The ranks of Africa’s “big men” thinned further as popular uprisings in Algeria culminated in the ouster of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s regime and that of his counterpart in Sudan, Omar al-Bashir, this month. These dictators rode roughshod over their people for decades, caused serious economic hardships and ran utterly corrupt governments. Now, their time is up.

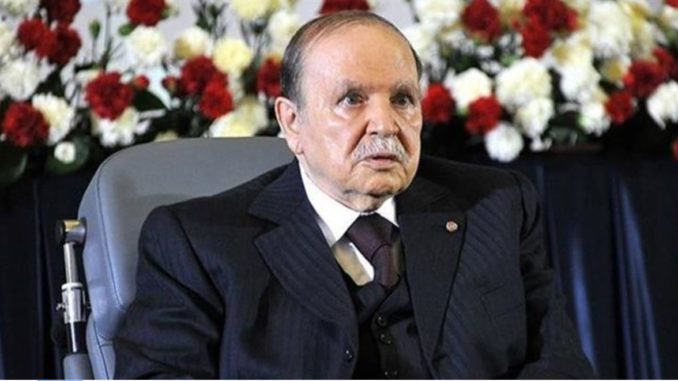

The political events in the two countries were unpredictable. Bouteflika, 82 years old, had since 2013 been a recluse, having been struck down by a stroke. As a result, he has been confined to a wheelchair. Despite this debilitating health condition, which rendered him an ineffectual president, he still indicated interest in running in the presidential election, earlier billed for this April, to the chagrin and fury of his people. That bid was his fifth, having assumed the mantle of leadership in 1999. This obsession with power sowed the immediate seed of the six weeks of rebellion that began in February. On April 3, sensing danger as the military joined the masses to ask him to quit, he resigned. The president of the upper house – Council of Nations – Abdelkader Bensalah has stepped in for 90 days as an interim leader, pending the election that will produce Bouteflika’s successor.

The tidal waves of the Arab Spring in 2011 that swept President Zine Ben Ali of Tunisia, Hosni Mubarak of Egypt and Muammar Gadaffi of Libya out of power missed Bouteflika’s scalp, because of his deft manoeuvres in response. He suspended an extant two-year state of emergency and met other key demands of the protesters. But the latest event has proved that “people power” is a sword an unpopular regime cannot duck for too long.

Algeria under Bouteflika was in the hands of what was described as a “System,” the nexus of compromised politicians, businessmen and the military, who had kept democracy firmly at bay. A reckless election bid on a wheelchair might have pulled the trigger, but the periodic convulsions from spikes in prices of basic food items, unemployment and stagnant economy that bred cuts in public spending with the fall in oil prices laid the foundation. Other toxic elements were reduction in social services and lack of freedom of speech. The outcry of political restructuring is now the ultimate demand of the protesters.

As the Bouteflika regime was crumbling in Algeria, the Sudan scenario was unfolding in a more dramatic and daring manner. Al-Bashir superintended over the country for 30 years, ravaged by war, genocide, soldiers’ notoriety for raping women, torture, famine, corruption, rising costs of food and international isolation.

The political situation in the two countries again, are in fact, lessons in nation-building to citizens asphyxiated by crass leadership failure that folding their arms in resignation is not the ideal solution; after all, the philosopher, Joseph de Maistre, underscored it, that people get the leaders they deserve. It is another confirmation that protest is so fundamental for human rights. Events in Algeria and Sudan show that public demonstrations and marches empower people by showing them that there are thousands of people who think the same.

For the disgraced Sudanese ruler, nemesis simply caught up with him when his government toyed with the idea of an increase in the price of bread in the twilight of 2018. The move was greeted with a national protest, which he tried to quell. The protesters hit the bull’s eye by demanding an end to his regime in February. It is an audacious dig no dictator tolerates. His response was true to type: In February, he declared a state of emergency; sacked all state governors and replaced them with his loyalists in the military and reshuffled his cabinet.

But the more he dug in, the more he became insecure as the protest gathered momentum. So committed and fearless to the cause, Sudanese daily thronged to the front of the military headquarters in Khartoum with the same plea. On April 11, Sudan’s military announced that they had taken over from al-Bashir. The defence minister, Awad Ibn Auf, announced a two-year interim government headed by him; released all political prisoners, suspended the constitution and imposed a nation-wide curfew.

Impressively, defiance to this order of things has remained resonant. A military government, replacing al-Bashir’s pariah regime is well defined in one of the chants that belched out from the crowd: “we do not replace a thief with a thief.” Indeed, the military hierarchy’s replacement of Auf, an ally of al-Bashir, with another army general, Abdel al-Burhan, is a sleight of hand.

Military rule is no longer fashionable or acceptable across the world. With the messianic pretentions of their helmsmen at inception, promises to hand over power to democratically elected governments within a short while; they end up transmuting themselves into so-called democratic leaders; leaving their countries in total ruins when they are eventually humiliated out of office. The Democratic Republic of Congo and The Gambia are good examples. This is why the rejection of diarchy – a transitional government comprising the military and civilians by the Sudanese Professional Association that provided the intellectual undergird for the uprising – is commendable.

Al-Bashir is an archetype of a villain, linked with $9 billion of looted funds by Wikileaks, according to a report by the whistle-blowing website in 2010. The $130 million found in his house seems to further strengthen global perception of his crookedness or notoriety. He must also pay for his bloody role in the Darfur genocide in which about 300,000 lives were lost, according to United Nations estimates. The International Criminal Court had ordered his arrest and trial while in office, for committing crimes against humanity. The only fitting epilogue to his reign should be to hand him over to the ICC for trial.

Africa’s big men are terrors to their countries, they should go. They should learn some useful lessons from the fates of their fellow travellers in Algeria and Sudan. As the late Walter Rodney, a prominent Guyanese historian, political activist and academic, once said, “Human spirit has a remarkable capacity of rising above oppression.”

END

Be the first to comment