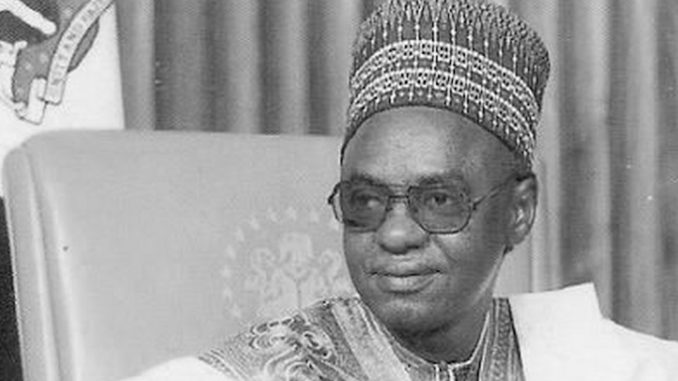

AS usual, encomiums have been pouring in for the late Shehu Shagari, Nigeria’s first Executive President, who died last Friday after a period of ill-health. At 93, he could be said to have died a fulfilled man, considering his earthly journey that saw him rise from a humble beginning as a teacher to occupy the highest office in the land. In a country where life expectancy at birth is put at about 55 years, he was also a man blessed with longevity.

After his training as a teacher, Shagari was elected to the Federal House of Representatives before serving as the Parliamentary Secretary to the late Prime Minister of the country, Abubakar Tafawa Balewa. Then came a string of ministerial appointments under the civilian and military administrations. However, to many, it is his role as the President of Nigeria (1979-1983) that will define his legacy. It is a role that was thrust on him more by accident than design. Although he had featured in Nigerian politics in the run-up to the country’s independence in 1960, chalking up appointments, which could have prepared him for a higher calling, he never wanted to take part in government beyond being a senator until “a no-nonsense delegation” from Sokoto got him nailed. According to him, “the implications of my saying no, which they defined as meaning denouncing them, was that I would have to give up politics completely, which I didn’t, because I still felt I should try to influence policy from outside government.”

But, as fate would have it, the reluctant candidate was able to upstage more colourful aspirants to land the presidential candidacy of the National Party of Nigeria, the party that inherited the government from the military. After winning the election, he had a unique opportunity to shape the trajectory of Nigeria as the leader of Africa’s most populous country awash with oil money, which made many to consider the country as the richest on the continent.

In spite of their dictatorial tendencies, the military bequeathed several noteworthy legacies to the incoming Shagari administration in 1979. Then, Nigeria had a relatively buoyant economy and thriving state-owned enterprises, including the Nigeria Airways Limited, which had 32 aircraft, and the Nigerian National Shipping Line, which owned 19 new ships. Another potential success story Shagari inherited was the Ajaokuta Steel Company Limited project, which he met at the foundation stage. An integrated enterprise, the ASCL was envisaged to kick-start Nigeria’s industrial revolution and eventually offer employment to about 500,000 workers. But the Shagari-led NPN Federal Government blew it all.

First, the economy. For the exchange rate, the naira was relatively stronger than the American currency: N0.59 exchanged for $1, meaning 59K would fetch $1 in 1979. However, inflation was 11.7 per cent and Gross Domestic Product stood at $47.2 billion, according to World Bank data. The 13 years of military rule achieved notable infrastructure development, including the Lagos-Ibadan Expressway (1978), the seaports infrastructure in Lagos, Warri, Port Harcourt and Calabar; the National Stadium, Lagos, the National Arts Theatre, Lagos and expansion of roads and bridges across the nation.

In 1979, Nigeria had a booming textile industry, which was the highest employer of labour. With this development, Nigeria stood in a good position among her peers in the developing world. Then, Nigeria competed favourably with the like of Malaysia, Singapore and Brazil. The pre-Shagari era witnessed mobility in employment, whether for the highly skilled graduates, the semi-skilled or artisans. Graduates had employment opportunities up until 1982, when the economy started going awry.

But Shagari’s government could not deliver on its promised Green Revolution, though it spent heavily on the river basin development authorities, dams and irrigation. The brave efforts of experts and technocrats to transform the country soon ran into the wall of corruption and patronage, which the ruling party and government erected.

Instead of truly diversifying the economy it inherited, it deepened the country’s dependence on oil. According to OPEC data, prices that had jumped from an average $2.7 per barrel in 1973 averaged $11pb in 1974 to trigger the first oil boom, $12.79pb in 1978, and gifted Shagari with about $30pb in 1979, $35.5pb in 1980 and hitting $40 in 1981. The regime went on a spending spree, depleting the external reserves from an average of $6 billion in 1979 to a paltry $1.2 billion as of January 1984.

To its credit, it pursued the steel projects, but ruined it by poor judgement and by siting the steel mills based on political, rather than rational economic considerations. The Country Studies report of the United States Library of Congress recalled that, “for political reasons, government spending continued to accelerate and frictions… only reinforced financial irresponsibility.” Foreign debt rose from N3.3 billion in 1978 to N14.7 billion by 1982, at a time $1 exchanged for less than N1. The then 19 states had ratcheted up a combined N13.3 billion in debt by 1983. GDP per capita (at current value) fell from the $662 it inherited in 1979 to $446.1 by the time it was overthrown in 1983, according to the World Bank’s World Development Indicators chart. GDP also fell from $61 billion in 1981 to $51.39 billion in 1982 and $35.45 billion in 1983.

A fall in oil prices by mid-1981 exposed the incompetence of the government; it restricted public sector recruitment and borrowed furiously. It also expelled about two million foreigners, one million from Ghana alone, ostensibly to make way for Nigerians to secure jobs. Corruption in the issuance of import licences deprived businesses of critical raw materials, machinery and spare parts and, on the other hand, caused a scarcity of “essential commodities” – notably rice, milk, sugar, vegetable oil – that the succeeding military regime tried to address by direct distribution. Rice imports rose from 50,000 tonnes in 1976 to 651,000 tonnes in 1982. Warnings on impending economic adversity and calls for action, including one by leading opposition figure, Obafemi Awolowo, were met with venomous verbal attacks. Projects like the national housing scheme and airports were also driven by politics, thus leaving abandoned construction sites across the country.

It was under the administration that, for the first time in Nigeria’s history, securing employment, once effortless, became difficult for university and polytechnic graduates. Between 1979 and 1983, $14 billion worth of capital left the country, said a USLC report, reflecting loss of investor confidence in the economy. Major corruption scandals emerged at the Nigerian National Supply Company, Federal Mortgage Bank, Federal Housing Authority, CBN, National Youth Service Corps and Federal Capital Territory Administration, where a contract binge took place. While the economy floundered, government ministers competed to amass wealth and flaunt private jets, branded champagne and luxury cars.

On his watch, Nigeria Police Force transformed to a strike force of the ruling party. The massive rigging of the 1983 elections became the administration’s albatross. The ship of the state finally hit the rock as Awolowo predicted. As President, Shagari was neither a visionary nor a radical thinker. Little wonder that when he was toppled on December 31, 1983, he was enveloped in an aura of failure.

Though the Shagari’s administration was toppled, the four-year rule had laid the foundations for the elite’s unconscionable looting of the national treasury. This resulted in slow economic growth rate, balance of payment crisis, mounting national debt and debt-servicing burden, deepening food shortage crisis, the collapse of the manufacturing sector, mounting unemployment, galloping inflation and deteriorating standard of living.

It is a sad commentary on our collective intelligence that those who are never prepared for the most exalted public office in the country, with very little or nothing to offer, have continued to bestraddle the country’s leadership. Nigeria is the worse for it, evident in its economic backwardness since 1979, despite its abundant human and material resources.

However, both in private and public life, Shagari exuded modesty, humility and a gentlemanly grace. What did not come naturally to him were the traits of a visionary who must be clear-headed and tough-minded with a thorough grasp of critical issues. For this, the Nigerian people are still paying the price.

END

Be the first to comment