Nigeria has one of the youngest populations in the world with a median age of 18 years 7 months, which means that we are the 20th youngest out of 230 countries in the latest rankings. Yesterday’s unemployment numbers published by the National Bureau of Statistics placed the unemployment rate among Nigeria’s 15-34-year-olds at 42.5%. For the record, the total number of unemployed people was estimated to be around 23 million.

Yesterday’s report looks at the nature of and changes in rates of unemployment and underemployment and shows that the national unemployment rate was at 33.3% in Q4 2020 (up from 27.1% in Q2 2020). It gets worse when you add underemployment, which to put it simply, is those whose take-home pay cannot take them home.

It gets even worse when you factor in that of the 5.9 million Nigerians with BA/BSc/HND in the Labour Market, only 2.8 million of them are fully employed with 2.4 million of them being totally unemployed. What this says about the synergy between the educational system and the labour market and the economy isn’t flattering and the implications of this level of unemployment are even less enjoyable to consider.

Let’s not beat around the bush, a country with 23 million unemployed people will pay a heavy price in economic and social costs. These costs include lost tax revenue, drops in consumption, spending and investment, social unrest, and crime rate spikes, among other issues. Savings levels also drop as these unemployed people have to be subsidised by their families and friends who end up with reduced disposable income, thus ensuring the continuation of a vicious cycle.

There are some people who will point to, and raise questions about the impact of the Covid19 pandemic on the economy but, arguably, the actions and inactions of the government have played a much more influential role in this disaster. Before the pandemic, Nigeria’s government reacted to reduced crude oil receipts by installing a harsher taxation regimen that squeezed the economy. Even worse, Nigeria’s government embarked on a boneheaded closure of our national borders. This border closure had an outsize impact on trade, which is the second-largest employer of labour in our economy. Then as if on a death wish, the government has been strangely lenient in response to the activities of the so-called “herdsmen” who have gone on kidnapping and murdering sprees that have discouraged investment in agriculture, our largest employer of labour. This insecurity is also discouraging interstate road travel (Transport), another significant employer of labour, and one which ties both Agriculture and Trade. The existence of a hostile approach to private businesses by the federal and state governments has been another major albatross and policy responses should focus on these and other foundational restrictions in Nigeria’s Constitution, political culture, and governance methods that stifle the economy.

There is also a need to consider the effect of hysteresis which in this instance refers to how extended unemployment could eventually make people even less able to get employment due to their loss of skill, sharpness, or work experience. A change in the labour market that coincides with their extended absence from a work environment also makes employability harder to achieve. In Economics, hysteresis states that historical rates of unemployment are likely to influence the current and future rates of unemployment. This would mean that the technical and vocational education that should keep unemployed people primed for the workplace and even prepares them for better employment opportunities are very important now.

A proactive approach to managing the mental health of the unemployed by working to keep them from depression, suicide, violence, or engaging in substance abuse in their search for coping mechanisms is vital to keep the social costs of unemployment from festering even further.

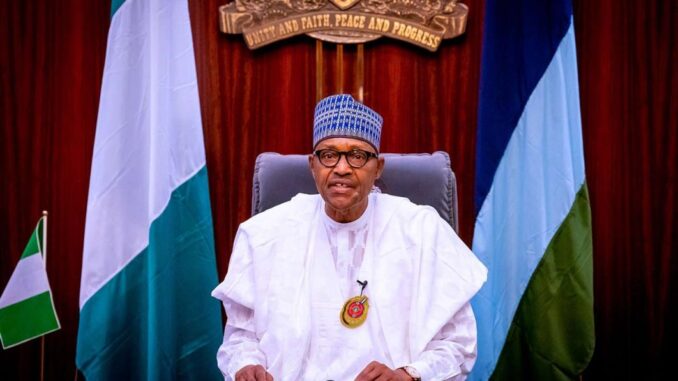

The present government came in promising “change”. While we should have been clearer on the type of change being expected, Nigeria must accept that it is time to put aside the use of disastrous statist policies and embrace a responsible strain of capital and devolved decentralised government that rewards excellence, prioritises productivity, and punishes mediocrity. The number of Nigerians who are of age and willing to work but unable to get any is something we should be very concerned about especially at a time when Nigeria is dealing with significant food inflation rises. Just as I was rounding up this piece, the NBS published the inflation numbers – 22% food inflation!

For a country in which according to research carried out by SBM Intelligence, 63% of our people spend 59% of their income on just food, that level of food inflation is murder. We have failed enough for five generations and have to do better now. The number of fully employed Nigerians in Q2 2015 was 67 million and now the figure stands at 30 million. The 37 million people who have lost jobs in the last six years are not dead. We must do something about them or we will all suffer what they are suffering.

Cheta Nwanze is a partner at SBM Intelligence

END

Be the first to comment