All of them were hired by all of us to do a job, and each is to be judged on its own merit. They are not to be defended and protected simply because you like the one and you dislike the other; they are to assessed independently based on the job they were given to do, and how they did that job.

I have heard this bit of nonsense constantly – seen it sometimes on social media, in comment boxes or random commentary: that because I actively, enthusiastically and unrepentantly threw personal and professional weight behind the election of a political office holder, I have somehow lost the moral right to speak out against him.

Nonsense.

As long as a president or a governor or a senator, or a representative is a public servant, paid for and employed by the Nigerian people (tax paying or not), no one loses the right to question him, to declaim him, to demand from him.

Wherever we learnt this nonsense from, as a matter of national urgency, we need to go back to that particular spot, and unlearn it, and while we are at it, get our basic self-worth back.

This is cognitive dissonance. And it is one that we have to begin to address, if we are to have a nation worth having, and if we are to stop getting the types of governments that we currently richly deserve.

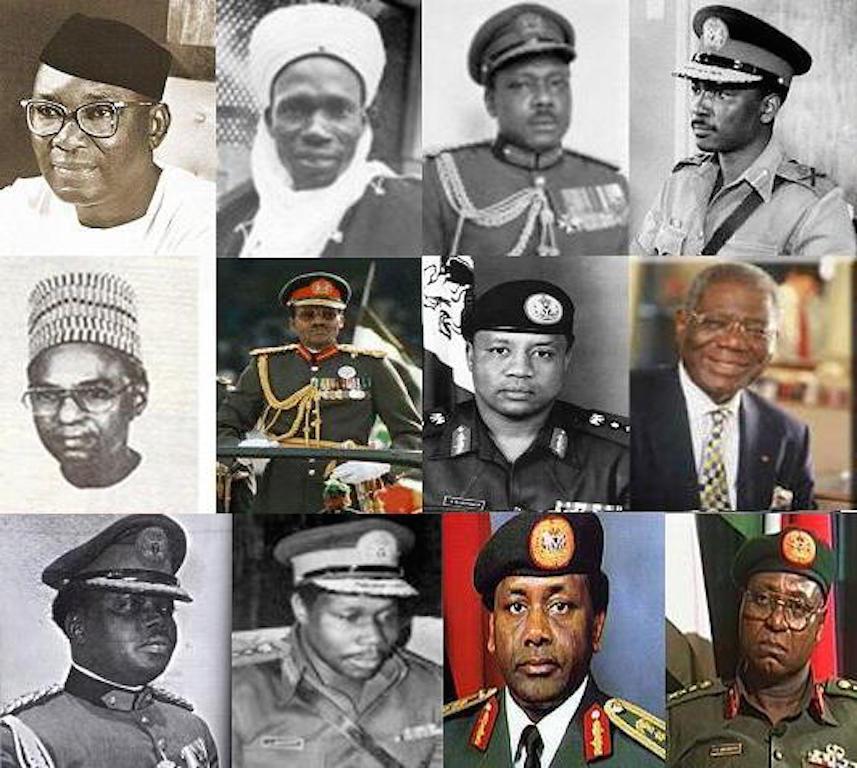

Let’s use the current and immediate past presidents of Nigeria to understand this trend.

When you look critically at much of the online conversation, one thing quickly strikes you about the young elite supporters (and by elite I mean university educated, technology enabled, conversation starters) of Goodluck Jonathan and Muhammadu Buhari – the latter is quick to admit the failings of the man they voted, while the former insists incongruously, ridiculously that their man was not just good, but one of Nigeria’s best leaders.

The argument isn’t that he was a good man. But that he was a good leader.

Wait a minute, am I living in an alternative reality?

Even a series of governors and ministers who supported Jonathan actively for their own narrow reasons, businessmen who contributed to his incumbency, and random people who worked in the villa, when you sit down with them outside of the cameras, they routinely confess without hesitation: “Jonathan was a weak leader”, “He wasn’t prepared to be president”, and “He always listened to the last person in the room who spoke to him, and had no mind of his own.”

The question for leaders is not: Was he a good man? It is not: Did he have good intentions? It is certainly not, did he do some good things? It is a more detailed question: Considering the resources that he had, and the opportunities that existed, did he achieve a basic minimum that we should be entitled to as citizens?

What are we even talking about? While he was president and many people worked with him, I routinely met his own appointees, his own employees, people benefiting from his government, who would not hesitate to confess that the man was a disappointment and an ongoing letdown as a democratic leader.

This was a man without a political philosophy, without a governing ideal, without an economic blueprint, without the basic apparent capacity for formulating ideas, principles and directions, without the presence of mind to engage complex problems in the public domain, without the integrity of consistent positions, without the pretense to an operating ideology, without the benefit of vision or hindsight and apparently no capacity for self-reflection.

Under him, we lost last swaths of Nigerian territory, lost lives and families to domestic terrorists, lost the respect of the international community, lost the ability to cooperate with nations in and outside Africa, were held hostage by corrupt politicians in cahoots with devil-may-care businessmen, and experienced widening income inequality, while he celebrated the personal expansion of wealth of one citizen, and the obscene accumulation of questionable private jets. Under him, militants walked around with the swagger of validation, and soldiers lost morale, and foreign reserves took a beating. Our foreign reserves were depleted, and our oil politics polluted.

Yes, he had admirable qualities. Of course, he had admirable qualities. Yes, he took young people seriously. He loved the creative industries and respected civil society (even though some would tell you that, it was in fact his cerebral aides who loved both the creative industries and civil society and simply nudged him to follow their lead), he allowed his ministers a free hand (more out of cluelessness than deliberate strategy, but let’s even allow it), and he made giant strides in infrastructure (that in turn made available abundant sums for misdirection, but again, let’s allow it).

But what are we even talking about? Every leader has the capacity to do some good. Was it not Sani Abacha that delivered the Petroleum Trust Fund? Was it not Ibrahim Babangida that supervised our freest and fairest election? Was it not Umaru Yar’Adua that re-established federal respect for the rule of law?

The question for leaders is not: Was he a good man? It is not: Did he have good intentions? It is certainly not, did he do some good things? It is a more detailed question: Considering the resources that he had, and the opportunities that existed, did he achieve a basic minimum that we should be entitled to as citizens?

This is even more urgent in a democracy, because in a democracy, mentally competent people voluntarily decide to run for an office based on the promise that they know what they are doing, and they can do the job.

Getting into office and complaining that ‘you didn’t know how bad it was’, ‘the forces in the country are frustrating you’, ‘the country is very complex’ is beneath contempt.

What are you even talking about? You didn’t know the country was bad when you started running for elections? You didn’t know that principalities exist around our politics and governance? You did not know that running a country or a state, or even a N100 million business is hard? You didn’t know that you must expect the worst and be prepared only for the best?

No one votes a governor or a president, or a local chairman to ‘do their best’. Or, at least, no one should. You are not voted to do ‘your best’. You are not supposed to limit us to the extent of your capacity. You are supposed to rise to the occasion. You are supposed to meet the moment. You are supposed to get the job done, period.

When they fall below that basic minimum; regardless of party affiliation, economic interest, ethnic positioning, or simply to win an argument on Twitter, we should be able to say no, hell no, and demand better, and keep demanding better, until we get better.

That is the standard to which we must hold our governments. That is the standard to which we must past governments. And that is a standard to which we must hold Muhammadu Buhari.

You should not reduce those standards to make yourself feel better. You should not reduce the standard because you don’t want to accept that your choice did not meet the occasion. You should not reduce the standards so you can win an argument on social media. You should not reduce the standard because the other person’s candidate was worse. This is not a video game. This is not a social experiment. This is the business of making people’s lives better.

If Olusegun Obasanjo failed, then he failed. If Yar’adua failed, then he did. If Jonathan failed, then he failed. Assess his failure on its merits, irrespective of whether you think his successor is doing worse. If Buhari is disappointing, then he is disappointing, irrespective of whether Jonathan was a worse disappointment.

All of them were hired by all of us to do a job, and each is to be judged on its own merit. They are not to be defended and protected simply because you like the one and you dislike the other; they are to assessed independently based on the job they were given to do, and how they did that job.

That is what we deserve. No less.

You are a citizen. You deserve a government that works. And you deserve a government that works optimally.

Whether you like these guys or not, whether you supported these guys or not, whether you feel cheated by one part of the country or not, whether you violently disagree on an issue or not, there should be a basic, common sense agreement on this: we deserve, as a people, the very best that any government has to offer. We deserve leaders worthy of the positions that they are given.

When they fall below that basic minimum; regardless of party affiliation, economic interest, ethnic positioning, or simply to win an argument on Twitter, we should be able to say no, hell no, and demand better, and keep demanding better, until we get better.

If you can’t speak up, at least shut up, and let those who are able to find their voices use it for the benefit of all of us.

Enough of this tomfoolery, please.

Chude Jideonwo is co-founder and managing partner of RED.

Office of the Citizen (OOTC) is Jideonwo’s latest essay series.

This series takes a break in the month of April. It will be concluded in the May, the month of Nigeria’s annual Democracy Day.

END

Be the first to comment