What’s a Nigerian citizen to do when there’s a presidential election coming up and the two leading candidates are a former dictator who’s presided over four years of lackluster growth and an alleged kleptocrat of international repute?

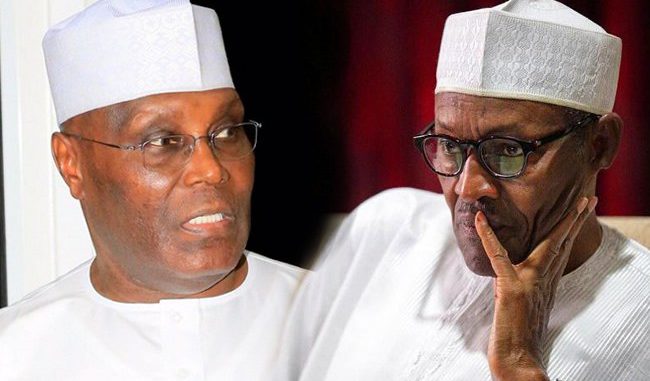

This is the choice facing Africa’s largest oil producer, and by some measures its largest economy, in the Feb. 16 vote. Although the field is crowded, incumbent Muhammadu Buhari, 76, faces his strongest challenge from Atiku Abubakar, 72, who served as vice president from 1999 to 2007 and has tried and failed several times already to secure the top job.

Buhari, who led Nigeria briefly in the 1980s as a dictator, came back to power four years ago via the ballot box. After military rule ended in 1999, he contested several elections unsuccessfully before finally becoming the first opposition figure to win the presidency. (He describes himself as a “converted democrat.”) Voters and pundits alike were optimistic that he could diversify the oil-dependent economy, tackle graft, and end Boko Haram’s deadly insurgency. While the stern former general has succeeded in stamping out some of the corruption that’s long blighted Nigeria, critics say he’s been selective, mostly targeting his political opponents. They also say he’s failed on other issues, nicknaming him “Baba Go-Slow” in reference to his age and sluggish response to crises.

Nigeria’s economy is still smaller on a per capita basis than it was in 2014, when it was hammered by the crash in crude prices. Unemployment has surged to a record 23 percent from 6.4 percent at the end of 2014. The stock market has been the world’s worst performer since Buhari came to office, falling more than 50 percent in dollar terms. Boko Haram militants, some affiliated with Islamic State, continue to wreak havoc in the northeast. Other parts of the country have been roiled by a conflict between farmers and herders that’s led to thousands of deaths.

Abubakar, widely known as Atiku, is a father of 26 who has business interests ranging from oil and gas services to food manufacturing. He’s pledged to loosen the state’s grip on the economy, end the naira’s peg to the dollar, and privatize companies including the Nigerian National Petroleum Corp., which dominates the local energy industry. But for all his market-friendly talk—he admires the late Conservative U.K. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Many Nigerians think he used his past positions in government to enrich himself.

“It’s like a choice between the devil and the deep blue sea,” says Andrew Niagwan, 36, a teacher in the central city of Jos who doesn’t know if he’ll vote. “Buhari’s got good intentions, but he doesn’t seem very capable. Our living standards have dropped in recent years. As for Atiku, Nigerians are wary because of all the allegations surrounding him.”

A U.S. Senate report in 2010 concluded that Abubakar and one of his wives had wired $40 million of “suspect funds” into American accounts and said that his business dealings “raise a host of questions about the nature and source” of his wealth. Although he has denied the claims and has never been indicted at home or abroad, Abubakar hasn’t been able to shake the perception of impropriety. In January he met with lawmakers in Washington after having been banned from the country for more than a decade under a State Department edict against politicians linked to foreign corruption, according to former U.S. officials. (A spokesperson for Abubakar’s campaign denies he’d been banned from the U.S., and the State Department declined to comment on the visit.)

Investors expect Nigerian assets to rise if Abubakar wins. “As much as Buhari has done in terms of tackling corruption, under his guidance the economy has been quite stagnant,” says Christopher Dielmann, an economist at Exotix Capital in London. “The perception is that, under Atiku, a degree of corruption could return to the country, but that might bring with it higher economic growth.”

Still, any bounce could be short-lived. Abubakar may not risk the political fallout from trying to sell state assets or, as he’s also promised, removing a cap that keeps Nigeria’s gasoline prices among the cheapest in the world.

“I’m doubtful there’d be any great change with the economy, no matter who gets elected,” says John Campbell, a former U.S. ambassador to Nigeria who’s now a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington. That’s a major problem, he says, as the United Nations projects Nigeria’s population will double, to 410 million, by 2050. “How on Earth can you grow an economy fast enough to accommodate those numbers?”

New York-based risk consultant Eurasia Group, which included Nigeria on its list of the top 10 global risks for 2019, predicts Buhari will be re-elected. But even if steadier oil prices mean the worst is over, it won’t be an easy four years. “The country might just muddle through for now,” says Amaka Anku, head of Africa at Eurasia. The next election, in 2023, could be an inflection point, she says. “There’s a real chance that a reformist government emerges then.”

BOTTOM LINE – No matter who wins Nigeria’s presidential election, the economy is unlikely to improve, setting up the nation for a humanitarian catastrophe in the coming decades.

END

Be the first to comment