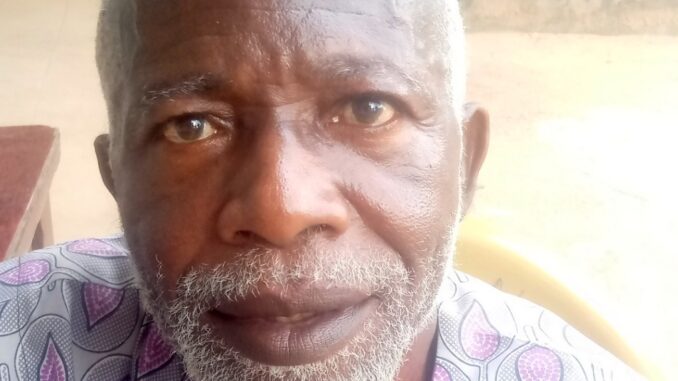

A veteran journalist, Okharedia Ihimekpen, who is in his late 60s, compares journalism as practised in the past and present, among other issues. In this interview with PREMIUM TIMES, Mr Ihimekpen, who started his career with the Nigerian Observer, talks about the brown envelope syndrome and journalism during the military era.

PREMIUM TIMES: How would you describe the practice of journalism in your time and now?

Okharedia Ihimekpen: I entered this precarious business of journalism in the early 70s. In our heydays of yore, things were not as bad as it is now. Although it was rough then, we now have what we call digital journalism.

In those days, when you are going for an assignment, you will need a photojournalist, a car and a driver. So, you go as a crew, but today just one person can go for an assignment and he does the job of a crew with the help of your smartphone.

You can even start sending your stories while the event is ongoing. There is a paradigm shift because this was not what was obtainable in those days. So, it now depends on how people can cope because the world is not static, it is dynamic. Since society is always changing, we have to change with it and that is the only way you can survive it.

PT: Has this paradigm shift also affected the ethics of journalism?

Ihimekpen: Yes, it has. These days when journalists go for assignments, they wait for brown envelopes. We did not grow up that way. The brown envelope syndrome came in at about the late 80s and early 90s.

When I started practising journalism, we did not seek brown envelopes. We practically begged people for news. You are paid when you write an article for a newspaper and that encourages you to write more. You put in the effort to get news and you must have the nose for news.

But these days, apart from a few dedicated journalists, the majority stay in one place and when they cover an assignment, they expect something.

Read Also

Coronavirus: Nigeria records 169 new cases, zero deaths

Lagos Bye-Election: PDP candidate reacts to allegations of certificate forgery

BCDA claims payments to officials’ personal accounts ‘legitimate’, despite violating law

I am not saying there (wasn’t) then, but it was not like this. Journalists of then were like scavengers, people hardly liked them, but they were feared.

Journalism will not make you rich but it will open doors for you. When you walk into a gathering and introduce yourself as a journalist, they will immediately change the topic of discussion and sometimes walk away from you because they do not like you.

The journalists, too, were not interested in good stories because they believed negative news was the story. That was the period we just came out from the nationalist struggle by Obafemi Awolowo, Nnamdi Azikiwe, and Peter Enahoro, popularly known as Peter Pan. We felt then that the only way we could make our name is to write stinkers. We were used to ‘write and kill.’

Most times then, ours was to investigate the dirty side of government or big individuals in the society. You look for a loose end and when you can unravel something new, you are a hero. I recall one of our correspondents in Rivers State went to cover Diete Spiff’s birthday but came out with a negative story on Mr Spiff’s wife. They (Spiff’s family) were annoyed with the story so they got the reporter, beat him, and used a broken bottle to shave his hair and that instantly became the real news all over. The story became too hot that the then Head of State, Yakubu Gowon, had to intervene and they paid heavy compensation. They paid us (Nigerian Observer) huge compensations. But these days, when you talk, your colleagues will want to blackmail you.

PT: But we later shifted from ‘publish and be damned’ to developmental journalism. At what point did this happen?

Ihimekpen: That should be in the early 80s. We felt we cannot remain the same way forever. We started seeing it from the angle of partnership and also protecting our lives. It was at that point too that the military started giving some carrots. When some journalists started getting these carrots, we felt we could improve ourselves.

So, people like Peter Pan, who was my mentor, whom I described as someone who has written so much on earth and torn the sky with his pen…. he was the Editor-in-Chief of the old Daily Times at the age of 21.

Although the military was throwing the carrot, they were also very hard and when you are caught, they will be hard with you.

PT: How did brown envelopes become a common feature in journalism?

Ihimekpen: It was the encroachment of the military ideology, military mentality, like that of the former military president, Ibrahim Babangida, for instance, who was so strong that he was able to ‘oligopolise’ all the institutions in the economy.

When there is negative news, he felt he could buy his way through. In the early 80s, I was with the Esama of Benin, Gabriel Igbinedion, in one of his business conglomerates, Okada Air. They brought some aircraft and one of his sons organised a ceremony to launch the new fleet.

He proposed that money should be given to journalists who came to cover the event, but I told him that it was not necessary. I told him to wait and appreciate whoever does any good report. He rebuked me and went to report me to his father. The father told me that I wanted to destroy his business, he told his son to give money to the journalists. I told him that I would not be part of what they planned to do.

The event came and they shared the money with journalists. One small newspaper in Lagos called Lagos News and New Nigeria, who did not get from the largesse went to do their write up. They described the new fleets in Okada Airline as refurbished aircraft. You know the negative news is the main news and their report overcrowded other news reports.

The then Minister of Aviation, Jeremiah Useni, had to query the airline over the refurbished aircraft. They (management of Okada Air) started running helter-skelter and their father (the Esama of Benin) realised the usefulness of my advice and called me to come and establish The Speaker, a newspaper. So, you will find out that the brown envelope was good and bad. If well managed, it could be good for you but when badly managed, it could be bad.

PT: Would you say the gratifications that journalists receive today in the form of brown envelopes is good?

Ihimekpen: No, it is not because it has turned journalism into ridicule. For instance, I will not encourage someone to become a journalist now because it will not make you rich. Brown envelopes have become what some journalists survive on. It is an unfortunate situation and one of the publishers of a leading newspaper in Nigeria (name withheld) once told me that he does not need to pay journalists that he employed because he believes that his company’s identity card has given you the window to make money.

This is someone who read English from the University of Benin and was groomed in the Nigerian Observer. The brown envelope has helped to reduce, diminish, and denounce journalism, and sometimes you are not treated softly and nobody takes you seriously anymore. It has also made a few good journalists lazy because they have become copy and paste specialists. People will go for an assignment and only one person will write the story and they make the mistake of sending the story to their head office with that person’s by-line. There is also the political aspect of it by the Nigeria Union of Journalists (NUJ) who admits all sorts of persons because of elections.

PT: In your heydays, you found your way into the sickbed of the late Ambrose Alli, a former governor of defunct Bendel State at the University College Hospital (UCH) in Ibadan, despite serious military protection. How were you able to do that?

Ihimekpen: That period, I was still writing for the Nigerian Observer in Benin City. When he was arrested and being tried during the era of Muhammadu Buhari, we felt it was a case of natural injustice.

His offence was that he signed on his complimentary card and that was when people became wary of writing at the back of the complementary cards. The late governor, Ambrose Alli, wrote something at the back of his complimentary card and gave it to Gabriel Enaboefo, the then Director of Organisation of the defunct Unity Party of Nigeria (UPN) in the state. The card permitted him to collect a particular sum of money from a contractor for the party. It was less than N1 million.

After using it to collect the money, Mr Enaboefo retrieved the complimentary card and kept it. So, when he was arrested during the military era, to defend himself, Mr Enaboefo presented the complimentary card as his defence that he did not steal any money.

It was that money that was used to rope Ambrose Alli in that matter and his security votes. The former governor tried to defend himself but they did not listen to him but eventually, he was sentenced.

Same with the late Bola Ige and other civilian governors in the botched Second Republic. Initially, we were seeing Mr Alli during their trial in Lagos, but suddenly we were no longer allowed to see him. They brought Mr Alli, the late Abubakar Rimi, Alex Ekweme, and others to Agodi Prisons and Mr Alli fell ill in the prison and was brought to UCH.

Some of us, including Omo Ikhiroda, Sam Iredia, and I would go to UCH to try to see Mr Alli, we would not be able to see him. We learnt his health had deteriorated. Mobile police and soldiers were always guarding his hospital room. After some time, we started monitoring the movements of all the personnel around the hospital, including the security people and we found a loophole. We took advantage of it.

I mastered how to use the camera and after one week of practice, I got dressed in a medical doctor’s robe and went into Mr Alli’s room. Mr Alli was shocked to see me because he was not expecting anyone at that time, I told him to be calm, and he recognised me.

I took several pictures of him and asked a few questions, he responded. He was very apprehensive. I took five different shots and left. I met the soldiers outside drinking and cracking jokes. We left for Lagos immediately. We gave the pictures to Tribune and some other media. By the next day, it was a front-page story, “Alli on the line, counting hours.” Other newspapers copied it. By the third day, there was a riot in Ekpoma as students started criticizing the state Mr Alli was in.

The military authorities tried to find out who the reporter was. They saw that it was not fiction and that Mr Alli even talked to me. We were declared wanted by the military. But the whole idea paid off because they changed all the security men and they set up a committee which recommended that Mr Alli should pay back some money and be set free.

The same leverage was extended to Bola Ige and others.

It was the Esama of Benin, Gabriel Igbinedion, who eventually offset the money for Professor Ambrose Alli, through some arrangements. That was how Mr Alli was let off the hook.

PT: Do you think journalists of today in Nigeria can take that kind of risk?

Ihimekpen: No, they are not daring. Although there is still some form of investigative journalism, those that will put the life of the journalist at stake is no longer done. The wife or husband of the journalist will even query him/her.

PT: How can we change the face of journalism?

Ihimekpen: Unfortunately, journalism has become a dumping ground for graduates. In those days before you are employed as a journalist, you write feature stories which they use to judge those who are qualified to practice. The use of English, syntax, and presentation, among others. But now these are not there today. The field has become one for all comers. So, I think the situation should be reversed.

END

Be the first to comment