It was the vibration of the ringing phone that jolted him from sleep.

The room was dark and cozy. The air conditioner hanging on the wall worked silently to keep the room as cold as London where he returned from earlier in the morning.

Outside, the sun was blazing as the power generator churned out alternating currents to keep the air conditioner alive.

“Alhaji, we have a deal!” the voice on the other end of the line said as Rabiu Hassan pressed the phone against his ear.

“I have spoken with the NSA – National Security Adviser – and he has given his approval. Let’s rally and seal the deal as soon as possible,” the caller said before hanging up.

Mr. Hassan, a shrewd defence contractor, was happy to learn the good news. The exhaustion he had sought to relieve with the afternoon nap, in his Abuja home, didn’t seem to matter anymore.

It was Saturday, November 19, 2011 and his life was about to get merrier.

Earlier that morning, both Mr. Hassan and his caller, Salihu Atawodi – chairman of the Presidential Implementation Committee on Maritime Safety and Security – returned to Abuja from London on a British Airways flight.

A few days earlier, Mr. Hassan, chaperoned by business partners, had escorted Mr. Atawodi’s party, which included friends and colleagues, to go inspect brand new military boats that were up for auction at giveaway prices in Amsterdam, Netherlands.

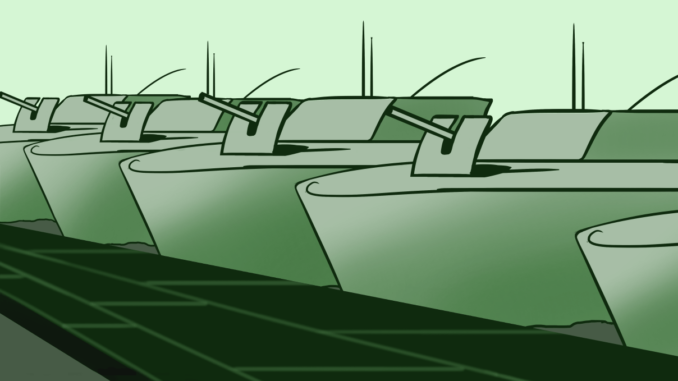

The boats, known in the military marine hardware market as K38 Catamaran assault crafts, are exceedingly fast and agile attack military boats renowned for powerful performance on shallow waters.

Read prologue to this story.

K38 History

In 2008, during the first rise of militancy in the Niger Delta, one of the earliest problems the Nigerian military faced combating the militants was the lack of assault crafts to navigate the shallow waters of the creeks in the region.

In response, the Umaru Yar’Adua-led Nigerian government contracted Amit Sade, an Israeli contractor and CEO of Doiyatech Nigeria Ltd to supply 20 units of K38 combat boats to the Nigerian Army.

Mr. Sade’s Doiyatech does not make boats neither does he own any other military hardware company. But he was the only handpicked bidder for the contract worth N3.12 billion at the time. There was no bidding process as contemplated by Nigeria’s public procurement law. In the contract, each boat was worth N156 million.

He was immediately advanced 80 per cent of the total cost of the 20 boats with a promise that the balance would be paid once supplies are completed.

With a bank account full of money, Mr. Sade left for the Netherlands where he outsourced the contract to TP Marine, a two-man shipyard.

He did not deliver on any of them, a report by the presidential panel which recently investigated military procurements in Nigeria revealed.

The contractor had also fronted for TP Marine to land jobs with the Nigerian Navy and the Dutch had no qualms taking on this new project.

A few months later, he returned to Nigeria with eight boats. The Nigerian military received the few he had and never bothered to ask for the outstanding 12. They seemed to have been impressed that he at least partly delivered on the job.

However, in anticipation that Mr. Sade would return to claim the remaining 12 boats for which he placed order, TP Marine continued production.

But the contractor never returned.

Four Years Later

Four years later, Mr. Hassan, the Abuja-based Nigerian contractor was prospecting for military boats when some other Israeli contractors operating out of the Nigerian capital, linked him to TP Marine.

Hours after the introduction, he had his first meeting with Bjorn Neeven and Roland Kraft, owners of TP Marine in Paddington Hotel, London. That meeting was brokered by the new agents.

The boats were selling for N49 million each – a smaller fraction of the huge and overpriced N156 million for which Mr. Sade sold each boat to the Nigerian military.

TP Marine was, however, not willing to sell to a Nigerian company and they opened up to Mr. Hassan why that was so.

The boats, in the first place, originally belonged to Nigeria courtesy of the 2008 contract with Doiyatech.

They were avoiding legal complications with the European Union and Mr. Sade. But they could not also hold on to the boats any longer as they were accruing demurrage and digging a hole in the company’s finances.

TP Marine offered Mr. Hassan a lifeline. They would sell to him if he could get a non-Nigerian company to buy from TP Marine before reselling to him.

“My brother, that was one of the sweetest deals I ever got in my life,” Mr. Hassan told PREMIUM TIMES. “I immediately grabbed the chance and committed myself.”

Half of the 12 outstanding boats were done, but for armoring. The other half lay in casts.

Excited, both parties entered a deal through the Israeli agents before departing London.

When Mr. Hassan committed to buying these boats in London, he had no customer waiting to buy from him. He was only confident he would find one.

In Abuja, he was faced with two immediate challenges. First, he needed a non-Nigerian company to pose as the direct buyer from TP Marine. Secondly, he needed someone to buy the boats from him so he can make a huge profit.

To solve his first challenge, Mr. Hassan turned to Mustapha Mohammed, a much younger business associate.

Mr. Mohammed stepped forward with his defunct UK Registered company, Hypertech UK limited.

With his first challenge resolved, Mr. Hassan began marketing his boats.

His first point of call, he said, was Bello Haliru Mohammed, the defence minister at the time.

“I gave him a verbatim account of my London meeting with the owners of TP Marine,” the contractor said.

After describing how notorious Mr. Sade was in the defence contracting industry, the defence minister handed Mr. Hassan a five-page document containing a list of 31 failed defence contracts.

Mr. Sade’s companies – Doiyatech and D.Y.I Global Services Limited – dominated the list of defaulting contractors accused of not delivering for jobs they were paid.

The defence minister sounded helpless and powerless in checking Mr. Sade’s alleged antics, Mr. Hassan recalled.

When contacted, the minister, now facing trial for allegedly stealing public funds ahead of the 2015 general elections, texted a PREMIUM TIMES reporter saying he could not remember the meeting.

He could also not remember the five-paged document despite the fact that the defence ministry, in that same document and during his leadership, described the K38 military boat contract as having been “stepped down”.

When confronted with the documents, he dismissed them as Tenders Board document.

“Ministers were not members of the board during my time,” he said.

At about the same time that the minister had that initial conversation with Mr. Hassan, the defence ministry also received a letter from TP Marine intimating it of the 12 boats abandoned in the Netherlands by Mr. Sade.

Neither the defence minister nor the ministry acted to recover either the boats or monies paid out to Mr. Sade.

Mr. Hassan capitalised on the ineptitude and financial recklessness of officials at the defence ministry. He continued marketing the boats around government security agencies in Abuja.

Soon, he landed a bright green prospect in PICOMSS.

PICOMSS enters the fray

In response to rising banditry by sea pirates in the Gulf of Guinea and intense pressure by the International Maritime Organization on him to act decisively, former President Olusegun Obasanjo established the Presidential Implementation Committee on Maritime Safety (PICOMSS) on July 1, 2004.

The idea was a short-term solution to sustain economically beneficial maritime activities in the gulf as security agencies charged with securing the waterways kept failing in their responsibilities.

Somehow, what was conceived as an ad hoc committee remained alive almost a decade later.

Its loosely defined job description meant that it almost often strayed into the responsibilities of the over a dozen other government agencies securing the maritime sector.

In 2012, facing stiff opposition from some maritime security agencies in the country, its chairman, Mr. Atawodi, launched an aggressive push to make PICOMSS a permanent government agency backed by law.

At the time Mr. Hassan marketed the boats to him, the PICOMSS boss was lobbying members of the National Assembly to pass a law making the agency a standing government parastatal.

Acquiring these boats fitted into his grand plan to establish authority in the sector and win over more undecided lawmakers, Mr. Hassan quoted Mr. Atawodi as telling him at the time.

He was eager to buy them. All six.

In his private office in Abuja, he had made 2D models of the boats with PICOMSS boldly printed on its shells.

Mr. Atawodi was neither interested in calling out Mr. Sade for disappearing with the initial contract funds nor fascinated about making any move to recover the boats already paid for.

In fact, he told PREMIUM TIMES the boats “technically” didn’t belong to Nigeria, after arguing he was initially ignorant of the boats’ history.

Months after learning about the boats, he assembled a team and they flew to the Netherlands, via London, to inspect them. On November 18, 2011, TP Marine gave the delegation a two-hour on-sea performance tour with the boats.

On the spot, they decided to buy. A sales contract was drafted immediately but there was a little problem.

How Much Will You Buy?

As customary with procurements within the Nigerian security industry, the cost is neither driven by economics or any known pricing mechanism. It is rather driven by how much the buyer – the government guy – is willing to pay without hurting the profit margin of the contractor. A consideration will also be made for the different levels of bribes to be paid to facilitators.

TP Marine offered the boats to Mr. Hassan at N49million each – at the prevailing Naira/Euro exchange rate in 2012.

The total cost for the six boats came to N294million.

With armoring upgrades, logistic and profits, Mr. Hassan said he initially set the total price at approximately N600million.

In the contract drafted in Amsterdam on the day of the inspection, the Atawodi team excessively inflated the contract to approximately N3.1 billion.

PICOMSS had limited funding. Mr. Atawodi was, therefore, unable to funnel the entire N3.1 billion from PICOMSS. He needed to draw from a special funding pipeline he had with the then National Security Adviser, Andrew Azazi.

The call to Mr. Hassan after the team’s arrival from the inspection trip was to inform him the NSA has been co-opted into the deal.

In an interview with this newspaper, Mr. Hassan blamed Mr. Atawodi for this astronomical contract inflation which would have seen collaborators sharing over N2.5billion

“There was nothing to hide,” he said. “I was supposed to deduct my own and give them the rest. With the National Security Adviser involved, I was fine with it. He is after all the chief accounting officer of Nigeria’s national security. If wants to buy it for (Euros)100 billion, who am I to say no?”

Mr. Atawodi did not deny inflating the contract but he claimed the excess N2.5 billion was for amouring of the boats.

“These things are expensive, you know,” the former PICOMSS boss said.

He also argued that he believed the boats were selling at non-auction retail prices.

The Looting Regime

Ten days after the inspection trip, even before his team submitted a report of the trip, Mr. Atawodi credited Mr. Hassan’s newly established Eco Bank account with N620.918 million from PICOMSS’ commercial bank account.

The payment was not immediately invoiced or documented in any other form. It had no logical correlation with the N2.5billion he and his collaborators planned to pocket. It was also higher than the original N600billion Mr. Hassan demanded.

Mr. Hassan said Mr. Atawodi followed up the curious fund transfer to him with a telephone call requesting him to hurriedly convert the money to United States dollars and hand over to the PICOMSS chairman that same day.

He claims he complied and delivered the first tranche to Mr. Atawodi in a Ghana-Must-Go bag. Meeting point that night was IBB Golf Club at the upscale Asokoro District of Abuja.

Mr. Atawodi denied this narrative, saying it never happened.

In 2015, the EFCC charged both men to an Abuja court for defrauding Nigeria of the same N620 million.

In court, Mr. Atawodi claimed the transfer was an upfront payment for the boats. Mid 2017, another Abuja court acquitted him.

Mr. Hassan’s bank statement, however, showed clearly that the controversial fund transfer happened between the two men.

A Conman’s Death

In the Nigerian defence contracting industry, double-dealing is perhaps the only commodity that can be considered more abundant than public monies to steal, insiders say.

After that first payment, Mr. Atawodi wrote a memo to the National Security Adviser, Mr. Azazi, requesting the release of N3.1 billion for the purchase of the boats.

The National Security Adviser unexpectedly foot-dragged. At the time, he favoured giving more maritime security control to an ex-militant warlord, Tompolo. In fact, the NSA had prepared a memo to the president demanding the scrapping of PICOMSS.

But the defining moment for this contract came after Mr. Hassan had a meeting with the NSA to market the boats.

It turned out that the PICOMSS chairman was trying to outsmart the NSA.

“The National Security Adviser was told a completely different thing and was never a party to fixing that amount,” Mr. Hassan told PREMIUM TIMES.

The steps taken by the NSA after learning of the price variation are what defines government contracting in Nigeria.

Read that in part four of this series…

Illustrations by Micheal Anderson.

Additional reporting by Samuel Ogundipe, David Ndukwe, and George Ogala

Be the first to comment