NIGERIA is engaged in health wars on multiple fronts, deepened by poor health infrastructure, insufficient investment in healthcare, inaccessibility of quality health services and a stagnating health workforce. Across the country, silent killer diseases such as hepatitis have continued to gain ground with over 18.2 million persons affected. The federal and state governments should take strong, consistent measures to combat this deadly ailment.

Described by the World Health Organisation as a disease caused by an inflammation of the liver that is triggered by a variety of infectious viruses and non-infectious agents, the organisation stated that the disease could lead to a range of health problems, some of which can be fatal.

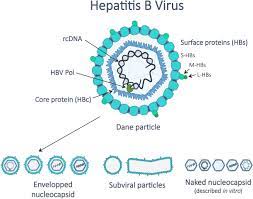

There are five main strains of the hepatitis virus, referred to as types A, B, C, D and E. While they all cause liver disease, they differ in important ways, including modes of transmission, severity of the illness, geographical distribution and prevention methods. Types B and C lead to chronic disease in hundreds of millions of people and together are the most common cause of liver cirrhosis, liver cancer and viral hepatitis-related deaths.

Data from the WHO revealed that while an estimated 354 million people worldwide live with hepatitis B or C, and for most, testing and treatment remain beyond reach; every 30 seconds, a person dies of hepatitis-related disease, amounting to an average of 3,600 deaths every day.

The global health organisation says that both hepatitis B and C, which are regarded as the commonest of the five strains, cause an average of 1.1 million deaths and three million new infections globally every year.

The Minister of Health, Osagie Ehanire, deplored the high number of Nigerians — 18.2 million — battling viral hepatitis. Partly, he blamed this on lack of public awareness, non-reporting, poor diagnosis, and lack of treatment of hepatitis B and C in the country.

As it is a global scourge, Nigeria’s health authorities need to strengthen collaboration with international organisations and other countries to tame the menace. In his recent statement ahead of the 2022 World Hepatitis Day that comes up every July 28 to raise global awareness, the Director-General of the WHO, Tedros Ghebreyesus, noted that though many countries had participated in the hepatitis elimination plan, many were yet to commit fully to its elimination by 2030.

Tedros said, “Too many people still miss out on services to prevent or treat hepatitis on services to prevent or treat hepatitis, including infants in Africa who miss out on the crucial hepatitis B vaccine birth dose.” He reminded African countries of their pledge to deploy resources toward the elimination of hepatitis and to regard viral hepatitis as a public health threat.

Many African countries that committed to eliminating the disease have however either not ratified their guidelines or not increased access to hepatitis care. The good news is that Nigeria is one of the 28 African countries that have developed national plans to eliminate the disease. Implementation has however been inconsistent. This should change.

There are different forms of hepatitis and each is attributed to a different type of virus. Unfortunately, most people who have the most serious forms of the disease, particularly the B and C viruses, are unaware of infection. This allows the infection to spread unchecked, leading to serious damage to the liver.

Hepatitis B is very common. It is spread through infected body fluids, either through sex with an infected partner, at birth (from an infected mother to her baby), direct contact with open wounds or blood of an infected person, sharing syringes, razors, or toothbrushes with infected persons.

The mainstay strategy for managing hepatitis B is prevention through the administration of a vaccine. It is also treatable, through oral antiviral drugs which in most cases must be taken for life. This is because the treatment, in most people, only leads to the suppression of the viral load and not its complete remission. To prevent its progression, it is highly recommended that treatment begins within the first three months of infection.

Though Nigeria had disruptions in its childhood immunisation programme due to the coronavirus pandemic, there is a need to commit more domestic resources to fast-track hepatitis elimination. Nigeria can recover some of the lost time. It only requires taking more innovative approaches to promoting access to information and services.

Cape Verde, Uganda, and Rwanda have committed more resources to ensure a 99 per cent birth dose vaccination rate, free national hepatitis B treatment and free treatment for hepatitis B and C respectively. This demonstrates what political will can achieve. Nigeria should roll out and implement similar policies. Cape Verde’s government funds all vaccine services, and implemented hepatitis screening for pregnant women (since 2002) and a recommended vaccine (since 2010), having maintained almost 98 per cent vaccine coverage for decades.

Mobile health services have also worked effectively in Madagascar and South Africa in increasing access to vaccines and family planning services. States and LGs should use mobile clinics to reach communities in far-flung areas and enable health workers to provide hepatitis screening and treatment services.

These should be supported by mainstream and social media platforms, as well as mobilising opinion and community leaders to spread awareness. There should be community outreach campaigns such as those run about HIV/AIDS, the dangers of drugs and substance abuse and road safety among others.

Hepatitis services are not as adequately funded as other priority areas such as HIV, immunisation, and reproductive health. Hepatitis care needs to be integrated in some of the programmes promoting access to healthcare. This would help ensure that regular hepatitis screening is made available to women visiting health facilities for antenatal services, or to patients taking treatment for HIV infection.

Nigerians are afflicted by too many illnesses; the various governments should accord priority to the wellbeing of the people. They should act quickly to eliminate hepatitis and reduce the people’s health burden.

END

Be the first to comment