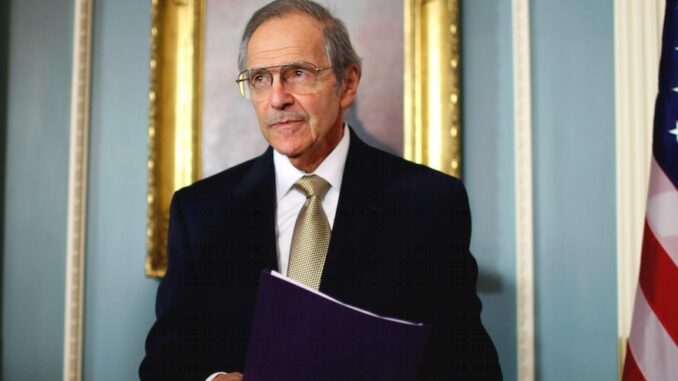

In 2010, former US Ambassador to Nigeria, Princeton N. Lyman, delivered a brutally frank appraisal of the state of the Nigerian nation at the Achebe Colloquium at Brown University, USA. He spoke against the backdrop of popular ‘Nigeria is great’ narrative built on the premise that, as a major oil producer or Africa’s most populous nation and major contributor to peacekeeping on the continent, Nigeria was literally too big to fail. Much of that notion is built on the bogey that the ripple effects of a failed Nigeria would be tremendous.

The former envoy would have none of this argument. In his view, “all this emphasis on Nigeria’s importance creates a tendency to inflate Nigeria’s opinion of its own invulnerability.” He easily burst the bubble of the country’s overrated population saying: “We often hear that one in five Africans is a Nigerian. What does it mean? Do we ever say one in five Asians is a Chinese? Chinese power comes not just for the fact that it has a lot of people, but it has harnessed the entrepreneurial talent and economic capacity and all the other talents of China to make her a major economic force and political force.”

The inference to be drawn from Ambassador Lyman’s position is that Nigeria is conceited. But he is right. What, really, have we to show for our size? From Independence in 1960 to much of the 1980s, Nigeria was highly regarded as Africa’s ‘Big Brother,’ one that most nations on the continent looked up to for direction, especially during the liberation struggles in Southern Africa. By the 1990s to the turn of the 20th century, Nigeria became an index case in what has popularly become known as the ‘squandering of riches.’ Global disappointment in the profligate manner with which the nation mismanaged her leadership potential, in large part, accounted for the frustration that the former US envoy verbalised in 2010.

Ten years after he spoke, few Nigerians are likely to disagree with his position on the ‘fundamental challenges’ we face as a nation. The problems are still multifarious and ranged from ‘disgraceful lack of infrastructure’ to the ‘growing problems of unemployment’ to which we now can add seemingly intractable insurgency, pervasive nepotism and, arguably, a lop-sided fight against corruption. Our ‘oil boom’ became our ‘oil doom’ so much so that, as Lyman rightly pointed out, our position as a ‘major oil producer’ has become largely untenable, what with Brazil launching a 10-year programme to become an oil power; Angola rivalling Nigeria in production capacity and America reducing her dependence on fossil fuel.

Perhaps, nothing better illustrates Nigeria’s reduced weight among her peers than its characterization by the late Libyan leader, Col Muammar Gaddafi, who pronounced with magisterial arrogance that some “nations are big for nothing.” And to think that he made the statement on Nigerian soil in 1982! Though he did not name the nations, the message was not lost on those who could read between the lines.

Today, in 2020, it is difficult to disagree with Gaddafi’s 1982 postulation and Lyman’s 2010 position. This, for the simple reason that Nigeria has not significantly distanced herself from the problems that brought on those harsh international conclusions on the ‘giant of Africa.’ Today, we still grapple with leadership problems, economic crises, insecurity and human resource problems resulting from poor education and our growingly inverted value system.

It is hard to imagine that this is the same Nigeria that once had leaders who could think on their feet and who could call the bluff of any world power. In 1976, then Head of State, General Murtala Mohammed, eyeballed the United States of America, the ‘World’s Policeman’, over the liberation of Angola.President Gerald Ford quickly expressed America’s displeasure at the recognition of the MPLA as the legitimate voice of the people of Angola by Nigeria and some other nations, notably the former Soviet Union, which was locked in a cold war with America.In response, Gen. Mohammed powerfully asserted that “Africa has come of Age.”

At the extraordinary meeting of the Organisation of African Unity (now African Union) held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia on 11 January 1976, Mohammed declared, among others:“when I contemplate the evils of apartheid, my heart bleeds and I am sure the heart of every true-blooded African bleeds. Rather than join hands with the forces fighting for self-determination and against racism and apartheid, the United States policy makers clearly decided that it was in the best interests of their country to maintain white supremacy and minority regimes in Africa… Africa has come of age. It’s no longer under the orbit of any extra continental power. For too long has it been presumed that the African needs outside ‘experts’ to tell him who are his friends and who are his enemies. The time has come when we should make it clear that we can decide for ourselves; that we know our own interests and how to protect those interests; that we are capable of resolving African problems without presumptuous lessons in ideological dangers which, more often than not, have no relevance for us, nor for the problem at hand.”

That assertive speech won Nigeria global respect. That was a time Nigeria could be said to have had focused leadership; when we had leaders who planned for development based on well-thought out blueprints and when leaders tried to judiciously use national resources for development.

Alas, today, Nigeria has lapsed into growing irrelevance in global and even trans-regional affairs owing to the ascendancy of leaders ill-prepared for public office. Few, indeed, have assumed office with any blueprint, which explains why they continue to struggle with governance after several false starts. Rather than being focused on the longer-term promotion of the happiness of the greatest number, they are, like their precursors in the age of slavery, overwhelmed by the ‘Esau Spirit’ of wanting something ephemeral at the expense of something long-lasting. Unlike their ancestors who received mirrors and gunpowder in exchange for selling off their compatriots to foreign slave dealers, current leaders appeared tobe consumed by lust for power and the pursuit of creature comfort as manifested by the possession of private jets, flashy cars, a harem of nubile girls and other indicators of conspicuous consumption.

Their lack of care for the good of Nigeria is the reason they continue to shatter the hopes of citizens and foist numbing frustrations on all of us. The despondency that arose out of broken dreams, perhaps, explains much of the ‘siddon look’ disposition of citizens to governance in the mistaken belief that nothing will change in Nigeria, ‘except God intervenes.’ Our leaders, too, are quick to promote excessive, even violent belief in the ‘God Factor’ for the redemption of Nigeria, knowing that religion shifts attention from their mediocre performance.

But if citizens do not shake off this lethargy, the predicted doom might become a self-fulfilling prophecy. As Ambassador Lyman feared in 2010: “the handwriting may already be on the wall (and) what it means is that Nigeria’s most important strategic importance, in the end, could be that it has failed. And that is a sad, sad conclusion. It does not have to happen.”

I agree with Lyman. He has held a mirror to our faces as we grapple with the challenge of leadership in Nigeria. With 2023 just around the corner, we have yet, again, another chance to redress the leadership shortcomings that are at the heart of Nigeria’s arrested development. Regrettably, however, the country seems, again, to resolutely be headed in the same direction that led to its irrelevance in world affairs. In an age that the Coronavirus pandemic has redefined the future and accelerated development by at least five years, Nigerians are not asking would-be leaders for their development agenda. Instead, we are falling into the same disappointing trap of emphasising and defending issues of ‘our party’, zoning, religion and everything but ‘can-do’ leadership credentials when the rest of the world is forging ahead with issues of renewable energy, cyber security and the like. Our penchant for transitioning to cyclical mediocrity has virtually become a ‘spiritual problem.’ As it were, we now need to save Nigeria from Nigerians. We need to awaken to our civic responsibility and, moving forward, demand for visionary leadership.

Olatunde Johnson is a Lagos-based public affairs commentator

END

Be the first to comment