UNABLE to get its act together amid growing demand, Nigeria’s chronic electricity deficit remains an extreme encumbrance to Nigeria’s economic growth and social life. According to the just-released World Bank Sustainable Development Goal 7 report, Nigeria – after Ethiopia and DR Congo – is now the third country with a huge electricity deficit in the world.

Globally, the World Bank SDG 7 report, which covers 2010 to 2020, offers some good news, though. More than one billion people gained electricity access over that decade. Sadly, that excludes sub-Saharan Africa. As of 2020, data generated by the International Energy Agency said Nigeria’s demand stood at 24,439 megawatts. Broken down, industry demand was 4,057MW; residential 14,003MW, and commercial and public services 6,379MW. On June 13, Nigeria’s power generation fell 29 per cent to 3,112MW from 4,115MW the previous day.

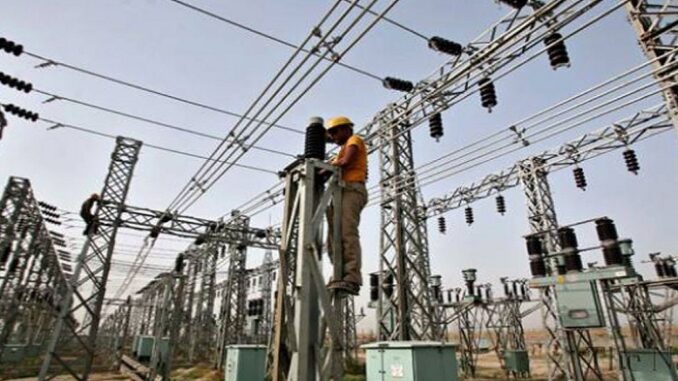

Currently, Nigeria’s total installed capacity from its 22 gas-fired and three hydro plants is 12,522MW. Due to operational inefficiencies, water/gas shortages and corruption, only 7,141MW is available. Even that has never been attained. The IEA estimates the average generation at 3,879MW. This translates to electricity poverty for millions of Nigerians.

The economic cost of the power deficit is considerable. A 2021 report by the Rural Electrification Agency approximated that 80 million Nigerians had no access to grid electricity. According to the World Bank, about 47 per cent of Nigerians do not have access to grid electricity and those who do have access, face regular power cuts. In a country of 211 million people, that means nearly half of the population is excluded from electricity.

No facet of national life is spared. For instance, the University of Lagos is paying a monthly average of N100 million; the Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, pays about N80 million monthly to the distribution companies, but they both still spend significant sums on generators. For industry and commerce, it is estimated that electricity adds between 35 and 40 per cent to the cost of production and services and drains billions of dollars from the economy. The World Bank estimates the economic cost of power shortages in Nigeria at around $28 billion — equivalent to two percent of the Gross Domestic Product.

Successive administrations usually pledge to redress the shortages. Claiming that it inherited 18 years of industry neglect, the Olusegun Obasanjo government formulated a road map on power. A parliamentary probe under his successor, Umaru Yar’Adua, said that the government invested $16 billion in the eight years to 2007. Like many others before it, the probe result was inconclusive, but part of the investment went into the establishment of the Niger Delta Power Holding Company. As of May, the NDPHC, which includes projects in Geregu, Omotosho, Papalanto and Ihovbor, contributed 3,400MW to the national grid. It suffers from gas supply constraints and other issues. There has hardly been any improvement over the decades.

Under the Goodluck Jonathan administration, the DisCos and generation companies were privatised in November 2013 in an exercise marred by fraud. The effect of the rigged exercise is so bad that the DisCos have become a stumbling block in the electricity value chain. There are widespread allegations that they (DisCos) repeatedly reject power from the GenCos. Nearly eight years after the manipulated privatisation, the transmission leg of the tripod is still firmly in government hands.

Erroneously, the government thinks the fundamental issue is money. A lot of money has gone into the sector since 1999 with no significant result. After the Obasanjo administration, the Jonathan administration also committed significant sums between 2010 and 2015. One example was in 2013 when it signed a $1.3 billion 700MW hydropower project in Zungeru, Niger State, with China. The project has yet to operate.

On the same note, the incumbent regime of Major General Muhammadu Buhari (retd.) says it has invested N1.5 trillion as part of its interventions in the sector through the Central Bank of Nigeria in the two years to June 2021. Its stated aim is to increase generation to 11,000MW by 2022 and 25,000MW by 2025 in partnership with Siemens. If so, the regime has a lot on its plate. Idle power is one of them. Represented by the West African Power Pool, Niger, Togo, Benin, and Burkina Faso have expressed their interest to buy unutilised power off Nigeria. That is a paradox since Nigeria has an acute electricity deficit.

The other anomaly is Nigeria’s single grid system. It is too weak. Frequently, it suffers collapse. As of May, it had collapsed twice this year and collapsed on 29 separate occasions in the past three years as per Transmission Company of Nigeria and the Nigerian Electricity System Operator data. To rid itself of this scourge, the grid should be decentralised and privatised, as is the case in the United Kingdom, where the National Grid (UK) is listed on the London and New York exchanges. At the last time, its shares were worth £914.30 each in London and $650.03 in New York. That is a mark of efficiency instilled by the private sector. Nigeria should adopt this and transparently privatise the remaining leg of its power system to reputable operators devoid of the capriciousness of 2013 under Jonathan.

Rather than wholly depending on the centre, state governments should utilise the reform in the sector to build their own independent power systems.

Planning for electric power investment to match the economic demand becomes a vital issue. The World Bank says there is an overreliance on seven gas-fired power plants, which currently supply 59 per cent of the generation. Although gas is abundant, gas plants are hindered by a myriad of problems. The lesson from South Africa is that it generates through different modes, hydro (3,485MW); thermal (48,380MW); wind (2,323MW); solar (2,323MW) and others (580MW), giving that country an installed capacity of 58,095MW.

A stable electricity supply remains the most potent strategy to kick-start the economy. Shubham Chaudhuri, World Bank Country Director for Nigeria, says, “The lack of reliable power has stifled economic activity and private investment and job creation, which is ultimately what is needed to lift 100 million Nigerians out of poverty.” The Buhari regime should break the jinx.

END

Be the first to comment