A return to the 12-state structure of 1967 is the best option open to Nigeria at this time.

Introduction

Since the Abacha confab, there have been loud and persistent calls for the restructuring of the Nigerian federation. The most strident voices have been from the South, while the Northern voice has been more muted. This has created the impression that the South is for and the North is against restructuring. The challenge for the North is that there has been a long break in its reflections on what it wants and this memo sets out to propose a path to and an outcome of restructuring that serves the interests of both the North and Nigeria as a whole.

In 1991, a group of politicians, intellectuals and technocrats from Northern Nigeria held several meetings in Kaduna and Kano to design and propose a new federal structure for Nigeria. Among members of this group were Alhaji Sule Gaya, a former first republic minister, Alhaji Tanko Yakasai, Chief Sunday Awoniyi, Dr. Suleiman Kumo, Dr. Ibrahim Datti Ahmed, Dr. Mahmoud Tukur, Mallam Sule Yahaya Hamma, Alhaji Abdullahi Maikano Gwarzo and others. They came up with various constitutional, political and fiscal alternatives and options with which to negotiate with the rest of Nigeria in restructuring the federation. They invited Chief Anthony Enahoro to Kano, held discussions with him and agreed to pursue a restructuring agenda together, only for the Chief to rush to Lagos to hold a unilateral press conference to launch an agenda for restructuring under the Movement for National Reformation.

In 2003, after twelve years of advocacy without making headway, Chief Enahoro decided to return to the same group to continue the discussions he abandoned in Kano. The 2003 discussions held at a meeting room in Sheraton Hotel, Abuja with participants such as Mallam Adamu Ciroma, Alhaji Umaru Shinkafi, Alhaji Mahmud Waziri, Prof. Ango Abdullahi and others in attendance. The Chief narrated the contours of his journey in pursuit of restructuring since 1991 and outlined the results of his consultations within the three zones in the South. He wanted the three zones in the North to each outline their own positions, so he could have an overall picture of the positions of the six zones in Nigeria.

Having listened to the Chief’s submission, the group referred him to the Arewa Consultative Forum, the umbrella socio-political organisation for the North, which was founded in the intervening period in 2001. Chief Enahoro met with the leadership of ACF a couple of months later but could not sustain the consultations because he wanted separate positions from the three zones in the North on restructuring, a position the ACF found rather condescending. Since then, a new crop of Northern intellectuals, technocrats and politicians, including office-seekers, have continued the search for a common ground with the rest of Nigeria on restructuring in different ways, but the Northern voice has not really been projected nationally.

The point about the current debate is that the South as a block appears to be for restructuring. This is however more apparent than real. When the questions of how to restructure and the content of restructuring are posed, there are significant differences in the positions in the South, with divergences between the South-West, South-South and South-East. Discussions on the issue in the North might also reveal significant differences between component parts of the North. It is therefore important to reflect on restructuring in a way that will promote both Northern and national unity. This is because the point of departure for the North is that it has more to gain from a united Nigeria, and the restructuring must not be conceived a priori to be against the interest of the North.

Background

We need to introduce some history into the debate on restructuring. Protagonists tend to articulate their positions in a way that suggests Nigeria has not been restructuring. The fact of the matter however is that Nigeria has been restructuring since 1914, when the British amalgamated their three territories in the Nigeria area – the colony of Lagos and the two Protectorates to the North and South of the Niger. This symbolic act representing the “creation of Nigeria” has been widely castigated as an artificial act and a mistake. Such views erroneously believe that there are states that have been “naturally constituted”. We do know however that throughout history, state formations have occurred in a fluid and artificial manner. State cohesion has been built at a later stage. What the British created as Nigeria was made up of many autonomous and independent polities, as well as diverse languages and cultures that were coerced into a new political formation. The problem of Nigeria is not so much the amalgamation of 1914, but the failure to forge a cohesive state from the said territories after independence.

Lord Lugard first structured Nigeria into a political system based on ‘indirect rule’, with a policy of non-centralised administration or separate government for ‘different peoples’. This policy led to the evolution of certain structures and institutions, which to a certain extent still characterise the contemporary Nigerian State. The basic principle of ‘Indirect Rule’ was ‘divide and rule’. In the Emirates of Northern Nigeria and the Yoruba kingdoms of the South-West, indigenous political structures were retained and often reinforced by the colonial administration as the primary level of government, while in the South-East as well as among some of the acephalous ‘Middle Belt’ societies, a new order of colonial chiefs known as ‘warrant chiefs’ was imposed. The system of ‘Indirect Rule’ had a profound impact on the evolution of Nigerian elites.

In the North, the traditional elites were fully involved in the administration of British imperialism, thanks to the system of ‘Native Administration’ (NA) and were therefore allies of the Crown. Secondly, they had a pact with Lord Lugard to keep Christian missionaries and by extension, western education, out of the Emirates. The result was that the pace of development of western education in the Muslim part of the North was very slow and the few who were chosen for the western schools were all employed in the NA. Thus, virtually the totality of the elite in the Muslim North collaborated with colonialism and had a stake in it. In the other parts of the country, Christian missionaries were given full freedom for proselytisation and virtually exclusive control of Western education. It resulted in a fairly rapid evolution of a Western educated elite, to the detriment of traditional ruling elites. The new elite, however, had very limited chances of integrating into the upper echelons of the civil service, even when they had high levels of education. Given their educational background and the frustrations of exclusion, they naturally drifted into political agitation and adversary journalism.

In 1938, the South was restructured into two regions, the West and East, while the North was left intact – hence the origins of the tripartite political system. This system was formalised with the Richards Constitution of 1946. The Nigerian debate over restructuring started with the Richards Constitution. The nationalists – Hubert Macaulay, Nnamdi Azikiwe and Michael Imoudu – rejected the Constitution because it was designed to perpetuate the colonial structure of sharing power between the Crown and Native Authorities and mobilised for a new structure in which citizens would be the repositories of power. They mobilised, travelled round the country, raised funds and went to London in 1946 to demand for a new structure. When five years later, they succeeded on placing self-government on the agenda with Governor Macpherson’s Constitution, the Nigerian political elite had agreed to a federation based on the three tier regional structure Lord Lugard had invented. In the process, the profound demand for democratic government in which power resided with citizens was abandoned. The guiding principle of this “new” tripartite federation was that each region had a ‘majority ethnic group’, which was to play the role of the leading actor – in the North, the Hausa; in the West, the Yoruba; and in the East, the Igbo. In fact, the whole process of constitution making between 1946 and 1959 was an elaborate bargaining pantomime to find equilibrium between the three regions. No wonder the process resulted in the emergence of three major political parties each allied to a majority group.

The pre-independence restructuring was problematic because Nigeria was never composed of three cultural groups but of hundreds of cultural and ethnic groups, dominated by the majority groups. Although Nigeria was profoundly multipolar, the Hausa-Yoruba–Igbo political elites opted to maintain the colonial tripartite structure. It’s important to remember that none of the three regions of the First Republic represented a historic political bloc, as there were minority groups in each. The refusal of the British to create more regions in 1958 when the Willinks Commission affirmed that fears of domination of the ‘minorities’ by the ‘majorities’ were justified, was virtually a disenfranchisement of at least 45 percent of the population.

Post Colonial Restructuring

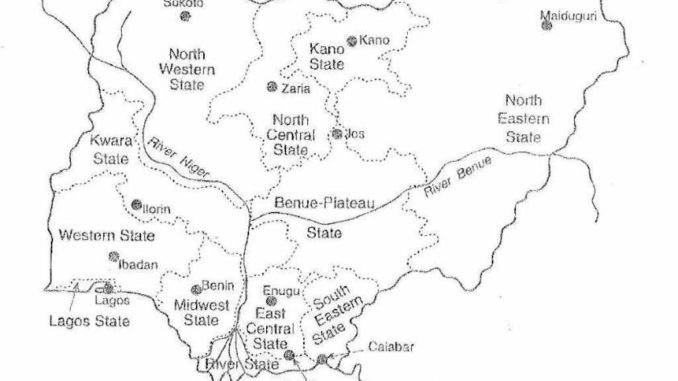

It was the military that subsequently succeeded in completely restructuring the Nigerian State. They dismantled the tripartite structure, which had become quadripartite with the creation of the Mid West in 1963. In 1967, just before the advent of the civil war, the Gowon military administration created 12 states from the four existing regions. The move appeared to have been a political advance because it was addressing the correction of the structural imbalances and ethno-regional inequities of the inherited federal structure. In 1976, the Mohammed-Obasanjo administration increased the number of states from 12 to 19; General Babangida raised the number of states to 21 in 1987 and to 30 in 1991, while the regime of General Abacha increased the number of states in the country to 36.

This restructuring through the multiplication of states has produced a Jacobin effect that strengthened federal power, relative to the powers of the federating states. We should not forget that there was elite consensus that the First Republic collapsed because the regions were too strong. Weakening their power base was therefore the logical objective of restructuring. The real issue however was not the weakening of the states per se, but the erosion of a counter weight to what became known as the “Federal Might”. Rather than correct the ethno-regional balance in the country, the fissiparous state creation tendency by concentrating enormous powers at the centre weakened all political groups that are not in control of the centre. Increasingly, restructuring led to the emergence of a quasi-unitary state. This tendency was reinforced with further restructuring through the decentralisation policy of the Babangida regime, carried out between 1987 and 1991 with the declared aim of increasing the autonomy, democratising, improving the finance and strengthening the political and administrative capacities of local governments. The number of local governments was increased from 301 to 449 in 1989, to 589 in 1991, and to 776 in 1996. Virtually all Nigerians are dissatisfied with the present condition of weak federating units and an excessively strong centre.

Options for Restructuring

(1.) Return to the tripartite regionalism of the First Republic. This is a non-starter as the regions were too large and above all, too uneven. The North alone was much larger than the combined regions in the South;

(2.) Dismantle the state structure and reconstitute Nigeria’s political structure along the six zonal structure. Nigeria is a very large country and the six federating units might be too large to create for citizens a sense of local identity. Some of the zones might also lack internal cohesion;

(3.) Maintain the current 36-state structure but take some power and resources from the federal level and transfer it to the state level. The problem with this option is that the cost of governance has risen excessively under the 36-state structure and the result has been the lack of resources for development. It is this excessive allocation of available resources to maintain the bureaucracy rather than promote development that is largely responsible for the current crisis in the country;

(4.) A return to the 12-state structure of 1967 is the best option open to Nigeria at this time.

Return to the 12-State Structure

The distortion of the 12-state structure by multiplying the number of states was done to appease new minority groups that emerged after state creation, to spread federal largesse more evenly and sometimes for selfish reasons. Today, Nigeria cannot sustain the 36-state structure due to their over-dependence on oil revenues that would continue to dwindle in the coming years. The key principle for restructuring are as follows:

(A.) Have states that are economically viable and can rely on fiscal resources they generate themselves;

(B.) Ensure that States operate in a democratic manner and are run by governors that are accountable to the people and legislators that are not subservient to tin gods;

(C.) Give states the constitutional and legislative powers to determine their internal structures such as the number of local governments.

(D.) Address the fear of domination by a combined implementation of the power rotation and federal character principles at all levels, which recognises and combines both merit and the need for fair representation of the broad identities that make up the federation and states – specifically, geography, ethnicity and religion;

(E.) Balance the desire for local resource control and the viability of the federation as a whole.

Constitutional Proposals

i. A return to the 12-state federal structure of 1967. The 12-states would be the federating units of the country;

ii. States shall have full control of their resources and pay appropriate taxes to the federal government;

iii. States shall have the powers to create and maintain local governments as they desire;

iv. Overhaul the Legislative Lists and reassign agriculture, education and health to the Residual List in which states alone would have competence but the federal government would share a regulatory role with the States;

v. Mining should be reassigned to the concurrent list with on-land mining under the federating units and off-land mining under the control of the government of the federation;

vi. The power of taxation should remain concurrent;

vii. The Federal Character principle should be retained and strictly and universally observed;

viii. The Senate should be abolished and we should have a unicameral legislature.

Bashir Othman Tofa

Fatimah Balla

Sule Yahaya Hamma

Abubakar Siddique Mohammed

Sam Nda-Isiaih

Bashir Yusuf Ibrahim

Bilya Bala

Aliyu Modibbo

Usman Bugaje

Hubert Shaiyen

Kabir Az-Zubair

Jibrin Ibrahim

Be the first to comment