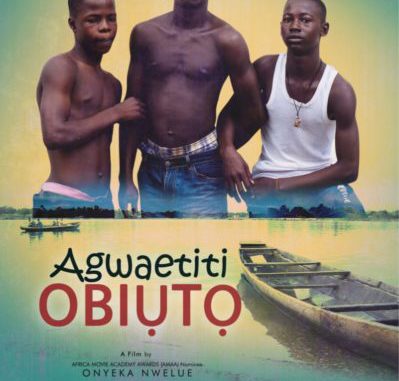

The genius in adapting a written work—in most popular forms, a novel—to screen is the unquestionable ability to bring the same creative intentions and emotional pulls to fore in the minds of viewers as contained in the original form it is adapted from. Hollywood screenwriting legend Syd Field in his book Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting defined adaptation as “finding a balance between the characters and the situation, yet keeping the integrity of the story.” Onyeka Nwelue’s Agwaetiti Obiụtọ, his first fictional feature film adapted from his novel of the same name meaning Island of Happiness, captures this essence effortlessly.

Set in Oguta, an oil-producing region in South Eastern geopolitical zone of Imo State, Nigeria, Agwaetiti Obiụtọ explores the struggles of young bloods caged by the relentless imperialist abuses of the elite, until their collective epiphany.

From its lack of basic social amenities like electricity which has lasted at least 7 years to nonfulfillment of economic pledges by multi-million dollar oil companies; direct beneficiaries and exploiters of Nigeria’s myopic, undiversified fixation with oil to obvious reasons of its financial handicap with not having any bank in the community to above all, the fatalistic unemployment of the rude and derogatory media-termed “leaders of tomorrow.”

“Oguta inspired me,” Onyeka told me when I interviewed him last week on what motivated him to make Agwaetiti Obiụtọ.

Its travails and turmoil…it is an oil producing region in Imo State in Nigeria. That is where my mother comes from. That is where Africa’s first female novelist, Flora Nwapa, comes from….The people are suffering. They are disconnected. Their suffering inspired the book, from which the film is made.

Flood disaster affects the Oguta region in September 2018. Photo Credit: Kelvin Nwaka

One of the most unique traits of iconic films is the spoken language employed. In Agwaetiti Obiụtọ, the predominant use of the Igbo language—spoken by more than 20 million people in Nigeria alone, and no thanks to the barbaric Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, spoken in both South and North Americas, the Caribbean, and other African nations like Ethiopia—one of the three major ethnic languages of oral and societal engagement in the most populous “Black” nation on earth alongside Hausa and Yoruba resonates deeply. It draws praises for its similarly pan-africanist identification symbolisms exhibiting cultural idiosyncrasies like language, lifestyle and livelihood, mirroring recent record-shattering Hollywood’s

Black Panther which rides warmly on the crest of two African languages: Nigeria’s esoteric Nsibidi and Southern Africa’s “click click” sound, Xhosa. Furthermore, by depicting the story plot in the Igbo language—a perceived symbolic representation of over 2000 African languages spoken in Motherland—Onyeka through Agwaetiti Obiụtọ reemphasises a core tool for the unification of Africa and in the same measure her emancipation from the claws of western indoctrination influenced by English, German, French, et cetera.

In the same breath, Agwaetiti Obiụtọ stays true to the dynamics of ancient African civilisation in which the highest consciousness was reserved in and with spirituality rather than religion thus insisting on the reawakening from its bastardised Judeo-Christian imitations from which their direct repercussions have been generations of docile, ignorant and indoctrinated Africans. As one of the characters would eternally note in Agwaetiti Obiụtọ, “See, if your foreign god is not working, let’s look at other options.”

Chief Priestess of Ogbuide and the Goddess of Oguta Lake, Akuzzor Anozia plays a starring role in Agwaetiti Obiụtọ. Photo Credit: Onyeka Nwelue

Agwaetiti Obiụtọ highlights deeper issues still. Oguta is a massive mine of both human and natural resources yet eternally plagued—just as other towns, regions, and cities in Nigeria, and by extension, Africa—by the whims and caprices of mental slavery, nepotism, imperialism, and an almost unrelenting, overwhelming force of subservience. In this setting, immensely gifted souls are not able to rise to the echelon of national/international relevance. For Africa to reclaim her place in the sun, she—and by this, I mean those who call her shots, or are perceived to do so—must allow her children to blossom, to glow, to become. The old must give way to the young. Power mongers must exit the stage. Chief Ogbuagu Mbanefo, epitomising the subjugating wickedness of the older generation and their economic stranglehold against the emergence of the younger generation, must be defeated.

In these struggles to combat the rapaciousness of national—and international—imperialists, Agwaetiti Obiụtọ thrives effortlessly as it forms a bond with the viewers by retaining its unwavering sense of optimism for Oguta’s (Africa’s) emancipation. As the eccentric character Bugzy would emphatically state, “ọkwa ifuru n’obodo a, anyi g’emeli” meaning “You see, we shall overcome in this town.” Yet still, the possibilities of such freedom is firmly fixed on the fact that the redemption of Oguta (Africa) is exerted through the characters of Maazi Ogbonnaya, Bugzy, Akah, Aarbenco and the defiant Ajie to lead a conscious, vigilante-like movement in checking the excesses of the crooked elite who are self-anointed to be above Law and Ethics. It is thus a story where the young must accept the responsibilities of action; of leading the charge for a much-needed change.

Even though glitches of Agwaetiti Obiụtọ’s low-production value can be sensed, the overriding relevance of its subject themes—majorly one of rape; a pun-intended ideology which devours both the natural and human resources of Oguta, even as it does the same sexually to the women who would force the hands of the revolutionary trend long overdue—the captivating charisma of its characters, original soundtracks from legendary personalities like Onyeka Onwenu, Tee Mac Iseli, Oriental Brothers, and others, give a resounding echo of pure ability to maximise limited resources, even stretch them to unprecedented heights. However, it also buttresses the need for independent film makers, especially African film makers, to be provided a healthier, creative environment; one not handicapped by finance or the mediocrity of guild directors.

On the set production of Agwaetiti Obiụtọ. Photo Credit: Onyeka Nwelue

Unsurprisingly, Agwaetiti Obiụtọ is already making waves in the international spectrum having clinched Onyeka the award for Best Director in a Feature Film at the 2018 Newark International Film Festival. It has also screened at many notable film festivals across continents including at the Africa Film Trinidad & Tobago Film Festival; Nollywood Travel Film Festival, Germany; Newark International Film Festival; Lake City Film Festival; Pearl International Film Festival; The Bioscope Cinemas, Johannesburg; The University of the Western Cape, Cape Town; Stockholm University, Sweden; Uppsala University, Sweden; and Lights, Camera, Africa Film Festival among others.

Author of the novel Island of Happiness from which the film Agwaetiti Obiụtọ—its Igbo translation—is adapted, Onyeka Nwelue.

Staying true to its relevance to the struggle for the emancipation of Africa, recognitions have followed at the same pace, or perhaps even faster. Agwaetiti Obiụtọ has been nominated in two categories for the 2018 Africa Movie Academy Awards (AMAA) holding in Kigali, Rwanda later in the month: Best First Feature Film by a Director and the Ousmane Sembere Award for Best Film in an African Language. It is my earnest anticipation in view of Agwaetiti Obiụtọ’s relevance to Africa’s struggle, that it carts away both awards and goes on to achieve greater things in the ultimate fight for Africa’s re-emergence!

To engage me on Facebook, follow @ Eleanya Ndukwe Jr.

END

Be the first to comment