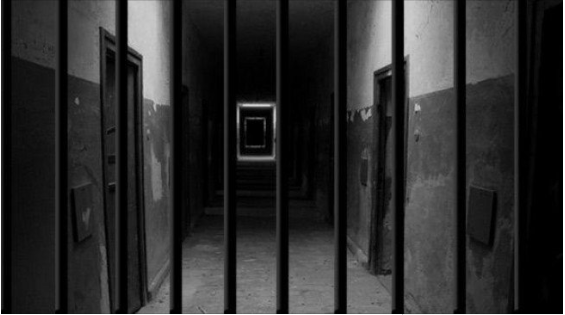

NIGERIA’s prisons are in dire straits. Congestion, lack of health care, access to legal representation and shortage of personnel are inexorably their sordid features. One of these shortcomings – congestion arising from the high number of inmates on death row – has moved the Attorney-General of the Federation and Minister of Justice, Abubakar Malami, to lament.

A total of 1,832 inmates have been waiting for the hangman’s noose for a long time due to the failure of state governors to sign death warrants, which they are officially obligated. Moral, religious and political suasions appear to be obvious rampart. Malami says the ministry “is presently preparing a memorandum to the National Economic Council to apprise the governors of this issue and seek their cooperation in addressing this challenge.”

This is not the first time the issue would engage their attention. In February 2017, the Vice-President, Yemi Osinbajo, called on the governors to discharge this constitutional obligation at a NEC meeting, which he presided over. He got firm assurances, but they were observed in the breach. Adams Oshiomhole, as the then Edo State governor, is the only one that has risen to the challenge since 1999. In 2012, he signed the death warrants of two convicts, reviewed the cases of four others: two of them were set free, while the other two had their death sentences commuted to life imprisonment.

The Oshiomhole example recommends itself to governors. Doing so will help in decongesting the prisons. However, it is irreconcilable that governors who dither over the signing of death warrants are at the same time recommending capital punishment as an antidote to kidnapping in their states. Virtually all the states in the Southern part of the country have enacted this stringent law.

Governor Nyesom Wike, for instance, in signing the Rivers State Neighbourhood Safety bill into law in March this year, forcefully conveyed the message: “If you are convicted of kidnapping and the Supreme Court affirms your conviction, I will sign the death warrant without looking back.” His counterpart in Lagos State, Akinwunmi Ambode, avowed similarly. While initialling the anti-kidnapping legal instrument, he said, “We are confident that this law will serve as a deterrent to anybody who may desire to engage in this wicked act within the boundaries of Lagos.” In Abuja, the National Assembly toed the same line when the Senate enacted capital punishment for kidnappers in September last year.

Sending condemned criminals to the gallows is a controversial human rights issue globally, which legions of rights crusaders oppose. A total of 106 countries have no capital punishment. Among them are Germany, France, Italy, South Africa, Senegal, Burundi, Angola and Guinea. Nevertheless, some states in the United States like New York, California, Florida, Tennesse, Kentucky, Utah and Washington, still uphold the death sentence by hanging, gas inhalation and firing squad.

Decongesting Nigeria’s 239 prisons is a critical challenge the governors should embrace by either signing the death warrants or commuting death sentences to life imprisonment, in line with the dictates of the law. This will put a closure to the psychological, moral and financial burden the situation inflicts on the convicts and their families, on the one hand, and the state, on the other. Under a true federal arrangement, the management of prisons is under the purview of both the central and state governments. This recognition explains why it was one of the items in the Exclusive Legislative List that the 2014 political conference delisted in its recommendation on devolution of power. Nigeria’s prisons had inmates’ population of 73,631 as of July 16, 2018, comprising 72,156 males and 1,475 females. Out of this number, 23,472 persons are convicts, while 50,159 prisoners are awaiting trial.

Prison congestion subjects inmates to inhuman conditions like hunger, disease and filthy environment, which quite often provoke them into rebellion. In 2014, the Koton-Karfe Prison in Kogi State recorded a jail break, which 145 inmates took advantage of to flee; in 2009 a similar incident occurred and bandits released 199 inmates awaiting trial. Between 2009 and 2014, a total of 2,255 inmates had escaped during these security breaches, according to the prison authorities.

The Minister of Interior Abdulrahman Dambazzau’s observation, when he made an unscheduled visit to the Port Harcourt Prison in January, is instructive: “I can tell you that anyone who goes to that prison will come out as an animal.” The 100-year-old facility, originally designed for 800 prisoners, now accommodates 5,000 inmates.

However, prisons in well organised societies serve as reformist or correction centres, rather than punitive places. International protocols such as the Geneva Convention, UN Convention against Torture and International Convention on Civil and Political Rights that forbid any form of brutality or indignities against convicts, are enforced. The newest jail in Britain – HMP Berwyn, located in Wrexham, with the capacity to house 2,100 prisoners – epitomises this paradigm. An inmate there is kept in a two-man room with a laptop, phone, shower and a toilet to boot. But a prison cell in Nigeria animalises, according to Dambazzau.

The 36 states governors, therefore, should take the bull by the horns.

END

Be the first to comment