When OPEC exempted Nigeria from its plan to cut oil output for the first time in eight years, it highlighted how far Africa’s biggest producer has fallen.

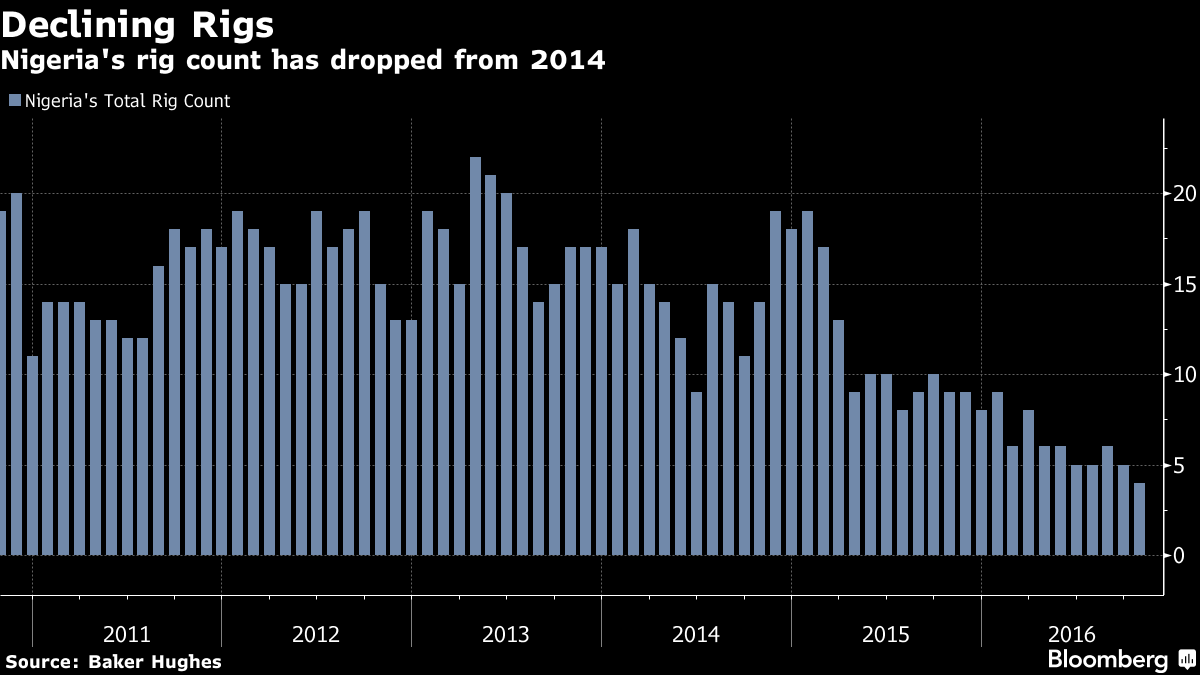

From January to October, just over three wells a month were drilled in Nigeria, down from a monthly average of almost 22 in 2006, according to petroleum ministry data. While output rebounded to 2.1 million barrels a day from the 27-year low in August, that’s just half the government’s goal at the start of the millennium.

While OPEC members try to implement a deal in Vienna next week, Nigerian lawmakers in Abuja must unblock an eight-year legislative impasse that’s seen oil majors from Royal Dutch Shell Plc to Chevron Corp. quit fields in the West African nation. To end the regulatory uncertainty, Nigeria needs to set tax rates that spur investment in a stagnating deep-water sector and address unrest that has disrupted production in the Niger Delta.

“Any business requires clarity on the operating environment before committing to investments,” said Pabina Yinkere, an energy analyst and head of research at Lagos-based Vetiva Capital Ltd. “The uncertainty surrounding the passage of the petroleum industry bill definitely stalled possibly hundreds of billions of dollars commitments on many projects.”

Since the oil bill was first sent to Nigerian lawmakers in 2008, international producers have sold at least $5.2 billion of assets to local companies. Most of those sales came before oil prices slumped in mid-2014.

Officials at Shell, Exxon Mobil Corp., Chevron, Total SA and Eni SpA declined to comment on the impact of regulatory uncertainty on their operations. Oil majors in joint ventures with state-owned Nigerian National Petroleum Corp. pump about 80 percent of the country’s oil.

Regulatory Uncertainty

The lack of clarity “was one of the main contributory factors behind divestments by Shell, Chevron and ConocoPhillips,” said Antony Goldman of London-based PM Consulting, which advises on risk in West Africa’s oil and gas industry. “No other international company, including the Chinese, were among the buyers.”

Nigeria has been granted an exemption from OPEC’s supply-management plan after output fell as low as 1.39 million barrels a day in August, following attacks by militants on oil pipelines supplying the Forcados, Qua Iboe, Brass River and Bonny export terminals. The conflict, combined with lower oil prices, has blighted the economy which is heading for its first full-year recession in 2016 since 1991, according to the International Monetary Fund.

While exacerbated by low prices and violence in the Niger Delta, the decline in the nation’s oil industry goes back more than a decade as investors reined in exploration, said Goldman. Nigeria’s crude reserves have dropped to less than 32 billion barrels from 37 billion barrels 15 years ago, and far short of a 2010 target for 40 billion barrels, according to Yinkere.

Lost Investment

Nigeria may have lost $200 billion in investment, according to the Abuja-based Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative.

Even recent discoveries, such as Exxon’s 1 billion-barrel deep-water asset last month, largely reflect old efforts paying off in a part of the Gulf of Guinea known for its prodigious prospects, said Yinkere.

President Muhammadu Buhari, who promised to end the legislative logjam after winning elections last year, has yet to present a new draft of a bill that would end squabbling among regions over the distribution of revenues.

In December, frustrated lawmakers will push a private-members bill to address oil company concerns over proposals to increase tax rates on offshore fields from 50 percent, Senate President Bukola Saraki said in a Nov. 10 interview in Abuja.

“We have to engage with the operators, hear their views and also look at Nigeria’s interest from our revenue point of view,” Saraki said. “We can’t dictate as government, a take-it-or-leave-it approach. It has to be a win-win.”

Emmanuel Kachikwu, Nigeria’s minister of state for petroleum, has said he’ll work with the Senate to ensure the reform bill is passed in the next year.

Without the law and clear “contractual terms” for operators, Nigeria won’t reverse the decline in its oil industry, according to Goldman. “In eight years the bill has gone through many forms and no one knows when that’s going to end.”

Bloomberg

END

Be the first to comment