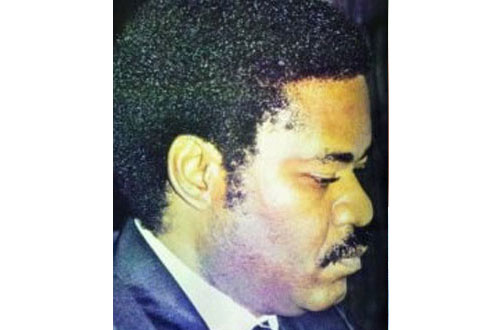

This man who liked to brag about his intellectual power, who loved to say that he was the best journalist in Nigeria, never suffered any fool gladly. He did not glide gently through the world. By the time he was letter-bombed at 39, a truly unique morbid incident in Nigeria at that time, he was just beginning to realise some of his tall dreams.

Since Dele Giwa was killed by a letter bomb on October 19, 1986, every anniversary of his death has remained for me a moment of sobering reflection on the precarious nature and power of journalism. It has also remained for me a time to re-read Giwa’s essays, remembering the indebtedness of many members of my generation to his own inspiring spirit of journalistic enterprise. Frequently, old writings in journalism fade or lose their effect. But Giwa’s wonderful writings, after several seasons of rereading, have not lost their shine, their wit, punches and astonishment. They still repay attention. As one of the pioneers of modern Nigerian journalism and one of its exemplary practitioners, Giwa raised the bar of investigative journalism as the features editor of Daily Times, as the editor of Sunday Concord and as the editor-in-chief of Newswatch magazine. He died a hero’s death and his legacies of a good name and enchanting words will not be obliterated.

The lesson of his honour and glory must not be lost on many of our journalists and public commentators who behave like desperate and hungry scavengers rummaging through the heaps of our national vices. Among our country’s media owners and newspapers editors, rank greed has set in. How do you hope to call robbers in powers to proper accounting if you are a beneficiary of their loot? Many of our watchdogs that used to bark at the wounds of the country now lap up the pus of its open sore. It is diminishing, to say the least, that the public that used to venerate many hard-working journalists simply dismisses the majority of them today as frauds, unprincipled self-servers and double-dippers. Do we, or do we not, pass over in silence what we should rail against? Has the press freedom guaranteed by our constitution and Freedom of Information Law not become, to some journalists, licence to scandalise and blackmail the innocent? Yet, to quote what Harold Evans, former Sunday Times of London editor and author of Good Times, Hard Times and, recently, My Paper Chase, said in India on November 15, 2007: “We cannot justify freedom of the press by assertion but only by day-to-day demonstration of integrity. It is our principal defence in sustaining public support.” In other words, journalism will die when the public no longer trusts it – when it lacks integrity.

Dele Giwa, who was initially very uncritical and naïve in the way he related to Presidents Shehu Shagari and Ibrahim Badamosi Babangida, later became committed to making sure that they and others who were in positions of authority were challenged to account for their deeds. He never liked to be the errand boy of some powerful elements: he enjoyed it when he dominated his environment as a journalist. He once wrote in one of his rejoinders: “I have said at every available opportunity that NOBODY tells me what to write in my column. It is my property, and I guard it jealously, for it is my freedom to think and write as I see. Nobody higher than me in the Concord Group has ever demanded my column for editing before publication. Any reaction to any of my columns has come after publication.” Giwa wrote two columns for the Daily Times between April and November 1979; a column in the Sunday Concord between 1980 and 1985; and wrote for Newswatch between 1985 and 1986. He did all that in addition to his job as an editor and his obligations as a manager. It is formidably instructive that many years after his tragic demise, we are still grappling with many of the problems he wrote about.

What did journalism mean to him? How should a journalist interpret his world? What should a journalist’s camera see? To put the question another way: what did he consider as the responsibility of the journalist? He explained in a piece in his Press Snaps column titled “The Problem of living by the Pen” on May 23, 1979: “All a journalist is supposed to do is to go out to collect materials for stories that he must write in clean, clear and simple prose.” He wrote further in another piece, using Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, the two wonderful Washington Post reporters who broke the Watergate scandal as examples, that the reporter should go out and get information that other papers don’t have. “That’s what journalism should be. Information is not simply public relations garbage, but it is something new and newsworthy.” Giwa was after deep answers. In the hot exchanges between him and Areoye Oyebola and Andy Akporugo, he later added ‘courage’ and ‘decency’ as virtues that a good journalist should posses. Writing in Sunday Concord of November 22, 1981 under the caption, “Mr. Oyebola’s blah and other blahs,” he observed that “courage is the one crucial element lacking in the Nigerian press. And just as Nigerians like to knock Nigeria for everything wrong with them, as though they don’t constitute Nigeria, those Nigerians who call themselves journalists like to knock the press for lack of courage, as though they don’t constitute the press.”

It was a response to Alade Odunewu, Magaji Dambatta, Lateef Jakande, then Governor of Lagos, and Oyebola, who had criticised the press that November, for lack of courage. Giwa felt that while Jakande had the moral right to accuse some journalists of cowardice, Oyebola did not have that right because he was not at his post as courageous editor ought to be the day General Yakubu Gowon was overthrown. Giwa believed that Oyebola was removed as editor of the Daily Times by Babatunde Jose because of that. He then wrote that “Journalists are not 9-5 men and women. A journalist is perpetually on call. A good one wherever he is when an important story breaks, he will head for his desk and his typewriter. An editor, if he’s abroad when something as big as a coup breaks must fly back home to take charge.” This was not a personal beef with Oyebola. Of course, Oyebola, the brilliant author of Black Man’s Dilemma, replied him in equal measure, saying that he had demonstrated courage in the past in his Frank Talk with Omo Oye column and that his removal as the editor was as a result of some pettiness.

Giwa did not agree. He was determined to hold on to his point as he wrote back tersely in a footnote: “The point really is that Mr. Oyebola failed in his rejoinder to address himself to the crux of my column on him. Where was he on the day that Gowon was overthrown? Why did he stay home on the one day that he had the chance to show that he was a man of courage in all its ramifications? Where was he? Let him tell us, for it was the one point that he failed to mention in his well-written and well-annotated rejoinder.” He felt that Chris Okolie, the publisher of New Breed magazine, was courageous and he celebrated him: he also felt that the young Peter Enahoro was brave, and wrote a three-part series in Daily Times of December 1979 in praise of him. To all journalists, then, his urgent appeals were: You should have a passion for the job. Be brave but don’t be reckless. Don’t allow them to beat you into silence. Cry out questioningly. Try and rise above trivial pursuits. Give your country quality journalism.

Dele Giwa regarded himself as a modern journalist. He did not have any patience with the half literate, foul smelling old journalist who could not get his sentences right, wore shabby clothes and dirty shoes, and went from court room to court room to pick up the proverbial ‘brown envelopes’ to augment his sorry income. He could not stand the old journalist who felt threatened by the brash, headstrong, exuberant and confident new one who had just arrived on the scene. He saw himself as representing the younger, urbane and extremely well-educated journalists, “able to hold their own against the most arrogant newsmakers who regarded journalists as boys who never grew up.” Arguably, Giwa’s arrival on the terrain, along with other journalists like him, announced the emergence of a new style, a paradigm shift, a change in the journalist’s perception and presentation of reality. Irrefutably, as a modern journalist in a developing world, he believed it was his duty to satisfy all those who asked for more information, not just information in the sense of the man biting the dog, but more explication of the information being handed out.

He called for people better trained, people with the sort of minds to sift information, to pick the useful and discard the useless and find the lie carefully tucked into masses of details. “The modern journalist”, he wrote, “is required to know a little about many things, more than a little. In fact, enough to make sense of most issue such that he doesn’t appear stupid. He is invariably a university graduate, a good thinker and a man with a way with words. But he is not a philanthropist. He does whatever he does to make money, for he has chosen a career in which he wants to spend his life, in which he wants newsmakers to respect him. He wants to dress well and he wants to live in a good house and drive a nice car. This calls for money. And so, increasingly, he asks for more money and more perquisites. He also wants a good office and he likes to read his articles well printed on good papers from a good rotary machine. Money. Money. So when a newspaper says it wants to increase its cover price and increase its advertisement charges, it is doing so to be able to make journalism a worthwhile endeavour, to make it possible for journalism to provide adequate coverage of the many intricate issues of today.”

To read Giwa’s gutsy pieces, especially those on the innocence and potential of youth, freedom of speech, the practice of democracy in our country, the selfishness and greed of members of our National Assembly, the high rate of unemployment, the curse of oil…is to be confronted by the bluntness and the timelessness of a gifted writer’s truth.

In June 1979, Dele Giwa noticed that journalists were not covering political campaigns well, and wrote a piece in his Press Snaps column telling them what to do. He opened by reminding journalists of the beautiful things that Esbee and Cee Kay, sports columnists for Daily Times, did in those good old days when they were reporting sports. Now his points on unbiased political reporting:

Apart from providing excellent literary entertainment, the stories of the two columnists provided for their readers the best analyses of the game plans of the opposing teams. In journalism what Esbee and Cee Kay did is called analysis of strategy in a game of chance. And if that can be done in sports writing, most certainly it can be done in political reporting. Indeed it is called for because politics is the biggest game of chance. Of course, in writing political analysis for the newspaper the reporter will not have the licence to take sides with any of the contestants. He will be expected to be an impartial as humanly possible in analysing, say, the political and campaign strategies of the candidates in a political race. In other words, a reporter covering a particular candidate should be able to give readers details of the candidate’s plan and method for winning the voters to his side.

He will write for his understanding of the candidate, having spent time following him on the hustings and having digested every one of his speeches and position papers of his party. The reporter will be expected to understand the candidate’s issue and see whether they are pertinent to the needs of the nation. And then, he must watch carefully how the candidate presents his issues to different segments of the electorate. Are the candidate’s promises outlandish? Does the country have the resources to fulfil the promises? The reporter must ask these questions in his stories and find answers to them by talking to experts in fields concerning each issues and promises and then probe the electorate’s reaction to them… The truth is that Nigerian newspapers have failed to ask these pertinent questions. And without asking them and finding answers from all the segments of the nation, the political correspondents cannot claim to have given their readers complete pictures of the political scenes. Journalism has gone past the stage in which all a reporter does is to report what a man says. Yes, doing that is basic to his calling, but he must then take what the candidates are saying to critical and objective analysis. It’s not too late to start talking about the drive behind the candidates, that they have not been debating issues and that they are talking over each other’s heads down to the electorate. Voters in this country would still like to know the weaknesses and strengths of candidates, their resilience and temperament and the character of their advisers. We have heard all the promises but are the candidates disingenuous in making some of them? The political reports must tell us.

That was Giwa, the interpreter of journalism rules. As an editor, he enforced some of the rules. By the time Giwa turned 34, he had become one of the country’s most colourful and most literate journalists. Kole Omotoso, the novelist, was on his way to the Goethe Institute in Lagos to give a reading from his books, and visited Giwa in his office. And as he was leaving, Omotoso joked that he was a writer but Giwa was not. In pursuit of knowledge, driven by curiosity, and a spirited urge to prove his worth, Giwa did not take it as a joke. He went out and bought all the books that Omotoso had put out. “I read them all,” he later wrote, “and at the end, I couldn’t grasp Kole’s meaning of seeing himself as a writer and saying that I wasn’t.” He argued persuasively, quoting Tom Wolfe’s New Journalism as his authority, that “the most important literature being written today is in nonfiction, in the form that has been tagged, however ungracefully, the New Journalism…” He loved every excellent novelised news report.

To him the question for a serious minded journalist should be: How much of a journalist am I? He proved that he was a damn good one: his reporting was powerful. His editing was skillful and his prose was eloquent. He practised the profession in a way that made people fall in love with it, in a way that made people respect it, in a way that made literate readers appreciate its tone and significance. He embodied the ideals of the editor as mentor, the manager as humanist and the journalist as opinion-moulder. He argued passionately for journalistic principles and suffered for them. Indeed, in 1982, the then Inspector General of Police, Sunday Adewusi, ordered the arrest and detention of Dele Giwa in one of the cells at the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), Alagbon Close, for publishing in the Sunday Concord the government white paper on the report of a commission of inquiry that investigated the fire outbreak that destroyed the Republic Building in Lagos. His friend Ray Ekpu was also detained for predicting in an opinion piece that the arsonists who torched the Republic Building might choose the headquarters of the Nigerian External Telecommunication in Lagos as their next target, which they actually did the following day! Ekpu was promptly charged with murder, arson and conspiracy. The case, expectedly, increased Giwa’s popularity rating and enhanced his glamour appeal: it was one of Dele Giwa’s Camelot moments. The other was when he left Sunday Concord to co-found Newswatch with Dan Agbese, Yakubu Mohammed and Ray Ekpu.

To read Giwa’s gutsy pieces, especially those on the innocence and potential of youth, freedom of speech, the practice of democracy in our country, the selfishness and greed of members of our National Assembly, the high rate of unemployment, the curse of oil, the poor state of our infrastructure, the need for a regime of meritocracy, the call for public service reform, the terrible image of our country abroad, the failure of Nigerians to believe in their country, the need for courage and solidarity among journalists and the escalating waves of crime in Nigeria, is to be confronted by the bluntness and the timelessness of a gifted writer’s truth. He was generally light, breezy and chatty. Even a casual reader would not fail to notice the felicity of his prose and their exact revelation. He was not a poet but he sometimes wrote in the cadences of a poet. He was not a playwright yet he sometimes made the best use of the language of drama in his columns. As a buff of popular literature, a lover of music and a film enthusiast, he occasionally adorned his essays with moving lines from songs, novels and films. He admired creative artists like Ken Follet, James Clavell, John Le Carre, Graham Greene, Ernest Hemingway, Tom Wolfe, Truman Capote, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Norman Mailer, George Orwell, George Benson, John Denver, Bob Dylan, Stevie Wonder (he even named Aisha, his daughter, after Wonder’s daughter) and several others, because they inspired him at one time or another. Giwa paid close attention to the literary quality of his journalism. And he was well respected by his colleagues for it. He trained his eyes on the foibles of his society and persuaded his readers to rise above them. It was as if he was inevitably asking us to employ his own seductive hopes and powerful social imagination to illuminate our grim conditions.

He kept hammering on the need to commit seppuku, the need to love the country much more than ourselves because without it, he reasoned, the country would be destroyed by its greedy, selfish and arrogant rulers. Exactly six years before he was murdered in his library in Lagos, Giwa had written a piece…in which he criticised the corruption…of our National Assembly members.

How does a writer reach for excellence? How does he commit himself to reasoned courage? These questions lubricated Dele Giwa’s path as a columnist. His first Preface to Cover in Newswatch titled “Guts, the Right Stuff” on Wole Soyinka, one year before Soyinka won the Nobel Prize in Literature and one year before Giwa was cut down gruesomely, attempted to answer that question. Soyinka, he said, “is not keeping quiet. He is forever squealing, squealing like Gunter Grass in Germany, another artist who hates tyranny in all its colours. He is squealing like Jacobo Timmerman, the Argentine Journalist who writes in blood his experience in jail for squealing on tyranny… Enough Soyinkas from Maiduguri to Calabar and from Lagos to Sokoto may set us free of the leeches eating at the soul of Nigeria.” To him, a writer is ‘the right stuff’ if he has a sense of outrage against injustice. He wasn’t satisfied that “not enough Nigerians have the guts to get angry and squeal.” Yet he strongly believed that “Nigeria needs squealers, those who are prepared to commit seppuku (Japanese for suicide) for the father land.”

Obviously, it was not just from writers that he expected this virtue; he felt that it was something that every responsible citizen should possess. In the Sunday Concord of August 2, 1981, he argued most coherently about a sense of patriotism that was lacking in many Nigerians. And with a sense of outrage he lamented our history of perfidy and subservience:

When the European came to Nigeria and the rest of Africa, the black man sold out to him, capturing some of their own and selling them to the white man for pittances. That’s when the black man lost the fight. At the same time that the Japanese was exploiting the white man’s “barbaric curiosity.”

Nigeria and the rest of Africa were busy selling out, getting nothing in return. Today, that sell-out is the reason for Africa being referred to derisively as under developed. Nigeria, for one, has a chance to get up and go, if for nothing else but for its oil wealth, but something that can be called a lack of national will is tying down the nation. This has nothing to do with the government, as much as it has everything to do with the Nigerian who doesn’t seem to believe in his fatherland, who seems too ready to make a quick buck at the expense of the nation… if only the Nigerian – whatever his or her station – will think less of himself and think more about the nation, maybe then Nigerian will begin that tough march into the future. The question, really, is: How many Nigerians are willing to commit seppuku for Nigeria?

He kept hammering on the need to commit seppuku, the need to love the country much more than ourselves because without it, he reasoned, the country would be destroyed by its greedy, selfish and arrogant rulers. Exactly six years before he was murdered in his library in Lagos, Giwa had written a piece titled “Modest Proposal” in which he criticised the corruption, the waste of resources and selfishness of our National Assembly members. He might well be talking about the current members of the Assembly:

Why are these fellows wasting the tax payer’s money gallivanting around the world? It constitutes an incredible joke to see a Nigerian legislative committee on internal matters going to the United States. To do what? Nobody suggested that democracy would come cheap. Even if the system were designed for its money-saving possibilities, the sets of legislators elected in 1979 saw their elections as means to live like rubber barons. Since coming to Lagos, the National Assembly members have displayed such selfishness that their only legislative achievements were in fighting for higher salaries for themselves, and trying to empty the national treasury by voting dizzying amounts for themselves as allowances. Because the president and governors who constitute the national executive council said that the legislators couldn’t make the nation poor in their efforts to make themselves rich, the legislators embarked on a single-minded exercise to amend the constitution…

All that pales in comparison to the lawmakers’ penchant for overseas travelling which brings about the modest proposal. Members of the National Assembly should introduce a bill proposing the transfer of the assembly to either New York or London where they could all live and from where they could be visiting Nigeria. The American Government may not object to the proposal since that would give it the chance to watch the lawmakers and educate them on the presidential system. Or, in the extreme, to ban any legislator from embarking on a foreign visit at the expense of the tax payer for at least one year.

As a sophisticated liberal humanist, Giwa wrote in a moving manner about the unfortunate army of unemployed graduates in Nigeria. As an employer of labour himself (Chief Executive Officer of Newswatch) he lamented the heap of application letters in his office. That was when General Ibrahim Babangida placed an embargo on employment – a policy dictated by the International Monetary Fund. In writing about applications for employment which “have taken on a note of entreaty for survival,” he blamed Professor Emmanuel Edozien, who was once a Minister of Economic Planning under Alhaji Shehu Shagari. How could a genuine professor of Economics have refused to heed Chief Obafemi Awolowo’s timely warning in 1980 that Nigeria’s economy was heading for the rocks? Giwa wondered. He believed that if the economy had been carefully managed, there would have been jobs for many people. But he did not stop at that. He also blamed Nigerians for their laziness. His words: “Nigerians, let’s face it, like easy answers and easy money. Nobody really wants to work hard. Now that the oil is drying up, and that’s the truth, many people are afraid of hard work that must follow if this country is to find a way. And in the middle of indecision, people are suffering: The hard days are here, and nobody knows what to do. People are feeling sorry for themselves, for most people have forgotten the meaning of hard work.”

In May 1985, when Nigerian journalists celebrated thirty years of the founding of their union, Chief Chike Ofodile, the Minister of Justice in the Buhari/Idiagbon era was invited to talk on Decree 4 and press freedom. Ofodile spoke in support of the decree. In a rather bitter reaction, Giwa stood Ofodile’s logic on its head. He said Ofodile’s position was very dangerous. He asked: “How does Ofodile expect the press to assist the government in enforcing accountability if the press lost its right to protect the sources of information?” In its arrogance of power, the Muhammadu Buhari/Tunde Idiagbon regime inflicted on Nigerian journalists the decree that forbade frank thought and unvarnished reports.

In a piece he wrote on armed robbery in Nigeria, Giwa suggested that the police were losing out mainly because they were not as sophisticated as the robbers:

The robbers know how the police operate, but the police don’t know how robbers operate. They know too well that the police are immobile. They man roadblocks and check vehicles and the occupants in much the same way all over the city. If you are stopped and you put on your inner light and wind down your window before you are asked, and you grin at the police they will ask you to open your boot. And that’s it. No effort is made to look at you if you have any bulge under your jacket or your buba. And nobody looks in the glove compartment of your car or takes a peek under your seat where a weapon could be concealed. And of course the roadblocks are in specified positions. Even if they are moved around, the robbers will survey their areas of operations before setting out. And they thus know the routes that are free. That is why they win and the police lose.

The situation remains essentially the same. If Giwa were still alive he would have observed a more citizen-friendly police officer at the checkpoint who stops you and asks, “How is your family, sir!” And if he sees a press sticker on your car, he would say excitedly, “Ah, press! I bow and tremble, sir! Your boys are on duty! Just anything to buy pure water, sir!” Yes, our police are not well paid, they live largely in slums, they lack the sophisticated equipment to combat modern day armed robbers, but they also lack the decency and moral courage to wage a ruthless war against those robbers with whom they sometimes sit in secret to share the loot.

There must be something abnormal about a people who troop out to dance for a governor who has been proved by a legally constituted authority to be a looter of the state’s treasury. Giwa once observed that Nigerians behave that way because “they have been shocked to the state of unshockability.”

Giwa had his own encounter with armed robbers when they snatched his Honda Prelude in April 1982. The car was less than two weeks old when the carjackers robbed him of it. His reporting of it is a true measure of his gift:

The mallams had just finished sweeping the front yard of the house and were getting ready to open their kiosk for the day’s business. The horn was saying that the gate should be opened and that one fateful minute of waiting while the hook was moved and the gate opened. In that one minute, I looked up into my rear view mirror, lest another car was held up trying to drive past. Then I saw it, a metallic brown Peugeot 504 SR car with three rather gentle looking young men inside. No panic. Earl Klugh was still playing, but a little sense of discomfort touched me as I thought the opening of the gate was holding up the gentlemen who were perhaps waiting to drive past and go their way.

I saw that the plate number read something like OG- something -JA, and I knew that they could not have been my friends, and so could not have come to visit me. For the car did not drive past as I turned into my driveway and the mallams were opening the garage for me to drive in. They followed me, bumper to bumper. Even then, I sensed no danger. After all, the Prelude was mine; I bought it with my hand and salty sweat. Before I could turn off the engine, two occupants of the car materialised at the window on the passenger side of the car.

I frowned, and the next thing I saw were two narrow nozzles of hand guns. One was aluminum in colour, and the other was black like an ugly snake. The first split of the close encounter brought a rush of confusing emotions; anger, humiliation and a sense of loss; but no fear. “Your hands up, and get out,” that was from the guy with the aluminum gun, the type called Saturday Night Special in the United States. The guy was well dressed, a gold chain dangling from his neck, but his face was contorted with a nervousness that dilated his pupils. His friend, the other one with black gun, was silent and he was the one that told me with his menacing visage to listen to the clean-cut fellow with the aluminum gun. “Out and keep up your hands, or I will kill you.”

It’s a kind of gentlemen’s agreement and I knew that if I failed to make a choice, get out and keep up my hands, then he was free to kill me.

So, I obeyed. He got in that beautiful white lady. But he had a problem. The car was automatic, meaning it had no clutch and that you couldn’t move the car from Park to Reverse or Drive without pressing a small button on the shift to move the car.

These guys, no matter how long they have been at it, stealing people’s cars and threatening death if the hands didn’t go up, had never stolen an automatic shift car and didn’t know what to do. I was looking at him as he struggled with the gear, and a wave of perverse relief ran through me. “Show me the reverse,” the man with the aluminum gun yields. I was happy and I began to move fast into my residence, even as I sensed that the third man in the getaway 504 covered me with a heavier and more sinister-looking automatic gun. “Shoot, damn it,” a silent sound said within me. But sadly, the car suddenly jumped back and the get-away car screeched back and they all drove away like phantoms, with my beautiful white Prelude. LA 6343 KE, like an eagle, flying after the 504.

That recalls the one he had written earlier in Sunday Concord of November 2, 1980 in which he observed, among other things: “Ten years ago threatening letters from armed robbers challenging whole neighbourhoods to a duel would have made screaming headlines on the front pages of most newspapers, unlike nowadays when they are virtually ignored by the media in that they have become too commonplace to be regarded as news.” Many of the robbers have since become kidnappers, oil robbers and mercenaries for Boko Haram and ISIS. Worse still, some of them have moved to law courts and churches to continue the robbery spree.

The May 1986 riot at Ahmadu Bello University (ABU) Zaria, in which some innocent students were killed by the police, presented an occasion for Giwa to indict the government, to attack the police and to dismiss the then Minister of Education, Jibril Aminu, as an architect of violence against reason, an enemy of students and lecturers, the bigot of a special kind, a man who was determined to destroy the Nigerian university system. The then Vice-Chancellor of ABU, Ango Abdullahi, too did not escape his barbs. He believed that the future of Nigeria belong to its youth: “Children such as most of the kids in our universities are like spring itself, the prime of life that must be tended like a beautiful flower in bloom. They represent the future of the fatherland, the segment of the population in whom the government and the people plant their hopes for the future.” Giwa must be sad in his grave that many Nigerian students in our public universities are learning under what Jean-Paul Satre, the brilliant French philosopher and literary theorist has called a ‘nervous condition.’

How come the vile and corrupt walk our streets as heroes and heroines? Why don’t we teach them a hard lesson or two? Instead, we are amused, while some even protest on behalf of the rogues. There must be something abnormal about a people who troop out to dance for a governor who has been proved by a legally constituted authority to be a looter of the state’s treasury. Giwa once observed that Nigerians behave that way because “they have been shocked to the state of unshockability.” Also, he said that Nigerians “regard themselves as passing sojourners on the geographical amalgam called Nigeria. It is like standing away at a distance and looking like riveted spectators at the greatest inferno in the world. Nigeria is on fire and the citizens are amused.” Pause for a moment to consider the metaphor of a people who stand akimbo and laugh while their only house is on fire. People who do that need urgent psychiatric attention. Don’t they?

It behooves those of us who are journalists today to do our work excellently as a mark of respect not only for this martyred journalist but also for Krees Imodibe, Tayo Awotusin, Bagauda Kaltho, Godwin Agbroko and others who were killed in the course of doing their duties as investigative journalists.

To him, part of the deep trouble with Nigeria is the curse of oil. Because once we started getting the bulk of our revenue from oil, “the farmers left the farms and the youth came to town. Nobody wanted to touch dirt and carry baskets of cocoa, groundnuts and palm kernels. Why? Come to the city and live the easy life. Life was too easy, and nobody waited long enough to ponder the question of where oil was leading the nation. Oil made everything possible, including the Nigerian Civil War.” He then advised that Nigerian, and mankind for that matter, “must make peace with the soil and damn the arrogance and deceptiveness of oil.” In his other essays, Giwa wrote against many of our other ‘nervous conditions’: the inanities in many sectors of our national life. And he summoned his compatriots to high ideals.

As I write this, I have on my desk, an illuminating anthology titled Tell Me No Lies: Investigative Journalism and Its Triumphs. John Pilger, the editor, writes in his lucid introduction:

Secretive power loathes journalists who do their job: who push back screens, peer behind facades, lift rocks. Opprobrium from on high is their badge of honour…

In these days of corporate multimedia run by a powerful few in thrall to profit, many journalists are part of a propaganda apparatus without even consciously realising It. Power rewards their collusion with faint recognition: a place at the table, perhaps even a Companion of the British Empire (read MFR, OFR, CFR etc). at their most supine, they are spokesmen of the spokesmen, debriefers of the briefers, what the French call functionnaires.

If Giwa were alive at this giddy time, in this pond of a country which is now full of bigger sharks, would he have allowed himself to be transformed into one of those corporate pen pushers and journalists described by Pilger as “spokesmen of the spokesmen,” or sheer functionnaires of a powerful few? Through his writings we know the cause for which Giwa was asking people to lay down their lives. But since he once told Professor Toye Olorode, a University of Ife Marxist, in growing anger during a well attended symposium on campus, that he was a Realist, could he have shunned the temptations of wealth, of power and the attendant compromises as an avowed Realist? I honestly do not have a straight answer. But I take consolation in the following exhortation of Salman Rushdie at a gathering of the American Society of Newspaper Editors in 1996:

In free societies, you must have the free play of ideas, there must be argument, and it must be impassioned and untrammeled. A free society is not a calm and eventless place – that is the kind of static, dead society dictators try to create. Free societies are dynamic, noisy, turbulent, and full of radical disagreements. Skepticism and freedom are indissolubly linked; and it is the skepticism of journalists, their show me, prove it unwillingness to be impressed, that is perhaps their most important contribution to the freedom of the free world. It is the disrespect of journalists – for power for orthodoxies, for party lines, for ideologies, for vanity, for arrogance, for folly, for pretension, for corruption, for stupidity, maybe even for editors – that I would like to celebrate this morning, and that I urge you all, in freedom’s name, to preserve.

That was what Giwa too believed. He rose from a humble background to the peak of his profession through hard work. He earned his first degree in English at Brooklyn College (where Dr. Yemi Ogunbiyi taught him briefly) and second degree in Public Communication at Fordham University in the Bronx, all in America, and worked for about four years as a journalist with The New York Times before he came down to Nigeria. He was a flamboyant extrovert who did not know how to keep any secret. His generosity of spirit was electrifying. According to the critical yet forgiving reports of his life in Dele Olojede and Onukaba Adinoyi-Ojo’s Born To Run: The Story of Dele Giwa (a book that the publisher, Chief Joop Berkhout of Spectrum, had to withdraw from the market because of tremendous pressure from the General Babangida junta), we know that Giwa loved the pleasures of life so much and never for a moment wanted to be reminded of the privation he suffered as a kid growing up in Ile Ife. A very sensitive man, he could hold tender moments for a long time. He said in his contribution to the University of Ife Symposium: “I know that poverty is a terrible thing and I would not want to share in it again. I grew up poor, and would not like to live the way I grew up.”

This man who liked to brag about his intellectual power, who loved to say that he was the best journalist in Nigeria, never suffered any fool gladly. He did not glide gently through the world. By the time he was letter-bombed at 39, a truly unique morbid incident in Nigeria at that time, he was just beginning to realise some of his tall dreams. It behooves those of us who are journalists today to do our work excellently as a mark of respect not only for this martyred journalist but also for Krees Imodibe, Tayo Awotusin, Bagauda Kaltho, Godwin Agbroko and others who were killed in the course of doing their duties as investigative journalists. For as Giwa’s essays on journalists and journalism show very clearly, he insisted on nothing but the best from his colleagues. For instance, writing on the senseless murder of Bill Stewart, an American television reporter who was murdered in Nicaragua in June 1979, Giwa threw this challenge in his Press Snaps column in the Daily Times of July 4, 1979: “Any journalist, be it in Akure or somewhere in the Soviet Union, should feel concerned at the wanton killing of any journalist anywhere in the world.” We all must rise to this challenge. To unravel the mystery of Giwa’s assassination is one way of paying part of the debt we owe his living memory. We must cut to the heart of the case of one of our most gifted colleagues. That will be the best tribute to pay him.

Kunle Ajibade, Executive Editor of TheNEWS and P.M.NEWS, is author of the award-winning Jailed for Life: A Reporter’s Prison Notes and What a Country!

END

Be the first to comment