A review of old U.S. diplomatic cables by PREMIUM TIMES has shed fresh light on the circumstances under which Justice Taslim Elias was controversially sacked as Chief Justice of Nigeria (CJN) in August 1975 and how the military government made amends by promoting his election to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) at The Hague two months later.

Until the suspension of Walter Onnoghen by President Muhammadu Buhari, Mr Elias was the only CJN removed from office.

Other former holders of the office left upon their attainment of the retirement age, which now stands at 70 years.

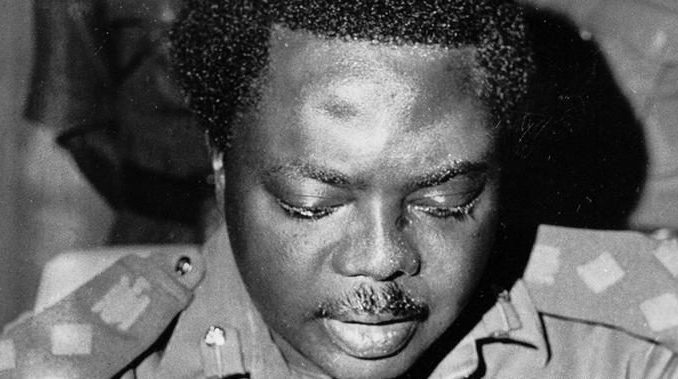

Mr Elias was sacked by General Murtala Muhammed, the Nigerian Army major-general who became Head of State after the July 29, 1975 coup. The putsch ended the nine-year military government of General Yakubu Gowon.

Following the coup, the new military regime launched a ferocious purge of the public service. The exercise was so massive that the American embassy in its cable of August 22, 1975 to Washington described it as being of “avalanche proportion.”

Caught in the sweep were senior armed forces officers, including all military officers from the rank of major-general and above, and 94 senior police officers; hundreds of senior federal and state civil servants, nine career ambassadors and some judicial officers.

But the name that surprised Nigerians and outside observers most on the list of those sacked or forced to retire was that of Mr Elias.

One of Africa’s greatest jurists, he had been appointed CJN only three years earlier in 1972.

Before the appointment, he was the Attorney-General and Federal Commissioner of Justice. He was first appointed Nigeria’s Attorney-General and Minister of Justice in 1960 and served in the capacity through the whole of the First Republic.

After the first Nigerian coup d’état in January 1966, the short-lived military government of Johnson Aguiyi Ironsi removed him from the position. However, he was reinstated in November of that year after Mr Gowon became Head of State.

Earlier in 1966 after his sack by Mr Aguiyi-Ironsi, the University of Lagos appointed Mr Elias as a professor and dean of its Faculty of Law. When Mr Gowon reinstated him as Attorney-General and Federal Commissioner for Justice, the jurist combined the position with his chair at the University of Lagos.

When the military government announced his removal on August 20, 1975, it cited his health as reason for the action. To show he retains its regards, the government issued a statement praising his contributions to the nation and profession of jurisprudence.

However, when the American Charge d’affaires called on Mr Elias at his residence on August 27 “to express regret at his retirement”, the jurists told him that health had nothing to do with his removal.

According to another American cable of August 29 that year that has been published by Wikileaks, Mr Elias told the envoy the majority of the members of the Supreme Military Council did not support his removal and that it was regretted by the country’s new leadership.

“Taslim Elias was grateful and reassured Charge (d’affaires) that health had nothing to do with his removal,” the embassy reported in the cable.

“He said a ‘small caucus’ composed of persons (unidentified) in and outside the current government was calling the shots in the FMG (Federal Military Government) and had included his name among those to be sacked.

“When other members of supreme military council learned of this, a majority of them, including several key northerners, objected strongly. Was decided to rescind the ouster, but at that point announcement of it appeared in the Daily Times; FMG was embarrassed to recant publicly, and therefore tried to excuse it by alleging Elias’ ill health.”

But that account is markedly different from the one given by former President Olusegun Obasanjo in his book, Not My Will.

Mr Obasanjo, at that time a lieutenant-general, said those who decided on the sack were himself, Mr Muhammed and the then Attorney-General and Federal Commissioner for Justice, Augustine Nnamani.

Mr Obasanjo was the de facto deputy to Mr Murtala as the Chief of Staff Supreme Headquarters.

According to his own account, the military junta decided to extend the purge of the public service to the judiciary because “The judiciary had lost credibility and confidence in it had greatly eroded when we came to government.”

He continued: “A Nigerian eminent legal luminary confirmed the situation by saying that he had made up his mind to stop appearing in courts. The situation was that bad and a desperate situation requires a drastic action.”

Mr Obasanjo then explained why the axe fell on Mr Elias, in spite of the fact that “his legal competence was not in doubt and we also acknowledged that he was a great academician.”

He wrote: “His management competence and integrity to administer the judiciary was called to question especially, as a result of the apparent muddle, confusion and ineptitude by the judiciary previously.

“One issue of integrity that was raised and the accusation against him was the empanelling of a Supreme Court body to hear the appeal of a land case brought by the Chief Justice’s brother on which the Chief Justice was alleged to have sat, and he chaired that panel which decided in favour of his brother. If it was right legally, we considered it improper and offensive to public morality.

“We considered his capacity to administer the judiciary thereby impaired. He would not be able to move along with the new order and new dispensation. He had to be relieved of his assignment.

“It was made known to me by a colleague of Justice Taslim Elias much later after my period in government that Dr. Elias could lose his sense of propriety on issues involving his brother who was his great mentor. This could possibly explain his behavior in this respect.”

The government’s embarrassment over the sack grew as “hundreds of friends and well-wishers (200 to 300 a day) descended on Elias’ residence to express shock, disapproval and concern.”

Mr Elias was immediately replaced with an outsider from the Supreme Court, Darnley Alexander, a long-time Caribbean resident in Nigeria who at that time was the Chief Judge of Cross River State.

Two months later, nevertheless, the military government wrote the secretariat of the International Court of Justice, proposing Mr Elias as the Nigerian candidate for the election for African seat on the court.

Mr Obasanjo explained why the junta decided to help a man it just dismissed from his role at home to get another prominent one on the global stage.

“It was in consideration of Justice Taslim Elias’ distinguished status as a Jurist, if not as an administrator and a good manager of judicial establishment and to indicate that our intentions were based purely on the fact as we saw them that we recommended him for appointment into the International Court of Justice at The Hague.

“Not only did we recommend him, we also fought to get him elected against other African candidates who were nominated well ahead of him.”

Ironically, Mr Gowon had “offered” him the ICJ seat earlier in the year, Mr Elias told the American envoy. He said he declined the offer, “believing he could serve Nigeria better at home.”

“Now, however, with changed circumstances, he is very much interested in ICJ candidacy,” the American embassy stated in the cable.

“Embassy believes Taslim Elias will be a good choice.

“Embassy recognizes it is not in position to evaluate relative merits of various candidates (Kenyan High Commission has circulated note requesting support for Justice Waiyaki) for seat on ICJ currently held by Nigeria but would simply note:

“(a) Justice Taslim Elias is a man of stature, highly respected in international circles, recently named a member of the elite International Commission of Jurists;

“(b) Trained in the UK, Elias was initially cool to the U.S. but has established extensive contacts with U.S. jurists and has become keenly interested in U.S. legal system, which he believes has much to offer Nigeria. Elias has encouraged use of U.S. law texts in Nigeria and has sponsored training of Nigerian law librarians in the U.S. He is interested in federalism and has been looking to the U.S. Constitution for ideas that might be incorporated in a new constitution for Nigeria.

“(c) U.S. support for Elias’ nomination to ICJ would help FMG salvage its handling of Elias “retirement” and should therefore be appreciated by new leadership.”

Even though he recognised that it was already late for his candidacy to be proposed; as nominations were supposed to be made in June for the election, Mr Elias told the envoy “he would be most grateful if U.S.G. (United States Government) could express an interest in his candidacy or lend its support in any way.”

Apparently, the Americans and their allies did just that, as Mr Elias was in October 1975 elected by the General Assembly and the Security Council of the United Nations to the International Court of Justice at The Hague.

In 1979, he was elected Vice-President by his colleagues on that Court. In 1981, after the death of Sir Humphrey Waldock, the President of the Court, Mr Elias took over as Acting President.

In 1982, the members of the Court elected him President of the Court. He thus became the first African jurist to hold that honor. Five years later, Mr Elias was also appointed to the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague.

He died on 14 August 1991 in Lagos, his home state, at the age of 77 years.

END

Be the first to comment