No historical sketch about the struggle against imperialism in Nigeria will ever be complete without a mention of the impact of the Zikist Movement; a radical revolutionary youth body which was founded 70 years ago on February 16, 1946 (to be precise) by young enthusiastic multi-ethnic Nigerian nationalists. Among its founding members were Kolawole Balogun who became the first President, M.C.K. Ajuluchukwu who became the first Secretary General, Abiodun Aloba, Nduka Eze, G. Onyeagbula, M. Aina, G. Ebo, J. Inoma and S. Aderibigbe to mention but a few. In the 1940s, the youths were unsure about the pace and commitment of the elders to immediate self-government.

This period was also an era of self-determination and educational expansion. World War II and its immediate aftermath ushered in a worldwide depression and this in turn ignited the demand for self-governance. Some notable changes that began to take root before the downturn of this era included urbanisation, western education and transport. All this contributed to the growth of nationalist activities. Newspapers, magazines and information began to circulate and this influenced opinions. Political and nationalist ideas also grew and proliferated within cities. The spread of western education especially in the south created a population segment that could read and write, producing leaders with new ideas, visions and ambitions. A growing local media allocated space for anti-colonial issues and political associations emerged and quickly became key nationalist platforms. The General Workers’ Strike of 1945, the formation of the Zikist Movement in 1946 and the Burutu Strike of 1947 were all key catalysts of change that fuelled and intensified this national clamour for self-governance although from a political view point, the formation of the Zikist Movement was arguably the most significant of these historical occurrences.

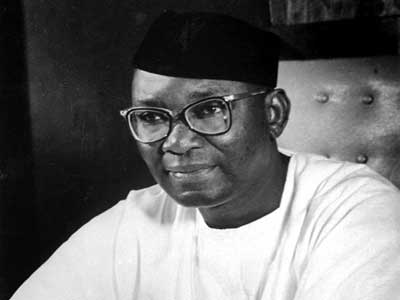

The leaning of the Zikist Movement was socialist and anti-colonial in outlook and in its early years, acted more or less as the youth wing of the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons. The Movement pledged positive action in defending Nnamdi Azikiwe against attacks by his opponents and to further take on the repressive nature of colonial rule by seeking its end. The Movement garnered some of its inspiration from the writings of Nwafor Orizu in his book, “Without Bitterness”, and from Nnamdi Azikiwe’s own book, “Renascent Africa”. Orizu has been credited with coining the term “Zikism”, a vague expression that he described as not being racialism, jingoism, anarchism, monistic or sarcastic but a form of social life that strives to redeem Africa from social wreckage, political servitude and economic impotency. The aims and objectives of the Zikist Movement were among others as follows:

- Zikism holds that self-determination constitutes the inalienable right of the people, and that colonialism is wholly incompatible with this right.

- Zikism accepts the Marxist thesis that the economic factor conditions the moral, legal and political aspect of development in any society and therefore urges the need for a just distribution of national wealth.

The Movement’s height in popularity was between 1948 and 1949 at a time self-determination movements had just propelled India to Independence in 1947 and a riot in Ghana had resulted in some political concessions being granted to the nationalists over there. By the beginning of 1947, the Zikist Movement had 29 branches all over Nigeria and was attracting dedicated young people who were willing to sacrifice their careers for a righteous political cause. Notable among such people were Raji Abdallah and Adesanya Idowu.

By 1948, preparatory measures were in full swing for the recruitment of youths and other interested members into this active anti-colonial group. The movement began to intensify its attacks on colonialism and ensured that their ideas became more potent and remained in public consciousness by making use of strikes and boycotts, as well as other propaganda through lectures, publishing of newsletters and revolutionary pamphlets. A particularly revered newsletter was written by Osita Agwuna called “A call to Revolution”. It was earlier delivered as a lecture by Agwuna under the chairmanship of Anthony Enahoro and called for positive action which included:

(b) Boycott of schools and employment (including the Police and the Army).

(c) Non-payment of taxes to Government but instead to the NCNC and other nationalist organisations.

(d) Mass violation of every law and executive order that negates human rights.

(e) The flooding of the prisons with protesters in the mode of India under Ghandi.

(f) The programme of non-cooperation with the authorities and civil disobedience as a means of liquidating imperialism in Nigeria.

In a call for revolution, the movement also asked for direct participation from Nigerian school proprietors who had suffered from grants-in-aid and asked that they inculcate contempt for the British authorities amongst their pupils. It also encouraged students abroad to take courses in military science and called for young people to join in ending tyranny through militant tactics. The movement not only directed their frustration against British interests and persons but also African nationalists and organisations that were viewed as stooges of imperial interests. For this type of public call and similar activities, some Zikists were arrested and tried. The trial came to an end on February 2, 1949. The five men who were sentenced to various terms of imprisonment were Enahoro, Agwuna, Abdallah, Oged Macaulay and Smart Ebbi. Finally, on April 12, 1950, the Zikist Movement was banned.

Although as already outlined, the Zikists’ agitations were directed against two main quarters, namely the British colonial administration and agents of British colonial rule in whatever form, it did not appear that their extremist stance had the blessing off the NCNC or its leadership. Zik in his INSIDE STUFF column in the West African Pilot had described them as “fissiparous lieutenants and cantankerous followers”. In a presidential address at the Annual Convention of the NCNC in Lagos on April 4, 1949, Zik, in an obvious reference to the Zikists, said:

“We must inculcate a sense of discipline and responsibility in our cadre. An unprincipled and irresponsible army is a liability, and not an asset, to any nation; individuals must realise that membership of a national movement is neither a permit for licentiousness nor a warrant for irresponsibility. Lastly, the rank and file of our national movement must rely on the leadership to develop its own techniques, strategy, tactics and logistics. This requires implicit obedience, loyalty and tact. A disobedient, disloyal and tactless followership is just as suicidal to the national cause as an unprincipled and cowardly leadership. When the followership becomes impatient of its leadership, the course to follow is not to lose faith and become confounded, sullen and disillusioned, rather it must trust those at the helm of the ship of state, remembering that ‘true courage is always mixed with circumspection’, this being the quality that distinguished the courage of the wise from the harshness of the rash and foolish…”

PUNCH

END

Be the first to comment