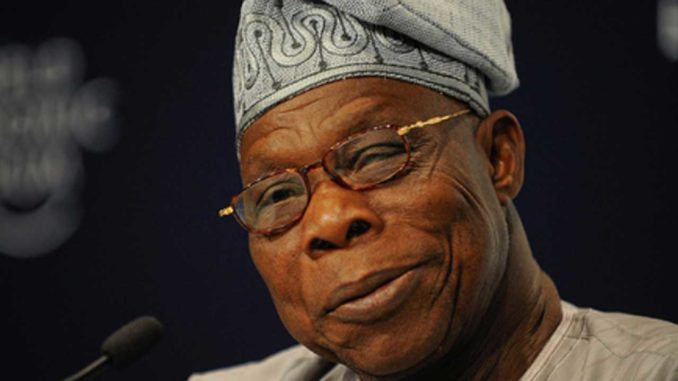

Today, Nigeria is fast drifting to a failed and badly divided state; economically, our country is becoming a basket case and poverty capital of the world, and socially, we are firming up as an unwholesome and insecure country”

– Former President Olusegun Obasanjo, The PUNCH, Monday, September 14, 2020.

Controversy has rapidly collated around former President Olusegun Obasanjo’s recent statement quoted in the opening paragraph to the effect that Nigeria is fast developing into a failed state. On the face of it, there is nothing really new or revelatory about Obasanjo’s position, except that in the context of the politics of warlords which is rampant in the country and given Obasanjo’s own predilection for hard tackles on this and other governments, his observation was bound to generate animated debate. For example, although there are issues about the scientific status of the failed states typology, it has, since 2005 when it made its debut, become a rough and ready tool for assessing the fragility and infirmity, shall we call it, of weak states. Even the Fragile States Index, which is the latest mutation of the Failed States Index for 2019 ranks Nigeria as the 14th most fragile state in the world, out of 178 countries, and the ninth most fragile in Africa.

It should be noted, however, that since the Washington-based Fund for Peace started publishing the Failed States Index, Nigeria has always been ranked in the bottom league of failed states, and this includes, for instance, the year 2007, when Obasanjo was still in power with Nigeria occupying the 17th position of the most failed states on the globe. In other words, and to the extent that the Failed States Index can be considered an explanatory model, Nigeria’s vulnerabilities are partly systemic rather than contingent. This much is evident in Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka’s statement that he considers Obasanjo as one of the architects of whatever situation Nigeria finds itself today; although he went on to say that he completely agrees with Obasanjo’s narrative, despite the fact that they are often on opposed sides of the political divide. But that is not the end of the story, Obasanjo and Soyinka, for that matter, lay the blame for Nigeria’s current mess on its helmsman, Major General Muhammadu Buhari (retd.), who stands in the dock, in this light, for mismanaging the country’s diversity and for not doing enough to reverse the decay in economic and social departments of life. Interestingly, despite their bite, the observations of the two elder statesman were not intended merely as a rebuke, but to warn that unless remedial action is taken, the country may be headed for disintegration or worse. For instance, Obasanjo did say, on that occasion, that, “I believe Nigeria is worth saving on the basis of mutuality and reciprocity, and I also believe it can be done through the process, rather than talking at each other or resorting to violence”. Unfortunately, however, Obasanjo’s critics, which include information personnel of the Buhari regime, went on the offensive by calling him ‘Divider-in-Chief’, and ignoring for the most part, his salutary therapeutic proposals.

Leaders, in an emerging democracy such as ours, must cultivate the habit of listening more than they talk; more importantly, they cannot afford the kind of mindset that dismisses criticisms in knee jerk and automatic manner, without fully inspecting their possible merits. To be sure, this columnist has often complained that, as a former President and one of the longest serving of this country, it is inappropriate for Obasanjo to engage in frontal criticisms of a sitting administration, for this tends to shift the issues away from the substance of his comments to the man Obasanjo himself. This is exactly what has happened in this instance as most commentators, especially on the government side focused almost completely on Obasanjo’s personality and track-record without saying a word about the issues he raised. Of course, this may be partly political posturing, driven by the illogic of burying germane issues under name-calling, a heated tenor and condemnatory political rhetoric. To expose this logical fallacy, which is itself, a manifestation of growing intolerance in our political culture, we can ask the question: If we grant that Obasanjo is as bad as he is being portrayed, how does that improve the lives of Nigerians who are currently tormented by rampaging inflation, soaring insecurity, fallouts of a global pandemic, the throes of an upswing in fuel and electricity prices, as well as the shambles in the education and health sectors? This is a way of noting that the uncivil tenor of the debate has neither helped matters nor given hope to Nigerians that their woes are about to end.

For some reason, a culture of enforced silence is fast descending on what used to be an active civil society, one of the magnificent pillars, once upon a time, of our democracy. From time to time, therefore, there is the need to critically inspect how much or how little those in power are fulfilling their electoral mandate and are truly attending to the problems that give Nigerians sleepless nights. Regrettably, our politics is organised in such a way that burning national issues can be easily swept under the political carpet of claiming that, because those raising them are in opposition to government, the issues are not worth attending to. So, we are coping with the perverse logic that what matters is not the merit of arguments but the coloration or political leaning of those making the comments.

Grievously, in a debate that has been more productive of heat than light, opinion has fissured along ethno-regional lines witt the Northern sociopolitical groups such as the Arewa Consultative Forum, lining up on the side of government, and Southern political and cultural groups such as Afenifere and Ohaneze Ndigbo giving automatic nods to Obasanjo’s position. Not only is this an illustration of the divisions mentioned by Obasanjo, but it also certainly points up the difficulty of meaningful dialogue in a terrain where the battles are so pitched and where the room for compromise and negotiation is almost foreclosed by the intensity of polarisation. Obviously, we cannot drift this way into the next elections hoping that somehow, things will turn out right without fundamental changes. The current party structure, even though it features two large dominant parties, is also unsatisfactory because it has transferred all the cleavages into the two contraptions and marriages of convenience called parties. That is why there is so much bickering over a Northern or Southern president and issues of political succession, three years to the 2023 elections. Clearly, therefore, we must do more than what is offered by the current constitutional review process undertaken by the National Assembly, which is also beginning to take the shape of another expensive jamboree.

There is a need for over-arching dialogues with the objective of renewing the federal bargain. More importantly, the existential issues that agitate Nigerians require vigorous and inspired tackling by government and concerned stakeholders in such a way that there will still be an attentive public to carry on the requirements of the democratic process. There is no better way of disenfranchising a people than by sentencing them to hard labour and perpetual suffering.

END

Be the first to comment