the “lynchpin of a trafficking ring which targeted vulnerable young women in Nigeria, promising them brighter future working in Europe… only to sell them into prostitution”! By whatever name called, slave trade is evil.

It can only be curtailed with stern laws and rigorous enforcement – the type of enforcement that provided no hiding place for Asemota and her co-travellers as the British authorities were prepared to pursue such even into the deepest hole. It can’t be done otherwise!

END

Be the first to comment