AFTER a brief period of a clean bill of health, a fresh incidence of over 300 cases of the Circulating Vaccine Derived Poliovirus Type 2, also known as the CVDPV2, in many states of the federation and the Federal Capital Territory, should not be treated with levity. At the last count, the virus is now prevalent in 27 out of the 36 states, giving rise to much concern among the populace and the global healthcare community.

Much as it seemed to have taken the country by surprise, the outbreak of this polio variant is unfortunate primarily because Nigeria is simultaneously contending with an outbreak of Lassa fever, cholera, and the resurgence of different variants of the coronavirus. Since its onset in December 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic has not been brought under control despite immense resources and measures taken by world governments. Tragically, Nigeria had once been declared polio-free.

According to health professionals, an outbreak of a mutant poliovirus is worrisome as it threatens Nigeria’s wild polio virus-free status, given the ability of viruses to mutate, even as it is likely to worsen the nation’s shabby and undermanned healthcare delivery system.

The Executive Director of the National Primary Healthcare Development Agency, Faisal Shuaib, confirmed that the new outbreak was due to immunity gaps in children. This was partly because of the suspension and disruption of the routine immunisation campaign. Mainly, this is traced to the shift in focus to the coronavirus pandemic in 2020. There is also the issue of insecurity in many parts of the country, especially in the polio-endemic northern states where Islamist insurgency and associated terrorism by bandits and Fulani militants have disrupted social and economic activities in many parts. With violence mushrooming, routine vaccination receded. Shuaib however added that all the 36 states and the FCT have completed at least one Novelle Oral Polio Vaccine.

Although polio (poliomyelitis) has endured so much controversy in the politics of global healthcare, it should be emphasised that its virulent and deadly nature has not abated. Medical experts have described polio as a highly infectious viral disease that invades the nervous system. It can cause irreversible paralysis in a matter of hours. The Polio Global Eradication Initiative says, “Polio is spread through person-to-person contact. When a child is infected with wild poliovirus, the virus enters the body through the mouth and multiplies in the intestine. It is then shed into the environment through the faeces where it can spread rapidly through a community, especially in situations of poor hygiene and sanitation.”

Given the nature of transmission, through foods and drinks contaminated with infected faeces and the symptomless state of infected persons, the World Health Organisation considers a single confirmed case of polio paralysis to be evidence of an epidemic. In Nigeria, that is double trouble. A 2019 UNICEF survey listed Nigeria as having the highest incidence of open defecation in Africa and the second highest in the world, with 46 million people practising it. All this calls for concern, especially at a time the Ministry of Health and its stakeholders are grappling with an outbreak of Lassa fever and an ongoing coronavirus pandemic.

Indeed, with its resources, Nigeria has no reason to be a polio state. On August 25, 2020, Nigeria became the last country in Africa to be certified free from wild polio after the last reported case in Borno in 2016. However, in these precarious times when health workers are overwhelmed with COVID-19, cholera outbreak, and Lassa fever management, Nigeria must do all it can to regain its WPV-free status and stop the cVDPV2 transmission in communities. While the WPV is the most common form of poliovirus, the circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus is another form that can spread within communities, which Nigeria is currently experiencing.

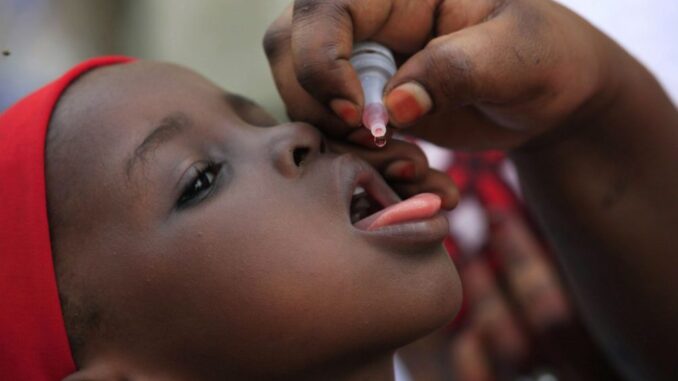

As the WHO has advised, immunisation with the appropriate vaccines remains the most potent prevention measure against polio. This being the case, the government, health authorities and community leaders must work together to ensure that children in the affected states are properly immunised. New strategies and curtailing insecurity are important.

Nearly a decade ago, when Nigeria was embroiled in the polio controversy, leading to the death of foreign medical workers and immunisation officers in Kano State, experts and stakeholders implicated clerics and journalists suspected to have been at the forefront of misinformation. Given the recent outbreak and its widespread nature, it is not unlikely that such negative action would be recalled. In readiness for such, Nigerians must guard against misinformation and mischief-makers.

This is where those at the forefront of information gathering and dissemination, especially clerics, community leaders and the media, should demonstrate a high level of information management. As they have always been reminded, they should be conscious of the moral demands of their roles to the community and society at large.

Like COVID-19 and malaria, polio is a serious health issue. Nigerians, either as individuals or collectively, must rid themselves of the cultural and religious inhibitions that make them victims of not only polio but also of other endemic afflictions. Communities must eschew all forms of politicisation of the polio outbreak. Concerted efforts should be made to discourage misinterpretation of immunisation exercises. It behoves them to eschew all subversive tendencies and inclinations towards disinformation and misinformation.

In states where polio cases have been reported, the state governments should empower and mobilise their local government officials to mobilise traditional authorities, community, and religious leaders to sensitise their fold on the resurgence of polio. While polio is prevalent among children aged five and below, it can infect persons of any age.

Therefore, beyond the conscious aggressive immunisation of children in affected areas, there should also be emphasis on good sanitation among the populace. This is very crucial because poverty and poor sanitation are becoming widespread with the dwindling economy and dismal healthcare regime. Besides, communities need to partner with philanthropic organisations and harness resources towards a polio-free country.

END

Be the first to comment