Adaobi’s family should go beyond the annual singing of Psalms for forgiveness and endow scholarships for the children of their estranged family – descendants of the adopted Nwaokonkwo. Education is the key to lifting the poor from poverty. The reason why a widow died and her children died mysteriously could be due to infections in a country where the life expectancy is 50 years.

Adaobi Nwaubani narrates in the New Yorker the fact that there is hurt in every family that is self-inflicted. Having the humility to confess past wrongs and ask for forgiveness is part of the healing. Having the courage to forgive those who wronged you frees you from the resentment which Mandela called a poison that you take and hope that it kills your enemy. Desmond Tutu teaches that there is nothing that is unforgivable and there is no one who does not have something to be forgiven about. Africans have forgiven the unforgivable crimes of 400 years of slavery, 100 years of colonisation and 70 years of apartheid but some Africans still find it difficult to ask for forgiveness or to forgive members of their family for past wrongs. What Adaobi described is going on all the time in Igboland where the belief in witchcraft is not as pronounced as in some other cultures. Instead of hunting for witches to blame for your misfortune, the Igbo are encouraged to look inward and see if there are things that need atonement for or to ask their Chi for a better deal. Adaobi’s family did not kill or exile the adopted child of an enslaved ancestor but forgave him, even after he was suspected of plotting to poison a leader of the family. Okonkwo was also told off by Achebe for killing Ikemefuna, a child that called him ‘Papa’, just because an oracle told him to do so. The Igbo have no history of raiding their neighbours for slaves or executing genocide to colonise their land. They believe in letting the eagle perch and letting the kite perch.

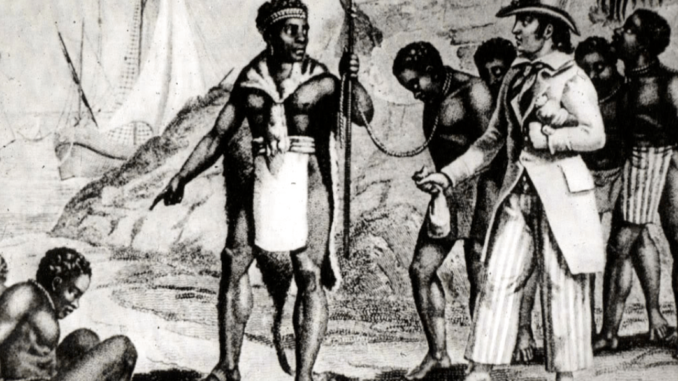

Igbo culture, like all cultures, is not perfect. Culture is not defined as a way of life, contrary to colonial anthropology. Culture is defined by Cabral, Ngugi, Hall and James as a struggle between the forces of domination and the forces of liberation. The way poor people live under capitalism, the way women live under patriarchy, and the way that black people live under racism are not the ways they chose to live but represents the conditions they did not choose; conditions imposed on them by law and tradition, under which they struggle to make history. The Osu and Ohu emerged among the Igbo as a consequence of 400 years of being raided as prey during the European trans Atlantic slavery that cost an estimated 100 million lives to Africa, according to Du Bois. The Igbo, unlike their neighbours, had no kings and chiefs, nor did they have standing armies to defend themselves against slave raiders and kidnappers or with which to raid their neighbours; and that was why they were the predominant group of people captured for sale from what Europeans called the slave coast, according to Douglas Chambers’, Murder in Montpelier: The Igbo Africans In Virginia. Despite the blight of the Ohu and Osu on the egalitarian Igbo system of direct democracy, the fact remains that the Igbo survived the impacts of the slave raids, colonialism, and post-colonial genocide very remarkably. “We are survivors”, sang Bob Marley and the Wailers.

The question that Adaobi is raising is the old one of how could Africans sell their own into slavery? This was the question that Walter Rodney tackled in his doctoral dissertation on the “History of Upper Guinea Coast.” He concluded that what happened during the 400 years of the African holocaust was the process of class formation and primitive accumulation. The few chiefs who sold fellow Africans did not regard the war captives as their own people because they belonged to a different class or to a different nation. It was not a trade of the sort where parents put their own children on the shelf to say that these ones are toro-toro, those ones are shishi-shishi, and those other ones are nai-nai pence. It was a long-running war of pillage and the hunting of labour in black skin that Marx condemned in Das Kapital. It is true that some African elites benefited from the enslavement of Africans, just as some African elites continue to benefit from the looting of African resources today. But the vast majority of the Igbo and other Africans have always been activists against oppression and the main beneficiaries were Europeans, from royal families down to pirates. The fact that the wounds of slavery are slow to heal in Igboland is evidence that the Europeans still owe reparations to the survivors of the European slavery. Adaobi’s family is showing the way by apologising to those they hurt in their family and asking for forgiveness from the ancestors. When will Europeans make atonement for crimes against humanity?

It is high time that the African states joined the demand for reparations, even while recognising that, like all human beings, we have also hurt ourselves in our struggle for survival and we should ask for forgiveness, in the way that Mathieu Kérékou visited an African American church, knelt down and asked for forgiveness for the role of Dahomey in the capture and enslavement of fellow Africans.

Another Guyanese writer, Karen King, posed the same Rodneyian question in her novel, The Hangman’s Game, in which a Guyanese professor of linguistics who was married to a Nigerian and who lived under a brutal military dictatorship that was killing fellow Nigerians with impunity, posed the question in the novel: How could Africans sell their own for 400 years? In the novel, her Nigerian husband retorted by asking, how could she write a novel today about a slave rebellion and still make the enslaved lose instead of giving them victory in her fiction? She protested that it was a historical novel but her husband encouraged her to revise the history. The pain of the African Diaspora is real and sometimes I get it from students in the U.S. or in the Caribbean, were you not those who sold us? To which I would answer that I would never have sold anyone, I would have been among the warriors and freedom fighters who did fight back with sticks and stones against guns to try and save us from being captured as Olaudah Equiano narrated and as Rodney documented in historical accounts written by even some Europeans.

Chinweizu, in The West and the Rest of Us, disputes the 419 propaganda by the British that they came to fight against slavery in Arochukwu, which was why they burnt the Long Juju. Chinweizi said that was not true because by that time, the slave trade that the British and other Europeans initiated had come to an end and the British were only after the trade in palm oil, which they wanted to monopolise in order to dictate prices against the interests of the middlemen in the interior. It is true that there are always saboteurs and collaborators in any system of oppression, especially one that lasted for more than 400 years, but it is not smart to blame the survivors for the massive crimes against humanity committed by Europeans against Africans. Frantz Fanon said that Europe owes massive reparations to people of African descent at home and abroad. Chinweizu also agrees that reparations are due since people of African descent appear to be the only survivors of historic wrongs that have not been offered any form of reparations and not even apologies, simply because of racism.

Adaobi played into this by starting her opinion with a doubt about whether Africans deserve reparations, given that Africans, like all human beings, have also hurt one another. Africans never traveled thousands of miles to enslave others for 400 years and colonise the survivors for another 100 years and ridiculously turn round to say that Africans owe them billions, according to Ekwe-Ekwe in Africa 2001. In Specters of Marx, Derrida agreed that Africans deserve to have the unpayable international debts cancelled. It is time for Europe to start paying back the debts owed to Africa and the Caribbean countries are demanding such reparations from European enslavers. It is high time that the African states joined the demand for reparations, even while recognising that, like all human beings, we have also hurt ourselves in our struggle for survival and we should ask for forgiveness, in the way that Mathieu Kérékou visited an African American church, knelt down and asked for forgiveness for the role of Dahomey in the capture and enslavement of fellow Africans.

Gates never asked a similar question of the white BBC crew or of any white person he met, that how does it feel to work with the descendant of those that your ancestors enslaved? Many poor whites resent such questions and claim that they did not benefit directly from slavery. Yet it was poor whites who fought the American civil war to keep slavery going…

The vexing question was posed repeatedly by Henry Louis Gates in his infamous documentary for the BBC, Wonders of the African World, where he asked market women in Ghana what it felt like to meet a descendant of one of those that her ancestors sold into slavery. Gates never asked a similar question of the white BBC crew or of any white person he met, that how does it feel to work with the descendant of those that your ancestors enslaved? Many poor whites resent such questions and claim that they did not benefit directly from slavery. Yet it was poor whites who fought the American civil war to keep slavery going and it is poor whites who join the KKK to terrorise the survivors of slavery today in defence of white privilege. Reparations for slavery will not come out of the pockets of poor whites but would be paid as percentages of the GDP, which would have gone to corporate welfare and not necessarily to the poor. Europeans and North Americans should follow the example of Adaobi’s family and ask for forgiveness from Africans, they should offer reparations too.

Adaobi’s family should go beyond the annual singing of Psalms for forgiveness and endow scholarships for the children of their estranged family – descendants of the adopted Nwaokonkwo. Education is the key to lifting the poor from poverty. The reason why a widow died and her children died mysteriously could be due to infections in a country where the life expectancy is 50 years. Adaobi’s cousin was right that this sounds like the story of the bogeyman, with which naughty children are warned to eat their greens or else. Africans should invest more in research to find cures for tropical diseases instead of simply praying for forgiveness for past wrongs. Families that educate their sons and daughters to the highest levels tend to thrive better whether they are Ohu, Osu or Amaala. Education is the key to the healing of the wounds of slavery in Africa.

With more emphasis on education for which the Igbo are the leading achievers in Nigeria, people like Adaobi will make friends with more school mates, irrespective of their family backgrounds and Adaobi may learn the Igbo language enough to understand the meaning of names. Her family name, Nwaubani does not mean someone from the coastal area, it is the name of King Ja Ja of Opobo whose name was really, JoJo Ubani or someone who was wealthy in real estates: Uba is wealth and Ani is land. Similarly, the name of the town that they changed, Umuojameze, does not mean that the oracle is king. On the contrary, it means that the children of the flute, Oja, know no king, Ama eze. It is the Igbo egalitarian philosophy that the Igbo know no king but it is understandable that after the military imposed chiefs on Igbo communitiues in 1976, those who wanted to be kings might be embarrassed by a name that said that the Igbo know no king.

Biko Agozino is a professor in the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences in Virginia Tech, USA.

Originally published in massliteracy.blogspot.com.

END

Be the first to comment