Madiba Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s views on Ubuntu are useful for the clarification on the term. Of course, such attempt to explain the concept of Ubuntu further should raise questions on the relevance of Ubuntu and Omoluabi to today’s Africa that is throwing away virtues, values and cultures in the pursuit of foreign values and norms being presented as natural for all of mankind.

I had titled the first part of my Zimbabwean experience as, “Quick Visit to Zimbabwe: My Case for the Rekindling of the Ubuntu Spirit in Africa”. I received diverse reactions on this, including on the meaning of Ubuntu. Before writing on the final version of my memorable short stay in Zimbabwe that will be located within a rich history and beautiful nature, I decided to share an interesting exchange that arose from my first write-up, including using the opportunity to explain a bit on the meaning of Ubuntu.

For Madiba Nelson Mandela, Ubuntu represents “the profound sense that we are human only through the humanity of others; that if we are to accomplish anything in this world, it will in equal measure be due to the work and achievements of others”. In effect, individualism that is much cherished in some cultures as the natural state of the human being is not necessarily so in this conception.

Some authors have defined Ubuntu more broadly by suggesting that it is African humanism, a philosophy, an ethic and a worldview. Desmond Tutu, loosely defined Ubuntu as “I participate, I share”. He drew on the principles of Ubuntu to guide South Africa’s reconciliatory approach to apartheid era crimes. For Tutu, “We are different so that we can know our need for one another, for no one is ultimately self-sufficient… The completely self-sufficient person would be sub-human”.

A good illustration of Ubuntu was related in a piece I once read. A group of children were running in a race. A number of them were neck to neck when they noticed that one of them was far behind. They all stopped, went back for the slower child and all ran happily together at her pace. Asked why they did that, they pointed out that happiness shared is far better than one person running to capture a price.

Aside from other reactions on different aspects of my story, and about getting a visa to Zimbabwe with a Nigerian passport, the reaction from a good friend to the first account of my visit cryptically elaborates on the word ‘Ubuntu’ and much more. Unlike many who, in their reactions, felt pity for me, with one promising to raise my experience with officials, I feel I should share the detailed exchange I had with Professor Peter Fogam of the University of Lagos (Unilag) to elicit, if possible, a wider debate on Ubuntu, especially in terms of if such a concept is still relevant in Africa.

As I completed my Ph.D in Political Science at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), I had to drag a fraudulent Iranian to a small claims court. He hired the services of a lawyer. I felt I did not need one, after all I was a freshly minted Doctor of Philosophy. The lawyer made mincemeat of me before the judge. I still won though, on paper, and received a restitution that was much less than I had expected. I guess the Judge was convinced of the fact that I had been defrauded, despite the Lawyer countering most of my arguments with “hearsay” objections and the Judge agreeing with him, most of the times. American courts are not like their Nigerian counterparts. The situation is a little more relaxed, almost like in Judge Judy’s court. There are no intimidating colonial wigs in the hot African sun, for instance. Fela Anikulapo Kuti captured the situation best in his song: “Gentleman”, wherein he derided the African colonial mentality of suit and tie in the stifling African heat on an average day.

I asked the judge the meaning of hearsay. He responded in English that did not make sense to me. I looked and felt daft. But he ruled in my favour, as he seemed to have decided not to allow technicalities to obstruct justice. However, the lawyer insisted on some stupid monthly payment arrangement that I did not have the capacity to oppose. In fact, I was never paid. With this experience, I realised I was not learned as lawyers readily claim to be. This was a major push for me. I went back to school to read law.

Professor Fogam and I come a long way. He was (with the late Professor Adedokun Adeyemi, Professor Yemi Osinbajo, and many others) my teacher in the pursuit of a Bachelors degree in Law at Unilag. Graduating with flying colours, as they say in English, I proceeded to the Nigerian Law School and was called to the Nigerian Bar over 32 years ago. In addition, Professor Fogam, Ms. Bella Okagbue and Professor Osinbajo accompanied Professor Adeyemi to Somalia as part of the United Nations Operation in Somalia (UNOSOM II). In effect, we were co-sojourners for almost two years during UNOSOM II’s search for the peace that continues to elude Somalia in the large part.

The depth of the exchange between Professor Fogam and I on Pan-Africanism, I thought, requires further discussions, including by others, not only on “Ubuntu” but many philosophical and practical issues that should be useful for an African Renaissance, if anything like that is still possible.

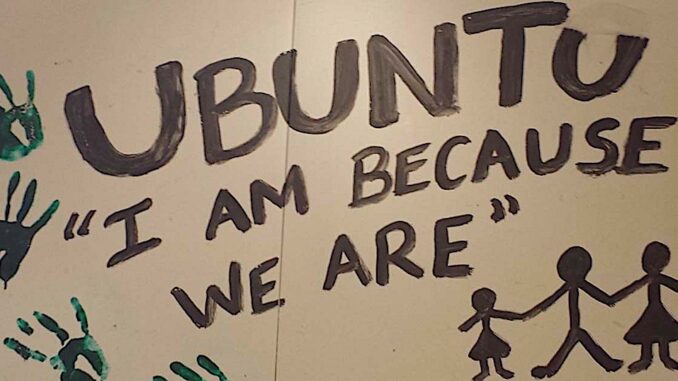

As a fine lawyer should, Professor Fogam started by challenging my use of the word “rekindle” in my title that is restated above. He indicated that he had two concerns with my write-up. He wrote: “First the word ‘rekindle’ means revive. That presupposes that the spirit of Ubuntu had existed before within African countries. With respect sir, that is erroneous. The African colonial history teaches us that there was nothing in common with the colonial territories that needed or needs to be “rekindled”. This is even more so (and that is my second point) when you invoke the spirit of Ubuntu. Ubuntu is a term of South African origin meaning “I am because we are” and translates in real life to mean “humanity towards others”. Our colonial history was just the opposite: Nigerians v Ghanaians; Congolese v Cameroonians; Senegalese v Gambians etc etc. Where was the “humanity” that you are advocating for it to be ‘rekindled’?”

Professor Fogam felt that we should discuss further on another day. Definitely, those days when I was young, our humanity had not become commercialised and the emphasis was on being an “Omoluabi”; this could be a basis for several radio/television dialogues to exchange knowledge, educate, and build towards policies that could ameliorate the African situation. Memories of students sponsored educative exchanges at universities remain very fresh. The public spirited lecturers included names like fast talking-sense personalities like Dr Tai Solarin, Dr Bala Usman, Dr Opeyemi Ola, Professor Bade Onimode, Comerade Ola Oni, Dr Akin Oyebode, Edwin Madunagu, Obarogie Ohonbamu, Funsho Akingbade, Alao Aka-Bashorun, Comrade Hassan Sunmonu, and of course, Gani Fawehinmi, etc. They educated Nigerians at large at platforms provided by students and broadcasted by public and private media dedicated to a better Nigeria, as opposed to today’s profits-oriented media houses, ready to collect advertisements and “brown envelopes” from exploitative interests. In fact, a roundtable or seminar could be a major avenue for additional knowledge-sharing on the major poser by Professor Fogam.

My response to my friend was to pose a number of questions: “What made Nigeria to be concerned about apartheid in South Africa? What made me happy to part with my one-month salary happily, as part of support towards decolonisation and eradication of apartheid in Southern Africa? What made me take my three-year-old daughter to demonstrate in front of Bank of America every Saturday morning while at UCLA, with many other peoples of African descent, pushing for American divestment from South Africa? Tanzania and Zambia sacrificed so much with human and material payments. I concluded that we may not have had enough of the spirit of Ubuntu. But we can surely rekindle that little that is dying or wake up the dead.

His response was very apt. He wrote: “We must not upgrade individual sympathies like you displayed to the spirit of non-existent humanity within us. After all, Ghanaians chased out Nigerians and vice-versa from their countries; even the South Africans that you risked your life and that of your daughter in the protests supporting them, see what they are doing to Nigerians and other nationals in their country today. Prof. why would you have to take a flight round Southern Africa before getting to Harare, why should it take you so long for a sister country to give you a visa, let alone the treatment at airports. “Humanity” implies the quality of being humane; kindness; benevolence. This was killed in us collectively. We look at each other with utter contempt and suspicion and one is worse off if you carry a Nigerian passport”.

My immediate response to these weighty points from my friend was to acknowledge that he had raised valid issues. However, I suggested that we can try to build, if not rebuild our humanity. How we could set about realising such conviction of mine I am unable to articulate in this piece. I hope we all can help towards such an effort.

In sharing my exchange with Professor Fogam, I brought up the Yoruba term “Omoluabi”, which emphasises a human role model that empathises with others in society and an epitome of good character. Such excellent character in society is based on integrity and hard work. No short-cuts that refuse to care about what is left for others in society. It is the opposite of the egoistic self that the dog-eat-dog of a Western competition orientation has foisted on us. Corruption is anathema for an Omoluabi just as it is for Ubuntu. It is certain that corruption kills and eschews Ubuntu and Omoluabi, since a most crucial value for Omoluabi – integrity – is necessarily absent when corruption reins. Corruption is sadistic for it destroys much of the lives of many in society, even if the egoistic conscience-less individual appears to be happy.

Madiba Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s views on Ubuntu are useful for the clarification on the term. Of course, such attempt to explain the concept of Ubuntu further should raise questions on the relevance of Ubuntu and Omoluabi to today’s Africa that is throwing away virtues, values and cultures in the pursuit of foreign values and norms being presented as natural for all of mankind. On Omoluabi, my son once asked me if he should preach about the significance of being an Omoluabi in society to a kidnapper facing him with an AK-47?

Babafemi A. Badejo, author of a best-seller on politics in Kenya, is a former Deputy Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Somalia, and currently a Legal Practitioner and Professor of Political Science/International Relations, Chrisland University, Abeokuta.

END

Be the first to comment